Classical Historian curriculum is based on the Socratic Method. Using our materials, teachers and homeschoolers empower students to analyze the past. Then, they follow our guides to facilitate Socratic discussions on important events, people, and ideas. This Classical approach prepares young people to seek truth and practice wisdom.

You can learn more about classical education at the bottom of this page.

You can learn more about classical education at the bottom of this page.

Become a Socratic Teacher

Teaching the Socratic Discussion in History DVD Seminar

|

Teach American Civics

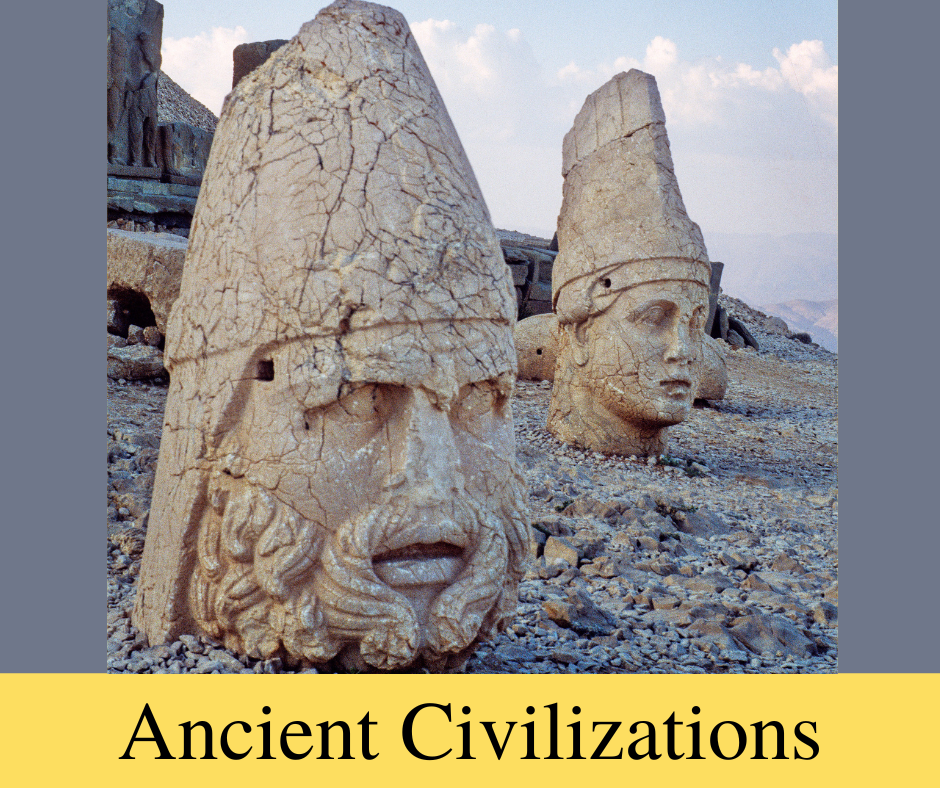

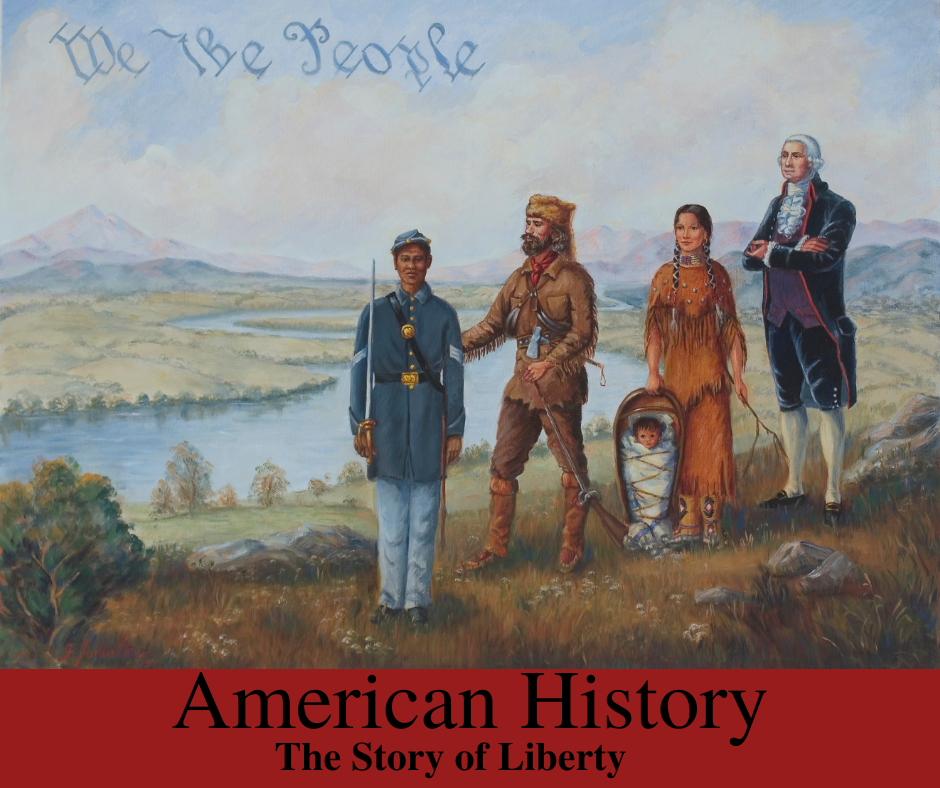

Choose Your Middle School History Curriculum

Choose Your High School History Curriculum

We offer two options for both our World History and American History curricula.

See the dates below the images to find the right materials for your students.

See the dates below the images to find the right materials for your students.

Running a Classical School or Co-op? Click here.

America Needs Classical Education

As one of my colleagues at the public school said, “We all know our students are going to be working in factories or outside doing menial tasks. Our job is to teach them organizational skills.”

In K-12, undergraduate, and graduate-level education, history classrooms are often places of indoctrination. Students are compelled to learn what the teacher thinks and they are taught how to convey this message to others. And because most teachers and professors in the United States rely on government support for their paycheck, it is only natural that most educators support a larger and more powerful state.

More tax money coming into state-run and state-subsidized schools translates to higher salaries and better working conditions for teachers. The result? An educational system biased towards a more powerful government. Students cannot be expected to learn how to analyze the past logically if their schools have been corrupted by financial incentives.

Along with the ideological problems, many classrooms are structured to teach large groups of students menial tasks or "job skills" such as organization, memorization, and emotional regulation. Teachers who feel overwhelmed by so much non-academic work and whose students are unable to perform simple reading, writing, and speaking tasks, eventually succumb to the belief that their students will never be able to work in linguistically rich environments. As one of my colleagues at the middle school said, “We all know our students are going to be working in factories or outside doing menial tasks. Our job is to teach them organizational skills.”

No wonder that 54% of Americans cannot read past the sixth-grade level!

More tax money coming into state-run and state-subsidized schools translates to higher salaries and better working conditions for teachers. The result? An educational system biased towards a more powerful government. Students cannot be expected to learn how to analyze the past logically if their schools have been corrupted by financial incentives.

Along with the ideological problems, many classrooms are structured to teach large groups of students menial tasks or "job skills" such as organization, memorization, and emotional regulation. Teachers who feel overwhelmed by so much non-academic work and whose students are unable to perform simple reading, writing, and speaking tasks, eventually succumb to the belief that their students will never be able to work in linguistically rich environments. As one of my colleagues at the middle school said, “We all know our students are going to be working in factories or outside doing menial tasks. Our job is to teach them organizational skills.”

No wonder that 54% of Americans cannot read past the sixth-grade level!

Classical Education vs. Progressive Education

It wasn't always like this. In fact, before the public school system was created, Americans had the highest complex literacy rate in the world. They achieved this noteworthy success because they wanted their children to understand the Bible and participate in self-government. "Job skills" had nothing to do with it — after all, yeomen farmers don't need complex literacy to survive.

What changed? Well, the classical model practiced by early Americans — and indeed, by all educated Westerners — was replaced by progressive education in the early 1900s. Progressives believed it to be more important to train students how to work in an industrialized country than how to be good thinkers.

John Dewey (1859-1952), the main proponent of progressive education, emphasized “learning by doing” and rejected memorization and classical language study. As N.S. Lyons writes, "Dewey believed public education was 'the fundamental method of social progress and reform' precisely because it was, he wrote, 'the only sure method of social reconstruction.'"

Progressives like Dewey corrupted schools, turning them from places of education to revolutionary experiments. We see the results all around us. Today's students graduate from both K-12 schools and universities without having learned anything about their own heritage. Left without a foundation, they make easy prey for radical ideologies. Tragically, many end up anxious, confused, and depressed.

But there is a silver lining: millions of Americans are waking up. They believe that school should not be a place of social experimentation. Instead, they've adopted the classical view: schools should focus on education and character formation. What a radical idea!

What changed? Well, the classical model practiced by early Americans — and indeed, by all educated Westerners — was replaced by progressive education in the early 1900s. Progressives believed it to be more important to train students how to work in an industrialized country than how to be good thinkers.

John Dewey (1859-1952), the main proponent of progressive education, emphasized “learning by doing” and rejected memorization and classical language study. As N.S. Lyons writes, "Dewey believed public education was 'the fundamental method of social progress and reform' precisely because it was, he wrote, 'the only sure method of social reconstruction.'"

Progressives like Dewey corrupted schools, turning them from places of education to revolutionary experiments. We see the results all around us. Today's students graduate from both K-12 schools and universities without having learned anything about their own heritage. Left without a foundation, they make easy prey for radical ideologies. Tragically, many end up anxious, confused, and depressed.

But there is a silver lining: millions of Americans are waking up. They believe that school should not be a place of social experimentation. Instead, they've adopted the classical view: schools should focus on education and character formation. What a radical idea!

Classical Education: Process Over Content

But what is classical education? The best way to think about classical education is that it is not focused on content, but on a process. Put simply, classical education equips students to research and analyze information independently as they seek the truth. The question is not simply what a student should learn, but how they should learn it.

This is especially true of history. History is often taught as a single narrative that students simply consume. Someone else has already researched and analyzed the evidence for them. All they must do is read their textbooks and pass their tests.

Our classical history curriculum is different. Instead of teaching students what to think, it teaches them how to be historians. In other words, it teaches them how to research, analyze evidence, evaluate competing sources, and develop a persuasive argument about the past.

This approach is Socratic because it is driven by questions. Instead of passing down a narrative, we challenge students to take a stand on an open-ended issue. Then, they have to defend their position in a Socratic discussion. After discussing with classmates, teachers, or homeschool parents, students write a persuasive essay.

This is especially true of history. History is often taught as a single narrative that students simply consume. Someone else has already researched and analyzed the evidence for them. All they must do is read their textbooks and pass their tests.

Our classical history curriculum is different. Instead of teaching students what to think, it teaches them how to be historians. In other words, it teaches them how to research, analyze evidence, evaluate competing sources, and develop a persuasive argument about the past.

This approach is Socratic because it is driven by questions. Instead of passing down a narrative, we challenge students to take a stand on an open-ended issue. Then, they have to defend their position in a Socratic discussion. After discussing with classmates, teachers, or homeschool parents, students write a persuasive essay.

A Socratic Approach to the Liberal Arts

The Socratic discussion is an integral element of a Classical Education. In a Socratic discussion, students present their position on an open-ended question and defend it with evidence and logic.

Needless to say, the Socratic discussion can be applied to more than history. In our government and economics textbook, for example, students learn about the Constitution and the market economy using the same Socratic approach as our history books. Similarly, in our online literature classes, students participate in Socratic discussions about great books.

This is why we emphasize that classical education is a process. It prepares students to make sense of the world around them. If it only told them what to think, they would be unprepared to research and analyze information on their own. By teaching them how to think, we cultivate the next generation of American leaders.

Needless to say, the Socratic discussion can be applied to more than history. In our government and economics textbook, for example, students learn about the Constitution and the market economy using the same Socratic approach as our history books. Similarly, in our online literature classes, students participate in Socratic discussions about great books.

This is why we emphasize that classical education is a process. It prepares students to make sense of the world around them. If it only told them what to think, they would be unprepared to research and analyze information on their own. By teaching them how to think, we cultivate the next generation of American leaders.

Classical Education: An Age-Appropriate Philosophy

Dorothy Sayers was a twentieth-century English writer who spearheaded the revival of the Socratic approach to education. She wrote in “The Lost Tools of Learning” that students need to learn the analytical tools of learning before they learn a variety of “subjects.” She separated a student’s life into three stages:

The Grammar stage is appropriate to the child before the age of 11 or 12. Sayers called this stage the “Poll Parrot” because the child is so intent at pleasing his parent that he will parrot whatever the parent teaches him. In the Grammar Stage, children read interesting stories, memorize simple facts, and learn geography. We think the best way to achieve those goals is through history games.

Near the age of 12 or so, when a child begins to express his own thoughts and seems to want to argue intellectually, he has entered the Dialectic or Logic stage. In this stage, the student is capable of acquiring and using the tools of learning. In the study of history, these tools include but are not limited to the following:

In the final stage, Rhetoric, the student continues to use the tools of learning and works on perfecting his ability to speak and write. The student in the Rhetoric stage should be given more primary source materials to read and analyze and spend less time working with a textbook.

Primary source materials are those created by the eyewitness to history. For example, the journal of Christopher Columbus is a primary source, whereas the history textbook in a classroom a secondary source. The student should be introduced to the greatest thinkers and writers of all time and discuss their ideas.

- Grammar

- Dialectic

- Rhetoric

The Grammar stage is appropriate to the child before the age of 11 or 12. Sayers called this stage the “Poll Parrot” because the child is so intent at pleasing his parent that he will parrot whatever the parent teaches him. In the Grammar Stage, children read interesting stories, memorize simple facts, and learn geography. We think the best way to achieve those goals is through history games.

Near the age of 12 or so, when a child begins to express his own thoughts and seems to want to argue intellectually, he has entered the Dialectic or Logic stage. In this stage, the student is capable of acquiring and using the tools of learning. In the study of history, these tools include but are not limited to the following:

- distinguishing fact from opinion

- developing good judgment from historical evidence

- critiquing various historical sources

- understanding the various influences on history

- participating in the Socratic discussion

- writing analytical essays

In the final stage, Rhetoric, the student continues to use the tools of learning and works on perfecting his ability to speak and write. The student in the Rhetoric stage should be given more primary source materials to read and analyze and spend less time working with a textbook.

Primary source materials are those created by the eyewitness to history. For example, the journal of Christopher Columbus is a primary source, whereas the history textbook in a classroom a secondary source. The student should be introduced to the greatest thinkers and writers of all time and discuss their ideas.

The Absolute in History Education

The Absolute is the concept of an unconditional reality, existing regardless of individual circumstances. In simpler terms - for the study of history, this idea means that there is a truth; students and teachers are called to honestly search for the truth, and all work in history needs to be aimed at discovering the truth.

Without the existence of the Absolute, any definition of human nature, of what is right and worthwhile, becomes relative. The tragedies caused by mass murderers like Mao and Hitler and Stalin become merely decisions and outcomes taken by others instead of horrendous acts. Without the goal of searching for the truth in history, the classroom becomes slave to the bias of the teacher as he attempts to shape students into what he has determined what is good or bad.

In a public school district-sponsored Common Core Training I attended in 2013, the presenter stated that everything in history is up to debate and that there is not one right answer. When I challenged her by giving examples of the mass murders ordered by Stalin, Hitler, and Mao, she changed the subject. Without the idea that there is an Absolute, mass murders, torture, and other indignations become merely sad, not wrong.

As the philosopher Hannah Arendt, a German Jew who escaped the Nazis, said, “The ideal subject of totalitarian rule is not the convinced Nazi or the convinced Communist, but people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction (i.e., the reality of experience) and the distinction between the true and the false (i.e., the standards of thought) no longer exist.”

America’s educational establishment would like to erase the concept of truth because people who do not believe in truth can be more easily manipulated. We owe it to our children and ourselves to offer alternatives based in truth, goodness, and beauty.

Without the idea of an Absolute, the study of history becomes an intellectual distraction at best, and a tool of indoctrination at worst. Studying history goes beyond the mere memorization of certain facts. It is the search for true causes, effects, reasons, and ideas.

Without the existence of the Absolute, any definition of human nature, of what is right and worthwhile, becomes relative. The tragedies caused by mass murderers like Mao and Hitler and Stalin become merely decisions and outcomes taken by others instead of horrendous acts. Without the goal of searching for the truth in history, the classroom becomes slave to the bias of the teacher as he attempts to shape students into what he has determined what is good or bad.

In a public school district-sponsored Common Core Training I attended in 2013, the presenter stated that everything in history is up to debate and that there is not one right answer. When I challenged her by giving examples of the mass murders ordered by Stalin, Hitler, and Mao, she changed the subject. Without the idea that there is an Absolute, mass murders, torture, and other indignations become merely sad, not wrong.

As the philosopher Hannah Arendt, a German Jew who escaped the Nazis, said, “The ideal subject of totalitarian rule is not the convinced Nazi or the convinced Communist, but people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction (i.e., the reality of experience) and the distinction between the true and the false (i.e., the standards of thought) no longer exist.”

America’s educational establishment would like to erase the concept of truth because people who do not believe in truth can be more easily manipulated. We owe it to our children and ourselves to offer alternatives based in truth, goodness, and beauty.

Without the idea of an Absolute, the study of history becomes an intellectual distraction at best, and a tool of indoctrination at worst. Studying history goes beyond the mere memorization of certain facts. It is the search for true causes, effects, reasons, and ideas.

Our Traditional Historical Perspective

Like all people, we have a bias, or perspective, on history. Because our classical curriculum is focused on critical thinking, our perspective does not influence our materials as much as it would if we were focused on content. That being said, we want to be completely honest about our perspective.

We have a traditional history perspective. Rather than seeing the classroom as a site for reshaping society, we want students to graduate with a sense of who they are and where they come from. This means that we introduce them to the great ideas and traditions of Western Civilization. We uphold the values of goodness, truth, and beauty, and respect the religious beliefs of our parents and students. Finally, we champion the American heritage of self-government and the rule of law. To read more about our values, click here.

We have a traditional history perspective. Rather than seeing the classroom as a site for reshaping society, we want students to graduate with a sense of who they are and where they come from. This means that we introduce them to the great ideas and traditions of Western Civilization. We uphold the values of goodness, truth, and beauty, and respect the religious beliefs of our parents and students. Finally, we champion the American heritage of self-government and the rule of law. To read more about our values, click here.

|

SUPPORT

|

RESOURCES

|

|