- Store

- >

- American History, Columbus to 1914

- >

- The Story of Liberty, America's Ancient Heritage through the Civil War Bundle

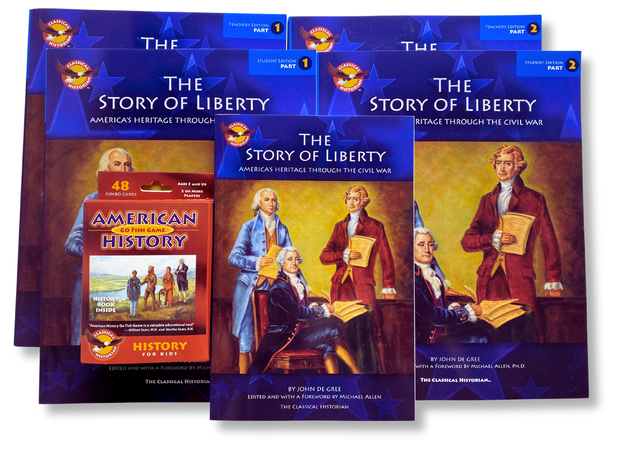

The Story of Liberty, America's Ancient Heritage through the Civil War Bundle

SKU:

304

$139.94

$125.95

$125.95

On Sale

Unavailable

per item

This comes complete with everything you need to teach middle school American History with the Socratic Method.

If this is your first year teaching with us, we recommend starting with our teaching training course, Teaching the Socratic Discussion in History DVD Seminar.

We also offer recorded Socratic discussions from this curriculum in The Dolphin Society.

HOW DOES IT WORK? |

|

-

Bundle Contents

-

The Story of Liberty

-

Supplemental

-

Individual Materials

-

Reviews

<

>

Comprehensive Middle School US History Curriculum

- The Story of Liberty, Textbook (ISBN 9780692887578)

- Workbooks, Student Editions, Parts 1 (ISBN 9781732073807) and 2 (ISBN 9781732073814)

- Workbooks, Teacher Editions, Parts 1 (ISBN 9781732073821) and 2 (ISBN 9781732073821)

- American History Go Fish

- Primary Sources (Free on this website - to access them, go to the footer.)

Here are samples taken from Teacher's Edition 1:

| unit_1_final.pdf | |

| File Size: | 8947 kb |

| File Type: | |

| Unit 6 Teacher Edition Workbook.pdf | |

| File Size: | 9861 kb |

| File Type: | |

American History and the Story of Liberty

Classical Historian is devoted to telling the story of liberty. This story is as old as the human race, but for most people in the past as well as today, liberty has remained out of reach. This is a great tragedy, for people cannot reach their full potential unless they are free.

The American Founding Fathers hoped to preserve liberty by limiting government. In the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson wrote that the purpose of government is to protect inalienable rights including “Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.” In the Constitution, the Founders bound the government with laws that would uphold the rights of citizens. The American experience has been exceptional largely because the American government has been bound by law.

Many modern Americans do not know the history of their own country, so they cannot understand the significance of the founding of the United States. Many modern Americans classrooms don’t have a single civics textbook, so students have no chance to appreciate the history of liberty. Classical Historian is committed to changing that.

The American Founding Fathers hoped to preserve liberty by limiting government. In the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson wrote that the purpose of government is to protect inalienable rights including “Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.” In the Constitution, the Founders bound the government with laws that would uphold the rights of citizens. The American experience has been exceptional largely because the American government has been bound by law.

Many modern Americans do not know the history of their own country, so they cannot understand the significance of the founding of the United States. Many modern Americans classrooms don’t have a single civics textbook, so students have no chance to appreciate the history of liberty. Classical Historian is committed to changing that.

The Ancient Roots of Liberty

The story of liberty is the story of Western Civilization. It begins with early man, develops over the centuries, and in many ways, it comes to fruition with the birth of America. In ancient times, most people believed in many gods, leaders imposed unfair laws on their subjects, and life was short and miserable for those without power. Unfortunately, this remains the case in some places today. However, about 4,000 years ago, the Hebrews believed in one God, in justice, and in morality, regardless of the circumstance of one’s birth.

Then, around 2,500 years ago, the ancient Athenians created democracy, the idea that citizens had the right to vote for their leaders and laws, instead of being subject to a king. At about the same time, the Romans established a republic. Citizens had rights the government had to respect. As the Roman Republic expanded, the liberties of its citizens shrank. In 27 B.C., the Roman Empire arose and the rights people had under the Roman Republic greatly diminished.

However, within the Roman Empire, Jesus Christ established a new religious belief where God loved everyone equally. For the first time in history, a religion offered salvation to all people, not just people of a certain nationality or tribe. This religious understanding of equality under God was transformed over time into the idea that all people should be treated the same by the law. And thus, Thomas Jefferson wrote, “all men are created equal.”

Then, around 2,500 years ago, the ancient Athenians created democracy, the idea that citizens had the right to vote for their leaders and laws, instead of being subject to a king. At about the same time, the Romans established a republic. Citizens had rights the government had to respect. As the Roman Republic expanded, the liberties of its citizens shrank. In 27 B.C., the Roman Empire arose and the rights people had under the Roman Republic greatly diminished.

However, within the Roman Empire, Jesus Christ established a new religious belief where God loved everyone equally. For the first time in history, a religion offered salvation to all people, not just people of a certain nationality or tribe. This religious understanding of equality under God was transformed over time into the idea that all people should be treated the same by the law. And thus, Thomas Jefferson wrote, “all men are created equal.”

Liberty and America

The story of liberty in America has not been a perfect one. From 1776 to 1865, slavery was legal in half of the country. How could a person have liberty if he were owned by another person? In addition, women were not allowed to vote and did not have the same property rights as men.

From 1861–1865, Americans fought their greatest war, the Civil War, which resolved the contradiction between liberty and slavery. Though it took 89 years, the rights Jefferson spoke about in the Declaration of Independence finally did spread to all men, black and white. In addition, throughout the 1800s and early 1900s, the political rights of women expanded to be equal with men. However, liberty in America is still not perfect. It remains an ideal that Americans strive for.

This history book for middle school tells the story of liberty as it relates to American history. It traces the influence of ancient and medieval civilizations on the establishment and development of the United States of America through the Civil War. It is written with the hope that young Americans will appreciate the unique role that America has played in the drama of human liberty. It is these young people who are called to further the cause of liberty within our country and throughout the world.

From 1861–1865, Americans fought their greatest war, the Civil War, which resolved the contradiction between liberty and slavery. Though it took 89 years, the rights Jefferson spoke about in the Declaration of Independence finally did spread to all men, black and white. In addition, throughout the 1800s and early 1900s, the political rights of women expanded to be equal with men. However, liberty in America is still not perfect. It remains an ideal that Americans strive for.

This history book for middle school tells the story of liberty as it relates to American history. It traces the influence of ancient and medieval civilizations on the establishment and development of the United States of America through the Civil War. It is written with the hope that young Americans will appreciate the unique role that America has played in the drama of human liberty. It is these young people who are called to further the cause of liberty within our country and throughout the world.

Teaching Students To Be Historians

This middle school history curriculum comes with workbooks that train students how to think, speak, and write like a historian. At the beginning of the year, students learn history content and the tools of the historian sequentially. After acquiring the necessary skills, they then complete research in their text and from our online primary source documents. Next, they use their research to develop an argument in response to a Socratic discussion question. After discussing with their classmates, they write a persuasive history essay.

Table of Contents

Preface, by Michael Allen, Ph.D., University of Washington, Tacoma

Introduction

Unit One America’s Ancient Heritage

Introduction

1. The Fertile Crescent

2. The Greeks

3. The Roman Republic

4. Western Civilization

Unit Two America’s Medieval Heritage

Introduction

5. The Age of Barbarians

6. Civilizing Europe

7. Foundation of European Kingdoms

8. Development of Liberty in Medieval England

9. The Crusades

10. The Age of Exploration and Christopher Columbus

11. The Reformation and the Enlightenment

Unit 3 European Colonization of America

Introduction

12. Native Americans

13. Spanish and French Colonies in America

14. Founding of American Exceptionalism: Jamestown and Plymouth Plantation

15. American Exceptionalism Takes Hold in the English Colonies

16. Life in the English Colonies

17. Southern Colonies

18. New England Colonies

19. The Middle Colonies

20. Early Indian Wars

Unit IV Founding of the U.S.A.

Introduction

21. Early Causes of the American Revolution

22. Land Regulation, Taxes, and Conflict

23. Moving Toward War

24. The Beginning of the American Revolution

25. The Declaration of Independence

26. Defeat, Surprise, and Survival

27. The Articles of Confederation, 1777-1789

Unit V The Constitution

Introduction

28. The Making of the American Constitution

29. Principles of the Constitution

30. Individual Rights

Unit VI Era of the Founding Fathers, 1787-1825

Introduction

31. Ratification of the Constitution

32. The American People

33. Father of the Country

34. Presidency of John Adams (1797-1801)

35. The Supreme Court, Judicial Review, and Capitalism

36. Presidency of Thomas Jefferson (1801-1809)

37. Presidency of James Madison (1809-1817)

38. The Era of Good Feelings

39. American Spirit and Industry in the Free North

40. Railroads, the Post Office, and the Politicization of News

41. The Missouri Compromise

Unit VII The Beginning of Big Government, 1825-1836

Introduction

42. The Election of 1824 and the Presidency of John Quincy Adams

43. The Age of Jackson (1828-1835)

Unit VIII Empire of Liberty or Manifest Destiny, 1836-1848

Introduction

44. Change in America: Industrialization, Religion, and Social Change

45. Education in Early America through the Civil War

46. The Southwest and the War for Texas Independence (1835-1836)

47. Presidencies of Martin Van Buren (1837-1841), William Harrison (1841), and John Tyler (1841-1845)

48. Presidency of James K. Polk (1845-1849) and the Mexican-American War (1846-1848)

49. The California Gold Rush and the Oregon Trail

Unit IX Sectionalism

Introduction

50. The South

51. The North

52. Life in the West

53. Immigration

Unit X The Slavery Crisis Becomes Violent, 1848-1860

Introduction

54. Political Instability and the End of Westward Expansion

55. The Decade Preceding the Civil War

56. Abraham Lincoln

Unit XI The Civil War

Introduction

57. The Election of 1860

58. Secession and the Confederate States of America

59. Fort Sumter and the War on Paper

60. Bull Run and the Beginning of the War

61. Growth of Government

62. The Emancipation Proclamation

63. Hard War

64. Unconditional Surrender Grant and Lincoln’s Reelection

65. The End of the War and the Assassination of Abraham Lincoln

66. Winners, Losers and Lasting Changes

Introduction

Unit One America’s Ancient Heritage

Introduction

1. The Fertile Crescent

2. The Greeks

3. The Roman Republic

4. Western Civilization

Unit Two America’s Medieval Heritage

Introduction

5. The Age of Barbarians

6. Civilizing Europe

7. Foundation of European Kingdoms

8. Development of Liberty in Medieval England

9. The Crusades

10. The Age of Exploration and Christopher Columbus

11. The Reformation and the Enlightenment

Unit 3 European Colonization of America

Introduction

12. Native Americans

13. Spanish and French Colonies in America

14. Founding of American Exceptionalism: Jamestown and Plymouth Plantation

15. American Exceptionalism Takes Hold in the English Colonies

16. Life in the English Colonies

17. Southern Colonies

18. New England Colonies

19. The Middle Colonies

20. Early Indian Wars

Unit IV Founding of the U.S.A.

Introduction

21. Early Causes of the American Revolution

22. Land Regulation, Taxes, and Conflict

23. Moving Toward War

24. The Beginning of the American Revolution

25. The Declaration of Independence

26. Defeat, Surprise, and Survival

27. The Articles of Confederation, 1777-1789

Unit V The Constitution

Introduction

28. The Making of the American Constitution

29. Principles of the Constitution

30. Individual Rights

Unit VI Era of the Founding Fathers, 1787-1825

Introduction

31. Ratification of the Constitution

32. The American People

33. Father of the Country

34. Presidency of John Adams (1797-1801)

35. The Supreme Court, Judicial Review, and Capitalism

36. Presidency of Thomas Jefferson (1801-1809)

37. Presidency of James Madison (1809-1817)

38. The Era of Good Feelings

39. American Spirit and Industry in the Free North

40. Railroads, the Post Office, and the Politicization of News

41. The Missouri Compromise

Unit VII The Beginning of Big Government, 1825-1836

Introduction

42. The Election of 1824 and the Presidency of John Quincy Adams

43. The Age of Jackson (1828-1835)

Unit VIII Empire of Liberty or Manifest Destiny, 1836-1848

Introduction

44. Change in America: Industrialization, Religion, and Social Change

45. Education in Early America through the Civil War

46. The Southwest and the War for Texas Independence (1835-1836)

47. Presidencies of Martin Van Buren (1837-1841), William Harrison (1841), and John Tyler (1841-1845)

48. Presidency of James K. Polk (1845-1849) and the Mexican-American War (1846-1848)

49. The California Gold Rush and the Oregon Trail

Unit IX Sectionalism

Introduction

50. The South

51. The North

52. Life in the West

53. Immigration

Unit X The Slavery Crisis Becomes Violent, 1848-1860

Introduction

54. Political Instability and the End of Westward Expansion

55. The Decade Preceding the Civil War

56. Abraham Lincoln

Unit XI The Civil War

Introduction

57. The Election of 1860

58. Secession and the Confederate States of America

59. Fort Sumter and the War on Paper

60. Bull Run and the Beginning of the War

61. Growth of Government

62. The Emancipation Proclamation

63. Hard War

64. Unconditional Surrender Grant and Lincoln’s Reelection

65. The End of the War and the Assassination of Abraham Lincoln

66. Winners, Losers and Lasting Changes

Preface

Young American history students and their teachers have long yearned for a book like the one you now hold in your hands. John De Gree’sThe Story of Liberty, From America’s Heritage through the Civil War, is a well-researched, ably-written, and sensible depiction of American history from the founding through the Civil War. What do I mean by “sensible”? Simply this: John relates the truth about the American past by telling about our many good qualities and accomplishments as well as the setbacks our nation has endured during its long history. Few books as good as this one have been published for young readers. At last we have a new, up-to-date book suitable for American middle school and high school history students.

When Larry Schweikart and I first published our #1 New York Times best-selling book, A Patriot’s History of the United States, we succeeded in filling a similar void existing in college-level American history books. Larry and I have often said that American history is not the story of, to use an old folk saying, a “half-empty cup.” Indeed, we argued that the American cup was nearly full. Americans have made great mistakes, but they have also done much that is good. American patriots in 1776 created a democratic republic governed by ordinary citizens at a time in history when absolutist monarchs ruled most of Europe, all-powerful Czars, Emperors, and Shoguns tyrannized Russia and the Far East, and some Middle Eastern and North African monarchs claimed divine authority and direct links to God. While it is true that Americans allowed the enslavement of African-American people, they ultimately fought a bloody war that ended slavery forever. While American soldiers killed native Indians and pushed them westward onto reservations, American diplomats signed legally binding treaties that those Indians’ descendants use to their great benefit in courts today. And while there has been poverty and suffering in our country’s history, it pales in comparison to that of the rest of the world. It is no accident that, for over 400 years, millions of foreigners have yearned and sought to become Americans.

John De Gree tells about this and much more in The Story of Liberty, From America’s Heritage through the Civil War. He traces our nation’s past from the time of the Pilgrims through the Colonial era and the American Revolution. He explains Jeffersonian and Jacksonian politics and the critical events leading to the Civil War. And he narrates the military and political history of that pivotal conflict. John has a unique way of telling the story of the United States. He places special emphasis on America’s place in the history of advancing Western Civilization. He begins with our classical roots and ties to ancient Hebrew, Greek, Roman, and Western European institutions. Just as importantly, he accurately weaves the story of Christianity and Christian values into the American story. No truthful history of the United States of America can ignore this vital religious element.

I first met John De Gree nearly a decade ago when we collaborated on curriculum for the growing number of homeschool, charter, private, and public school students who utilize his Classical Historian method. I remain impressed with his intellect and work ethic, and the range of exciting, effective tools he offers modern students of American history and their teachers. I am confident The Story of Liberty, From America’s Heritage through the Civil War, will become a very successful textbook in educating a future generation of American patriots.

When Larry Schweikart and I first published our #1 New York Times best-selling book, A Patriot’s History of the United States, we succeeded in filling a similar void existing in college-level American history books. Larry and I have often said that American history is not the story of, to use an old folk saying, a “half-empty cup.” Indeed, we argued that the American cup was nearly full. Americans have made great mistakes, but they have also done much that is good. American patriots in 1776 created a democratic republic governed by ordinary citizens at a time in history when absolutist monarchs ruled most of Europe, all-powerful Czars, Emperors, and Shoguns tyrannized Russia and the Far East, and some Middle Eastern and North African monarchs claimed divine authority and direct links to God. While it is true that Americans allowed the enslavement of African-American people, they ultimately fought a bloody war that ended slavery forever. While American soldiers killed native Indians and pushed them westward onto reservations, American diplomats signed legally binding treaties that those Indians’ descendants use to their great benefit in courts today. And while there has been poverty and suffering in our country’s history, it pales in comparison to that of the rest of the world. It is no accident that, for over 400 years, millions of foreigners have yearned and sought to become Americans.

John De Gree tells about this and much more in The Story of Liberty, From America’s Heritage through the Civil War. He traces our nation’s past from the time of the Pilgrims through the Colonial era and the American Revolution. He explains Jeffersonian and Jacksonian politics and the critical events leading to the Civil War. And he narrates the military and political history of that pivotal conflict. John has a unique way of telling the story of the United States. He places special emphasis on America’s place in the history of advancing Western Civilization. He begins with our classical roots and ties to ancient Hebrew, Greek, Roman, and Western European institutions. Just as importantly, he accurately weaves the story of Christianity and Christian values into the American story. No truthful history of the United States of America can ignore this vital religious element.

I first met John De Gree nearly a decade ago when we collaborated on curriculum for the growing number of homeschool, charter, private, and public school students who utilize his Classical Historian method. I remain impressed with his intellect and work ethic, and the range of exciting, effective tools he offers modern students of American history and their teachers. I am confident The Story of Liberty, From America’s Heritage through the Civil War, will become a very successful textbook in educating a future generation of American patriots.

More than 1 student? For The Story of Liberty Student Bundle click here.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE:

As Reviewed by the Authors of A Patriot's History of the US

In John DeGree's The Story of Liberty, written for ages 11 to young adults, America's foundations are traced from the Hebrews and the Judeo-Christian religious traditions to the Greco-Roman political traditions to the establishment of government in the English colonies in America. The Story of Liberty highlights---often with primary source documents such as the "Mayflower Compact" the first Thanksgiving Declaration, a section from the account of Paul Revere's ride---fleshes out the narration with easily-readable charts on such things as the differences between Republicans and Federalists or the size of early American cities.The book ends with Lincoln's assassination, and a second volume from 1865 to the present is planned. Loosely based on A Patriot's History of the United States by myself and Michael Allen (who did the foreword), The Story of Liberty strongly integrates the timeless principles of the sanctity of life, freedom of choice, government by representatives, trial by jury, division of power in government, and more. Strongly recommended. —Larry Schweikart, Ph.D.

Larry Schweikart, Ph.D., is co-author of #1 NY Times bestseller, A Patriot’s History of the United States of America, numerous top selling history books, and is a film producer of history documentaries.

John De Gree has a unique way of telling the story of the United States. He places special emphasis on America’s place in the history of advancing Western Civilization. He begins with our classical roots and ties to ancient Hebrew, Greek, Roman, and Western European institutions. Just as importantly, he accurately weaves the story of Christianity and Christian values into the American story… John relates the truth about the American past by telling about our many good qualities and accomplishments as well as the setbacks our nation has endured during its long history…Young American history students and their teachers have long yearned for a book like the one you now hold in your hands. —Michael Allen, Ph.D.

Michael Allen, Ph.D., co-author of the #1 New York Times best-selling book, A Patriot’s History of the United States. Professor at the University of Washington, Tacoma and Editor of The Story of Liberty, America's Heritage Through the Civil War

Larry Schweikart, Ph.D., is co-author of #1 NY Times bestseller, A Patriot’s History of the United States of America, numerous top selling history books, and is a film producer of history documentaries.

John De Gree has a unique way of telling the story of the United States. He places special emphasis on America’s place in the history of advancing Western Civilization. He begins with our classical roots and ties to ancient Hebrew, Greek, Roman, and Western European institutions. Just as importantly, he accurately weaves the story of Christianity and Christian values into the American story… John relates the truth about the American past by telling about our many good qualities and accomplishments as well as the setbacks our nation has endured during its long history…Young American history students and their teachers have long yearned for a book like the one you now hold in your hands. —Michael Allen, Ph.D.

Michael Allen, Ph.D., co-author of the #1 New York Times best-selling book, A Patriot’s History of the United States. Professor at the University of Washington, Tacoma and Editor of The Story of Liberty, America's Heritage Through the Civil War

As Reviewed by Cathy Duffy

FAQ

1. Should the teacher or homeschool educator start with the Teaching the Socratic Discussion in History Seminar?

The Teaching the Socratic Discussion in History Seminar prepares classroom and homeschool educators to teach History using a Socratic approach. If you have never taught using the Socratic Method, we recommend starting with the seminar.

2. Will this curriculum work in a homeschool history class with 1 student, or in a classroom setting of 30?

This classical history curriculum has been successfully used in both situations. In a homeschool setting with one student, the parent challenges the student to develop arguments for both sides of a Socratic discussion question. In a classroom or small group setting, students debate and discuss with one another and the teacher acts as a facilitator.

3. How do the history text and the primary source documents fit in with the Take a Stand! student book? Are they integrated?

Yes. The Take a Stand! Teacher Edition contains detailed lesson plans that explain when, in each lesson, to read the history text, what to assign for homework, what to do in each lesson, and when to read the primary source documents. The entire curriculum is seamlessly integrated. This classical history curriculum has been refined over the course of a decade of use in various settings.

4. About how much time should I allot for History work each lesson/day/week? I know each student is different, but a general timeframe could be very helpful for planning purposes.

In a homeschool setting, we recommend that lessons take place once a week for one hour and a half. In the first half hour, play the Classical Historian Go Fish game that most closely aligns with the curriculum. Begin with the go fish game, and then switch to the “collect the cards” version of the game, which teaches historical facts, chronology, and inductive thinking skills. Then, plan under one hour for the lesson.

In our Online Academy discussion courses, we meet for 30 50-minute lessons each year. In a classroom setting, plan on interspersing the 30 lessons throughout the year. One teacher shared that she enjoyed teaching this curriculum once per week where she had a Socratic Discussion day. Another teacher shared she enjoyed teaching this in chunks, such as one week every six weeks or so.

For teachers who will be assigning essays, our Teaching the Socratic Discussion DVD Seminar goes into great detail about timing related to first drafts and revisions.

5. What is the difference between the high school and middle school levels?

In our high school history curriculum, the readings are longer and more complicated, and the Socratic discussion questions are more complex.

6. How much time should I plan on having my child do the homework?

If the student is not writing any essay, junior high students can usually complete the homework anywhere from 30 minutes to one hour per week, and high school students from two to five hours per week, depending on their reading skills. If essays are assigned. it really depends on the length of the essay (one-paragraph, five-paragraph, or more) and the age and skill of the student.

7. I see the middle school history curriculum comes with Socratic Discussion DVDs specific to the curriculum. How do I use those?

Teachers may use our recorded Socratic discussions in a variety of ways. Educators can watch the discussions for further teacher training, or they can be shown to students after they have had their own Socratic discussion. Students can use these recordings as an “answer key” for their own discussions. Additionally, students could watch these before they have their own discussions and take notes to help them prepare.

8. I don’t know much about history. How can I teach this?

We’ve all had history teachers who know “everything” and they were poor teachers. For teachers of the junior high curriculum, you can read the history along with your child and it would take about 10–20 minutes a week of reading. For high school, it would require from one to two hours per week of reading.

9. Do I need to complete every single thing that is recommended in the Teacher Edition?

No. In the end, the teacher has complete authority to make judgement calls based on the situation and what the think is best. We recommend that all students read the entire history text and engage in as many Socratic discussions as possible. We planned the curriculum to include essays for each chapter because persuasive writing is an important component of good scholarship. However, teachers may use their judgement as to how much work they want to plan for their students.

10. How does this curriculum work and how is it unique?

Classical Historian teaches students to think independently, read, write, and speak effectively, AND learn history. We use a four-step method:

1. Students learn the Tools of the Historian.

2. Students are challenged with Socratic discussion questions.

3. Students research a variety of primary and secondary sources.

4. Students engage in a Socratic discussion.

For more specifics, visit our Methods Page.

The Teaching the Socratic Discussion in History Seminar prepares classroom and homeschool educators to teach History using a Socratic approach. If you have never taught using the Socratic Method, we recommend starting with the seminar.

2. Will this curriculum work in a homeschool history class with 1 student, or in a classroom setting of 30?

This classical history curriculum has been successfully used in both situations. In a homeschool setting with one student, the parent challenges the student to develop arguments for both sides of a Socratic discussion question. In a classroom or small group setting, students debate and discuss with one another and the teacher acts as a facilitator.

3. How do the history text and the primary source documents fit in with the Take a Stand! student book? Are they integrated?

Yes. The Take a Stand! Teacher Edition contains detailed lesson plans that explain when, in each lesson, to read the history text, what to assign for homework, what to do in each lesson, and when to read the primary source documents. The entire curriculum is seamlessly integrated. This classical history curriculum has been refined over the course of a decade of use in various settings.

4. About how much time should I allot for History work each lesson/day/week? I know each student is different, but a general timeframe could be very helpful for planning purposes.

In a homeschool setting, we recommend that lessons take place once a week for one hour and a half. In the first half hour, play the Classical Historian Go Fish game that most closely aligns with the curriculum. Begin with the go fish game, and then switch to the “collect the cards” version of the game, which teaches historical facts, chronology, and inductive thinking skills. Then, plan under one hour for the lesson.

In our Online Academy discussion courses, we meet for 30 50-minute lessons each year. In a classroom setting, plan on interspersing the 30 lessons throughout the year. One teacher shared that she enjoyed teaching this curriculum once per week where she had a Socratic Discussion day. Another teacher shared she enjoyed teaching this in chunks, such as one week every six weeks or so.

For teachers who will be assigning essays, our Teaching the Socratic Discussion DVD Seminar goes into great detail about timing related to first drafts and revisions.

5. What is the difference between the high school and middle school levels?

In our high school history curriculum, the readings are longer and more complicated, and the Socratic discussion questions are more complex.

6. How much time should I plan on having my child do the homework?

If the student is not writing any essay, junior high students can usually complete the homework anywhere from 30 minutes to one hour per week, and high school students from two to five hours per week, depending on their reading skills. If essays are assigned. it really depends on the length of the essay (one-paragraph, five-paragraph, or more) and the age and skill of the student.

7. I see the middle school history curriculum comes with Socratic Discussion DVDs specific to the curriculum. How do I use those?

Teachers may use our recorded Socratic discussions in a variety of ways. Educators can watch the discussions for further teacher training, or they can be shown to students after they have had their own Socratic discussion. Students can use these recordings as an “answer key” for their own discussions. Additionally, students could watch these before they have their own discussions and take notes to help them prepare.

8. I don’t know much about history. How can I teach this?

We’ve all had history teachers who know “everything” and they were poor teachers. For teachers of the junior high curriculum, you can read the history along with your child and it would take about 10–20 minutes a week of reading. For high school, it would require from one to two hours per week of reading.

9. Do I need to complete every single thing that is recommended in the Teacher Edition?

No. In the end, the teacher has complete authority to make judgement calls based on the situation and what the think is best. We recommend that all students read the entire history text and engage in as many Socratic discussions as possible. We planned the curriculum to include essays for each chapter because persuasive writing is an important component of good scholarship. However, teachers may use their judgement as to how much work they want to plan for their students.

10. How does this curriculum work and how is it unique?

Classical Historian teaches students to think independently, read, write, and speak effectively, AND learn history. We use a four-step method:

1. Students learn the Tools of the Historian.

2. Students are challenged with Socratic discussion questions.

3. Students research a variety of primary and secondary sources.

4. Students engage in a Socratic discussion.

For more specifics, visit our Methods Page.

Have you watched the video and read everything but still have a question?

Email John De Gree and he will email you answers or set up a phone conversation with him.

Email John De Gree and he will email you answers or set up a phone conversation with him.

For information about The Story of Liberty Video Course, click HERE.

Scope and Sequence

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.