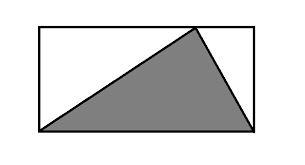

This year, I decided to take a new course offered at my college, called Teaching Elementary Math. I expected that it would address each word in the title uniquely, but I hadn't expected to learn about teaching math in an imaginative, inspiring way. This past week, through our assigned readings and class lecture, I realized that math is much more based on unreal things than reality. For this reason, math needs to be taught in a different way that most people teach it now. When people think about math, they usually think about formulas, problems, and boring class lectures. They associate math with something tangible, objectively correct, and sterile. That is probably because the math which non-majors usually are exposed to is pointed towards two main purposes: 1. To teach children how to do basic arithmetic, and 2. To tangibly test schools and the ability of teachers through standardized tests. Although these two things are appealing, there is a beauty in math as a creative, abstract art, which often times gets forgotten. In math, we are forced to think of things differently. A large part of math deals with the imaginary world. In calculus II, students are asked to find the area of infinite curves rotated around axis. This sounds crazy! But there are actual, correct answers to this question. But even more on the basic level, we have to use our imagination to find more basic answers to elementary questions. Think about a triangle for a minute. How do we find it's area? Instead of thinking of the formula, or exiting out of this blog to google it, think about how we would get the area from areas of shapes similar to the triangle. Surround the triangle with a rectangle, so that the triangle is completely encaptured. The height of the rectangle is the same as the height of the triangle, and the widths and lengths also equate. Now, draw a line down the height of the triangle, and what do you have? Two boxes split down completely in the middle, making sense of our formula, 1/2bh. We had to think about math in a different way than normal, coming up with a more imaginative way to solve the problem than just regurgitating the formula and plugging away numbers. In the classroom, we discussed how to apply this different way of teaching math so that the students are engaged and challenged. My professor showed us that the best way to challenge the students is to teach math through the Socratic method, asking guiding questions so that the student ends up learning the desired material more organically instead of having it thrown to them. In this way, learning becomes slightly hidden, and the student will hopefully understand why specific theorems in math make sense. My professor suggested that each class begin with a question that should be challenging but doable, with its discovery as directly related with the larger topic of class. Through engaging with the students, the professor guides the students through their thoughts and helps them learn how to use their imagination to understand the class topic. Although it is important to be able to know formulas for quick arithmetic, being able to understand them and why they are important is so special, it is sad that math has been quantified and subjected to standardized testing. With so much pressure to teach students about formulas and drills, teachers may easily forget that math is beautiful too. It is like music. When we just see notes on the sheets, we can add them up to count how many beats fall in a measure. But when we play the music, the notes pluck at our heartstrings and we are forever changed.

4 Comments

John Milton was a famous 17th century poet. He is most famous for his epic, Paradise Lost, but he also wrote many brilliant shorter poems in preparation. From his Familiar Letters, we know that he felt called to write this epic, but that he hadn’t yet felt prepared enough to write about the Fall of Man. Through writing shorter poetry, he determined that he would be ready for his great work, and arguably one of the greatest works in British history. One of Milton’s common themes to his writing is the importance of the transcendence. This idea, which has been explained by many thinkers and Church Fathers, has shaped the Liberal Arts. Through believing in something which transcends pastoral reality, people have a basis for forming their arguments. In seeing that the things of the earth fades, it is easy to see the validity in Milton’s claim that there must be something which transcends that which fades. Milton argues that people should focus on the things which transcend, such as God and soul, rather than things which ultimately will not have importance, such as earthly goods and fame. Milton was not the first to argue this viewpoint. Many of the philosophers of antiquity argued this idea. In the Phaedo, Plato responds to questions for his lack of fearing death by simply stating that it is in the office of the philosopher to consider the afterlife, and ponder death, thereby preparing himself for death. By the time death comes, he should be well prepared in thought by philosophizing his whole life. While Plato believed in a different vision of the soul than Christians like Milton, he was right to focus on things eternal than mortal. Further along in Western Tradition, Church leaders discussed the right treatment of earthly goods. St. Augustine of Hippo famously wrote about ordinate desires, and the hierarchy of goods. In St. Augustine’s Confessions, Augustine argues that everything is good in its order. For example, Love is good and from God, but when human love is placed about the love of God, through various means, it is tinted and becomes sinful. This applies to other goods, such as food or earthly possessions. God gave humans food and earthly things so that we can survive, but when these objects are placed above God, they too become distractions from the Good and therefore are not good anymore. Milton builds on the argument of the powerful eternal glory over earthly goods through his rich poetry. Many of Milton’s poems allude to the great thinkers of the past, and enhance their arguments with iambic pentameter, or blank verse. He argues that mirth is a means for us to live, but he chooses melancholy. He uses light and darkness to highlight the Truth in God and the lies in the devil or inordinate desire. And he describes Jesus as a powerful yet merciful savior. A few of my favorite poems are On the Morning of Christ’s Nativity, L’Allegro and Il Penseroso, and On Shakespeare. In recent years, the term “adulting” has skyrocketed in its use to mean the responsibilities associated with being an adult. “To adult” means to take on the responsibilities of a normal adult, such as doing the laundry, paying bills, working a steady job, etc. Many people have started using this word as a verb in their dictionary to express their transformation from living within their parent’s care to living on their own. It is not altogether uncommon to hear someone who just payed off their first bill say, “Man, I just adulted today.” Or, if someone admits to tiredness after being responsible for themselves from doing grown-up things, such as buying and cooking their meals, cleaning up after themselves, working, and exercising, they might say, “I adulted too hard, it’s time for Netflix and ice cream.” These examples display how the use of this word can have a negative effect on the attitudes towards becoming an adult. It is good to recognize this growth from parental reliance to independence as an accomplishment. However, bragging about this change, which should be viewed as a difficult but necessary one, glorifies the difficulties associated with being an adult to an unhealthy extent.

Becoming an adult and accepting the responsibilities with it can be a challenging thing, but it is also a challenge which everybody has to go through, and one which ultimately should be anticipated. Once someone reaches the legal age of adulthood, they should be ready for independence. Around the age of fifteen, many teenagers will start working odd jobs, such as babysitting or walking dogs. Some may even work more official jobs, such as working at restaurants or clothing stores. At the age of sixteen in most states, teenagers can test for their driver’s license, and learn how to transport themselves to their own activities. But even perhaps more importantly than driving or having a job, teenagers start understanding the world at deeper levels. They have more advanced thought processes, and have already formed judgments about their upbringing–agreeing and disagreeing with certain things. Thus, after experiencing life for eighteen whole years, people should be ready to take care of themselves. They have most likely received an education, had the opportunity to work, and been able to think about things at a more advanced level. Through using the diction of today’s culture, young adults glorify the challenges they face, and more easily succumb to complaining or abandoning their responsibilities. Throwing about the “verb” of “adulting” in daily speech shows that doing that which is expected of someone should be praised instead of assumed. It gives something which should be accepted and anticipated–independence–a negative connotation, and thereby drains youth from their anticipation of independence. On the Friday of this past week, I declared my Spanish and English double major at Hillsdale College. Hillsdale's English department is known to have some of the hardest professors. Yet, like the motto which Hillsdale's students proudly affirm during tough times in the school year, "Strength Rejoices in the Challenge," I am ready for this test, and most certainly ready to accept the positive changes which will result from my instruction from these famous professors.

The following essay is a Short Analysis essay of an excerpt from Huckleberry Finn from my past semester's English 300 level course, American Literature 1820-1890: Huckleberry Finn Excerpt “My plan is this,” I says. “We can easy find out if it’s Jim in there. Then get up my canoe tomorrow night, and fetch my raft over from the island. Then the first dark night that comes, steal the key out of the old man’s britches, after he goes to bed, and shove off down the river on the raft, with Jim, hiding daytimes and running nights, the way me and Jim used to do before.[1] Wouldn’t that plan work?” “Work? Why cert’nly, it would work, like rats a fighting. But it’s too blame’ simple[2]; there ain’t nothing to it. What’s the good of a plan that ain’t no more trouble than that?[3] It’s as mild as goose-milk. Why, Huck, it wouldn’t make no more talk than breaking into a soap factory.” I never said nothing, because I warn’t expecting nothing different; but I knowed mighty well that whenever he got his plan ready it wouldn’t have none of them objections to it.[4] And it didn’t. He told me what it was, and I see in a minute it was worth fifteen of mine, for style, and would make Jim just as free a man as mine would, and maybe get us all killed besides.[5] So I was satisfied, and said we would waltz in on it.[6] I needn’t tell what it was, here, because I knowed it wouldn’t stay the way it was. I knowed he would be changing it around, every which way, as we went along, and heaving in new bullinesses whenever he got a chance. And that is what he done.” Essay In this selection from Huckleberry Finn, Mark Twain uses the interaction between Huck and Tom to illustrate a common hardship in youth. Leading up to this point in the novel, Huck had established a system of moral standards. Huck had decided he would rather “Go to Hell” than live according to society’s standards with the treatment of black people (Twain, 341). However, through the boys’ discussion, Huck shows that he fails to live up to this ideal. Through Twain’s use of Tom as a symbol of society, Huck’s quick submission to Tom demonstrates both Huck’s denial of his ideals and his regression in character. Twain uses Tom as a symbol of society through Tom’s exemplification of the common boy and the common attitude towards black people in order to juxtapose Huck’s newly established morals with the morals of society. Although Tom is a rather rambunctious boy, people in society view him as one who is civilized. Tom attends church, goes to school, and is a leader among the children in town. Most central to this passage, however, is the reflection of society through Tom in his perspective of Jim. Even though Tom knows that Jim is legally free, he still tries to rescue Jim with Huck so as to get a rush from the adventure and fame. Tom is in favor of a plan with “style” because, although it might “get them all killed,” rescuing Jim in an extravagant way would benefit him. Therefore, much like the way society values black people solely for their utility, Tom values Jim only insofar as he can aid Tom. In contrast, Twain juxtaposes Huck’s rescue plan with Tom’s to show that Huck initially had a different attitude towards Jim than society. After Huck tells Tom of his rescue plan, Tom says, “Work? Why cert’nly, it would work” (359). Here, Twain uses a question to illustrate Tom’s bewilderment with Huck’s purpose in his plan to show how radically different both purposes are. While Huck is initially concerned with rescuing Jim in the most humane way, Tom shows that merely rescuing Jim’s life for Jim’s own sake is pointless. Through initially juxtaposing both purposes for Jim’s rescue, Twain prepares his platform for illustrating Huck’s transition of his moral ideals. Twain juxtaposes Huck’s quick consent to Tom in this excerpt with Huck’s earlier thoughtful and long processes of logic to demonstrate Huck’s failure to live up to his newly formed ideals. In chapter three, Huck doubts both the usefulness of prayer and Tom’s assertion that a Sunday school picnic is, in fact, a group of Arabians and Spaniards. When Miss Watson explains prayer to Huck, instead of just believing Miss Watson right away, Huck wanders off into the woods and thinks about the benefit of prayer. Similarly, instead of going along with Tom’s claim about the Arabians and Spaniards, Huck thinks about the logicality of tom’s story and concludes that it is a lie after the length of a couple of days. In both cases, Huck spends time in thought about these issues. In contrast, in this passage, Huck quickly gives his consent to Tom’s plan, saying, “I seen in a minute it was worth fifteen of mine.” Twain clearly demonstrates Huck’s failure to uphold his ideals because Huck only thinks about Tom’s plan for a minute, then fully consents. Because Tom is a symbol of society, Huck’s quick consent to Tom’s plan shows Huck’s transition from believing in his ideals independent from society to consenting to societal morals. Furthermore, Twain shows Huck’s quick change in ideals through a short sentence. When Huck describes how readily he thinks he will accept Tom’s plan, he says, “And it did.” This short sentence illustrates the short amount of time Huck places in evaluating Tom’s plan. Additionally, Twain demonstrates Huck’s enthusiasm with Tom’s new plan through the use of casual diction. When Huck states his agreement with Tom, he says, “We would waltz in on it.” By saying “waltz,” Twain suggests that Huck does not regard rescuing Jim as something serious. This word makes the reader think that Huck will carry out Tom’s plans with more of a causal attitude than a solemn one. Twain demonstrates Huck’s regression in thought by Huck’s quick consent to Tom. In conclusion, Twain uses Tom as a symbol of society to show Huck’s failure in keeping his ideals against those of society. Through juxtaposing Huck’s newly formed ideals with Tom’s reflected morals of society, Twain initially establishes Huck’s ideals in contrast to the ideals of society. But, through depicting Huck’s quick consent to Tom in this passage, Twain shows Huck’s hardship in keeping with his new resolution. Works Cited: Twain, Mark, and Tom Quirk. The Portable Mark Twain. New York: Penguin, 2004. Print. |

Jessica De GreeJessica teaches 5th grade English and History as well as 11th grade Spanish III at a Great Hearts Academy in Glendale, AZ. In addition to teaching, she coaches JV girls basketball and is a writing tutor for The Classical Historian Online Academy. Jessica recently played basketball professionally in Tarragona, Spain, where she taught English ESL and tutored Classical Historian writing students. In 2018, she received her Bachelor's degree in English and Spanish from Hillsdale College, MI. Archives

April 2020

Categories

All

|

|

SUPPORT

|

RESOURCES

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed