|

This past week, I had the honor of speaking to Mr. Martin Masat. Born just six months before the Prague Spring invasion, Mr. Masat grew up during the 'normalization' period in Czechoslovakia. Communist indoctrination was a normal thing for him, and he didn't really notice a lack of freedom until he was a young adult. When he was a student at the University of Economics in Prague, he experienced the fall of communism first hand. He more than experienced it, he aided in its destruction. Presenting about the student's strike to outside villages, Mr. Masat tried to spread the truth to the people around him. And that's what we want to do today--spread the truth about communism. In the words of Mr. Masat, "the basic idea of communism is to help the poor people. It's difficult to understand that maybe the basic idea might be nice but it will never ever work in practice, and what will always happens is that some totalitarian state will evolve from it." Peak into the life of someone shaped by communism. The very life which was molded by communist teachers and pionyr scout leaders, then beaten by the law behind closed doors, without a trial.

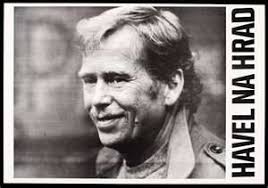

The following conversation has been edited for clarity. Part I: Childhood to Young Adulthood D: Welcome back to Life during Communism: a Conversation Series. Today I have with me Mr. Martin Masat. He was born in January 1968, putting him at 6 months old during the Prague Spring invasion. He studied at the University of Economics in Prague. He currently works as a transaction advisor for the KP and G international company. He currently lives in Czech Republic with his family. Thank you for being with us today. To start off, I’d like to ask you about your childhood, youth, and your experience with school. What were some of the communist influences in school? Did you enjoy school? M: Hi Jessica, hi everybody. I would say when you were a child at that time, when I was, meaning the 70s, you wouldn’t really think that something is not normal, or that something strange is going on. You would just live your childhood, have your normal problems. School, I don’t know. Now I think that I enjoyed school, but then I probably wouldn’t say that I like school. When you speak to children, not many say they like it--it’s kind of a duty. There’s nothing for me that would be not normal. One of the influences, obviously, there was a youth organization for the children which was called Pionyr. It was kind of obligatory, a very small percentage of children didn’t attend. Normally, about 90-95% of children in schools were members in this organization. It really depended on the teachers and people involved. At summer schools I heard stories that people had to spend an hour a week, with boring stuff, sitting in the class and hearing about the greatness of the Soviet Union. Another classroom would have a couple of meetings, a couple of trips. It wasn’t as seriously taken. That’s something you would notice-another duty on top of school-but again nothing markable. My parents didn’t really want to mess me with politics or anything, so they didn’t talk with me or in front of me about politics. Obviously they didn’t want me to say something wrong in school, or want me to lie in school. Some of the teachers were communists and were promoting it. But most of the teachers were silent. They did their jobs and taught the students. It wasn’t something you would notice as “oh, I’m locked, I’m not free.” Most children didn’t notice it. The second thing you noticed were Czech flags. It was 30 years after WWII. All the people still had memories about it. When we started drawing pictures, we always drew soviet or Russian tanks freeing us from the Nazis. It was always something which influenced the children, the young people. On TV there were movies about brave Russian soldiers. There was a famous polish series about four brave russian soldiers and a dog. So it was kind of made for children. Kind of difficult to compare. You guys have superman, we have russian soldiers fighting Nazis. In the second part, the years when I attended 5,6, and 7th grade you started noticing some things. You spoke to people who knew about Prague Spring, or found some old magazines. So obviously you started thinking about these things. However, it was not black and white. The idea of communism is very different from fascism. The basic idea is to help the poor people. It’s very hard to change your opinion because the basic idea is something that everyone can believe in. D: You talked a little bit about the Prague Spring invasion. Did you learn about it in school or did anyone mention it? M: No. The Russian army freed us in 1945, and from then on we had been friends. D: In class, did you ever talk to any of your classmates about communism, or did you know not to ring up? M: Well, you could meet occasionally some people with a strong mind, one way or the other. But most people didn’t speak about it. At the elementary school, we didn’t even learn the 20th century. Even Masaryk and the first republic. Obviously we were taught about the second war but it wasn’t really a part of the history or studies, it was a part of everything. Regarding communists, I can tell you our class teacher was a very strong communist teacher and she was really believing in communism. Trying to persuade us that everything is good. And, to be fair, she was a good teacher in terms of her being professional and her effort to teach us something. When I spoke to the guys, you know how in every class you have bad boys who always have troubles. I was not one of them. But when I spoke retrospectively to one of them they said she was very tough but she fair. If there was one of those good guys, who are very proactive, and made some problems, she was hard on them as well. So you could say she was tough, she was communist, but she was a good teacher. Maybe even a good person. Difficult to see from the point of a child. When you speak to people later, you realize that in the 70s, there weren’t many communist believers. The people simply realized that something was wrong. People in the 50s and 60s believed in it, but after 1968, 90% of those people realized that there was something wrong. At the same time it’s an example that the Communist Party ruled the country. They had a system of head hunting relatively good people. If you were good in your profession, you had a chance that people would come up to you, say that you’re good, you’d classify to be a communist, and offer you a position in their business. You can join us and become a high director, or you don’t have to. And that happened to me at the university. In my first semester, I was nervous and made a big effort, and was one of the top two in my class. And one of the teachers (and 90% of the teachers in the University were communists, not at the elementary school, but the teachers at the university had to be) came to us and offered us a position in the Communist Party. And we both told him no. And there were no consequences. I can imagine if it were some other person it would maybe be an issue. But many of them were reasonable and didn’t do anything. D: I’m glad you started talking about the University because I have a few questions about those. Did you have to take any special exams and tests to enter the University, and did any of those have any special communist influences? M: At the University we had normal exams. We studied at the University of Economics so some of our questions were based on Marxist and Engels theories. Some of our exams were part of the economics incorporated in the socialist/communist theories. If you were asking to join the University, you had normal exams with Mathematics, maybe Russian--Russian was common, you had to learn Russian--and such, but nothing special really. Obviously you had to present your CV and you had to have some commentary from your school. So, if you were a child of some dissidents, so obviously the university would be told. And you wouldn’t get in, the University would make it so that you didn’t pass the exams. Regarding university, the socialist economics was funny. There was something called Political Economy of Capitalism which was the Marx/Engels and Political Economy of Socialism which was complete nonsense but you had to pass it. And there was something really strange, like the History of Communism, which you somehow passed. It was nonsense. There was no logic in it, no benefit in it, and the people who taught were ok. They were the old people who fought in the Slovak Revolution against Nazis, and they didn’t know how to teach, but they had good qualification from fighting. It was partly fun, partly nonsense, you had to suffer through it. If you did it, you did it. It wasn’t the biggest pain. What was more painful were the soldiers classes, which we had to attend in the second and third years. We had to spend one day a week practicing to be a soldier, and you had to pass an exam. If you didn’t pass the exam for these classes you couldn’t graduate the University. So it was a pain, it was a difficult time. Also, survival. D: Survival classes? M: I mean, yeah in those times it wasn’t very good times from the democracy or freedom perspective, but you could live. You weren’t afraid that you would be killed from your dissidents. D: Thank you so much for taking your time. M: Of course Part II: Young Adulthood D: Welcome back to the Life during Communism: A Conversation, I have with me Mr. Masat. Earlier we discussed his experience with communism when he was a child in elementary school. Fast forwarding to his early teen years and young adulthood, he looks at the situation much differently. M: Hello D: In the 80s, what did you think about communism? M: If you speak about official propaganda, it was very clear. It was part of daily life. Everyday you heard on the news that life is so great in our country, thanks to the Communist Party, thanks to our soviet union friends, where the Western Imperialists, like USA, France, UK, and other countries, are only trying to make war. So it was a very black and white diction of how the world is. Obviously in our country everyone had to have a job, it was a law that you had to work. On the other hand we were told that there was so much unemployment. There were very big differences between the rich and poor people in the Western world. So, that was the official propaganda in our country D: What were the sources of propaganda? M: TV and newspapers. Obviously it was not possible to get foreign or Western newspapers. It was illegal even to bring any into the country. Although you could listen to a couple of radio stations. Radio Free Europe and Voice of America. They broadcasted in the Czech language. The Communists were trying to, not really shut them down, but damage the signal. But it was kind of like, I even don’t know if it was illegal to listen to them. Obviously if you were caught, you would find difficulties in your job, in your work, but you wouldn’t be arrested. You weren’t supposed to listen to it, but it was possible. That was the source of information from the other side. The travelling was limited. We were basically free to travel to the Eastern part of Germany, so it was really difficult to get direct experience. On the one hand, you understood that the official propaganda was lying to you, but on the other hand, you didn’t really know the truth. So it was difficult to make your mind. There were a couple of phenomenons that you really noticed. Emigration. There were some famous sportsmen, tennis players, hockey players, singers. If life is so good here and not there, why are people leaving here, and not the other way around? That was one aspect of it. So, some information was limited and you had to make your mind with limited knowledge. The vast majority of the people understood that the freedom here is limited. D: How impactful would you say was Radio Free Europe and Voice of America. How impactful were their broadcasts in changing the opinion of the people from official propaganda to the truth? M: It was really important. Otherwise, you would have really only limited rumors. So it was important. Many people were listening to it. This was a source of information where I learned that there is some dissent. There is Mr. Havel. There are people being arrested not just for their thinking, for their mind. I would say it was important. Itself wasn’t necessary to change things, but it was important in keeping people's’ eyes open. D: Leading up to the Velvet Revolution, did you sense the fall of communism from the atmosphere of the people? M: The atmosphere in the late 80s was definitely changing. It was not changing too much. Just in little strides. In our country in the 80s, folk music and country music became popular. It’s slightly different than folk music in your sense. It’s not really the old music of the nation, it’s more like Bob Dylan, and these kinds of singers. There was a boom of this kind of music. Here there were big festivals. They were official festivals. In the first plan, or first idea, it was nothing controversial. But you could see that some of them started to be a little bit more brave. To start putting hidden messages in their songs. There were continuous pressure. You could see that it was evolving and it was more and more possible to be open about things. If it was too much, then some censura came in and the singer was prohibited to sing. On the other hand, you could see that some of the previously prohibited singers were suddenly allowed to sing. One of them, was prohibited many many years and then suddenly, in 1988, I went to one of his live shows, official, or semi-official. To be very frank, all of this was because of Mr. Gorbachev and his Perestroika. What was happening in the Soviet Union at that time and other countries was not really happening here. But, I went to Poland and Lietuva in 1989, and I was shocked by the life there. There was freedom. There were official newspapers describing things really shocking to us. I realized, there are big things happening around us, we must also receive change. Another thing which helped was the visit from the French president, Mr. Mitterrand. One of the promises the Communists made was that they allowed him one official dissident formation. For the first time in my life I saw with my own eyes Mr. Havel, yeah. From those, you could really predict that something was really happening. D: It must have been a really awesome thing to be a part of. An awesome feeling. M: Yeah, and then there were some unofficial protests which started in 1988 for the anniversary of Mr. Palach. So there were so called “Palach week.” So especially in 1988 and 1989 there were very big protests. I personally did not attend them, but they were really close to my house, so from my window I could see some of the people running and policemen chasing them. Then there were protests in the Northern part of the country where there were bad situations with the pollution. And there were protests with the factories. You could call them environmental protests. But obviously the Communists forces took them as protests against the Communist Party. They were protests where people were arrested. There were protests where there were policemen with water guns. So you could predict that at one point something will happen. D: During the Velvet Revolution, did you ever attend any of the protests? M: Yes, I attended the manifestation on the 15th of November. A couple of friends told me about it. It wasn’t officially promoted. But it was officially out. It was the anniversary of the Nazis killing a couple of students and closing the University during the occupation. But the thing was that it was co-organized by a couple of independent student organizations. There were some people who spoke who were very open with their criticism of the current situation, of zero freedom. So it turned out to be a very anti-communist protest. So it became something that students didn’t want to end, and we decided to march. And the police forces were following the march and stopped it at some point. And I was arrested and locked in the police house until midnight. D: Were you beaten by the policemen? M: Yes, not in the streets, but in the police station, yes. You know, I don’t like a big number of people together, so I was in the end. So they took me. D: You were an easy target. M: So to speak. So that was my experience. It was Friday. I didn’t know what was happening in the streets, but later I knew that there were lots of beaten students. Because it was in the city centre, close to some theatres, it was spread to the artists, actors. So the next day, the artists started a strike. The strike was like this: the shows were not canceled, but people came to see some theatre, and the actors would go on the stage and say we are not going to act, but we will talk about what’s happening in the streets. And then the students went on strike on Monday. It was very difficult to communicate. But some students ran from one University to another and spread the news. And, one thing was, there was spread fake news. And it’s still unclear how it was spread, but the fake news was that one of the students was killed. I personally think that for some people it was the catalyst or the point when they said they needed to do something. And that was the point where on the other side the Communists started to be afraid, to say they did too much. So the strike was where we went to the Director and said we will not go to school but we’re occupying it. At most schools this really happened. And you spent a couple of days and nights in the schools, locked sometimes. You could go out but you didn’t want to because you didn’t know what would happen. After the artists got more brave, some of the newspapers printed what happened on the 17th of November. They started to publish the requests of the students. One of them was to change the base law which stated at the time that the ruling party needs to be a Communist Party. To obviously that was difficult to swallow. So at that time you didn’t really know if the army would come and force us from the school. Or if they’d only accept five of the ten terms. There were a couple of days where we felt really nervous. We spent the time by taking trips to the country. We didn’t have internet. What happened was that there were lots of posters, we want to change the system, we want freedom, students are on strike. In the small towns outside of Prague it was more difficult to persuade the people that things were changing. So we did some trips, some road trips, to present there. D: That’s awesome, that’s really inspiring. It sounds like it was primarily a student-run protest. M: Like what I said it was just chance that it happened like that. The catalyst could have been the environmental protests. At that time, yeah. You can see it once in your night, yeah. I was walking around Prague at night, told the taxi driver that I was a student, and got a free ride. D: Wow, that’s a lot of respect. Do you remember celebrating the end of communism? Do you remember the point at which communism fell? M: We speak about the Velvet Revolution, which was the 17th of November, which you know at that time the Berlin Wall had already fallen. So we were one of the last countries before Romania. So I would say that the really deciding date it was the last day, the 29th of December, where Mr. Vaclav Havel was voted president. It was very clear. Now the world would really change. D: How soon did you see change? We talked about the Velvet Revolution being the 17th of November and Vaclav Havel becoming president in December. That’s a short amount of time, politically speaking. How soon did you see change in everyday life? Did you still have to wait in cues for food? M: Definitely no. The economical situation didn’t change from day to change. Definitely there was change in your mind and change with what you could say in public. But, for example, if you wanted to travel during communism, you had to submit an official application for travelling abroad, and an application for exchanging money. And you had to simply wait. The answer from the officer could be, sorry, we don’t have enough Hungarian money, you cannot go there. And that changed relatively immediately. Simply, they said we don’t have much foreign currency. So they split the package and gave out the calculated quota per person. So everyone didn’t really have a lot of money but everyone was in the same situation. So I immediately went to Greece in 1990 with just a couple of Euros in my pocket. But I was free to travel. D: Oh, interesting. Do you see any lasting effects of communism on people? Are some people still affected by communism, and wear an affected attitude? M: It’s difficult to say. I would say that in the 70s and 80s noone was really believing in the idea of communism anymore. In the 90s you suddenly could do your business on your own, be an entrepreneur, that was illegal before. So people who used to be less risky started to be more brave with their money. But, it’s a difficult question. There are many aspects, and it’s hard to say what was the cause of change. During communism, you had one or two or three choices. Now you have big supermarkets, with lots of choices. So people started to change, started to be numerous. There are many possible changes. D: Looking at the world right now, do you think a conversation about communism and Czechoslovakia have a role in society, and how big of a role does it have? M: Yeah, people tend to remember the good things and forget the bad, especially from their childhood. I think it’s definitely important to have this in mind. It’s obviously difficult to capture all of the aspects. It’s difficult to be fair and explain everything to people who didn’t live during communism. Now, where there’s lots of social media, what I call the Twitter period, where people are used to expressing themselves in one sentence, it’s very easy for propaganda. If you want to confuse people, it’s really easy to just post on Facebook “it was much better at this time.” without explanation. There’s room for lots of garbage on the social networks. D: I agree with you, people have become dull to doing their own research. If it’s so easy to just click on the phone, they won’t do more research. M: IN my country, I’m surprised by how many positive messages you can find about Russia and China, and you don’t know who’s writing them. There are still some kind of Cold War or, we have to fight for the democracy still. It’s not automatic. D: Right, freedom’s not free, you have to fight for it. I love it! To close the interview, do you have anything you’d to add? M: I might think about something later, I’m a little bit exhausted. Sorry for my English. I’m not a native English so sometimes I don’t express myself very well. It’s still a big topic, unfortunately. You can imagine that the basic idea of communism is to help the poor people. It’s a very basic idea, so it’s very difficult to understand what is wrong with it. And that’s something which we discussed at the University, but for some of the less educated people it was difficult to understand. It’s difficult to understand that maybe the basic idea might be nice but it will never ever work in practice, and what will always happen is that some totalitarian will evolve from it. Although you can point to some of the short, limited periods or areas where the communist idea, where everyone shares everything together, might come to practice, like some of the Jewish cities, or the city of Tamor in the Hussite land in old Bohemia in the beginning of the 15th century. Apart from the Jewish villages, the experience is always that the outcome of trying to introduce this into practice will be a disaster. D: Well thank you so much for talking with me. It’s been really interesting to hear about your experiences, and thank you so much for sharing with me and others about communism. M: Thank you for being interested.

0 Comments

Dr. Zbynek Skvor grew up in Czechoslovakia during communism. He was born in the early 1960s, and has experienced many of the different phases of communism in the country, including a brief period of liberalization during the Prague Spring, the communist's strict reinforcement of censorship during the 'normalization' period succeeding the Prague Spring invasion in 1968, the Velvet Revolution, and the democratization of the country once freed from communism's grip. His story is an inspiring one. When he was a little child, he went to celebrate Dubcek's more liberal government in his father's arms. One of the first words he wrote was "Democracy." Later, not allowed to continue his studies in secondary school, he was forced to work in the underground metro system. Nonetheless, he pursued his love of Electromagnetism and found a way to study. Now, he is the Department Chair of Electromagnetic Fields at the Czech Technological University in Prague, along as the Vice-Rector for Scientific Research and Creative Activities and the head of the Vice-Rector's office for Scientific Research Activities. Today, close to 30 years after the fall of communism, he deals with ex-communists on a daily basis.

D: I have with me the head of Vice-Rector’s Office for Scientific Research activities at the Czech Technological University in Prague, the Vice-Rector for science and creative activities and PhD studies, the department chair of Electromagnetic Field studies, and my uncle, Zbynek Skor. He was born in the early 1960s in Czechoslovakia, putting him at around 8 years old during the Prague Spring Invasion and grew up during the normalization period in Czechoslovakia post-Prague Spring invasion. Thank you for joining me today. To start off, what was everyday life like under communism? S: Well that’s difficult to tell in a few sentences. First, everyday life means that you have to get food, get some place to live, if you would like to raise your children, you would like to get them educated, and some entertainment. And all of that was somehow possible, but all of that was somehow difficult. For example, Czech Republic was quite lucky in the fact that it had enough food in the shops. That does not mean that you could buy meat everyday. There was some meat, but not good meat. There was one day a week and then you had to queue. But they were short queues like 20 minutes. And you could get the meat. And you could get other things. There have been some countries which the situation was quite different. But, Czech Republic was lucky. We had enough potatoes. There were no bananas or oranges, but you could live without bananas and oranges. Of course, sometimes if something was missing in the markets, like toilet paper, for example. Then you had to queue because you could only buy two rolls per person. Of course, this would consume so much of your time. Then sometimes you had to queue if you wanted a bed. You had to queue several times. But it was probable that sometime the bed would arrive. And after queuing several hours in the queue several times, and sometimes queuing overnight, you were in the position to get a bed. Of course this system had consequences, like slowing down your work. But you still could get along with. Of course there were people who were privileged who didn’t have to queue because they were somehow well established in the system. There were some people who had better access to medical care than others, although officially everything was, every person in the republic was equal to another person. But for example, you wanted to raise your children and get them educated. The worst things that were before, at the beginning of socialism, at the beginning there were some people who could not study at any case. For example there were some people who have sinned by having their parents own a shop. Although it still was somehow terrible. There have been real entrance exams which had 100 points for maximum. In my case when I wanted to enter secondary school, like high school in the US. If a parent was a communist, you had 10 points more, if both parents were communists you had 20 points more. But you could still get there. Unless there were some exception. Sometimes it could happen where some of your relatives said something that was incoherent with the regime. You would never find out what they did, but you were never admitted. For example, I wanted to study at gymnasium, the classic secondary school, but somehow it did not work. So finally I got skilled and I repaired the underground cars in Prague. The metro. That was my primary education. I somehow managed to get to the University. But others did not. It was quite funny. For example, when I was getting skilled for repairing the metro cars, for the whole time we were sitting in the classroom. My colleague on my left hand side was Ladislav Medved. And his family was, by the way he got a secondary degree in mechanical engineering, but anyway he was from Plzen. In Plzen he could not even get an apprenticeship. And that was because his father in 1968 was responsible for the newspaper in Plzen. He printed there, it’s difficult to say in English. The word for a big gun and an artistic picture is the same. So he had printed in the newspaper a picture with the caption of this is a collection of soviet arts, and the guns were the picture. So after this neither he, his family, although he loved the work in the newspaper, his son or daughter could not get educated in Plzen. Fortunately in Prague there was two places where a professor, although communist, took the risk to educate those people. By the way today he works with the newspaper in Plzen again. Although formerly everybody was equal, the equality was not so much equal as one would think. We had also elections. Everything was controlled. It would be a very difficult thing to vote for anyone not proposed by the communists. My best, most funny, or most strange elections was the -------. We had been marching, and we had to pick up the voting ballots, and without stopping we had to walk to the other side of the room and put the ballots in the voting booth. We could not change anything, we could not even admit it. And if there were problems, they just sent a group of soldiers who voted and changed the result. I don’t mean that it would be at that time possible that elections would work. Things were normal at the first side, but then something was behind which was somehow manipulated. D: Wow, that sound horrific! S: Well you wanted to have an interview so I should probably let you ask questions. D: Haha, no I’m glad you mentioned all of those things. I want to touch upon some of the things you mentioned later on, too. First of all, do you remember Prague Spring at all and the USSR and Warsaw Pact invasion? S: Yes, I remember that. One of the things that hits me is when I was a child, one of the first words I had written as a child was the word “democracy.” I had painted a box, and I remember that I had put there a big sign “democracy.” From which now I know that when 1967 came around Czech society started to change and be somehow allowed to say things that we had been thinking about. It was a big thing for a child who maybe only had 6 years. Then the second thing I remember of course some things that people were enthusiastic. During the communist era there was some manifestation that was more or less compulsory. But that year in 1968 on the first of May people were really happy to see their government. People were in a big queue and there was a manifestation for the government. And they wanted to. Two or three times. I was there, carried by my father. And I remember that. People were very enthusiastic. Then I remember the morning the soviet army. I went out of Prague for my eyes, it was a bit troubling because the best doctor was in Olomouc, so we started in the morning, and we had been going to the railway station in Moravia. And there someone told us “Where are you going, don’t you know that Prague has been overtaken by the Russians?” And we switched on the radio and, even though the radio station had already been blasted some people still found a way to broadcast. So sometimes they had been able to broadcast independent news. This is what I remember as a person. I also remember that we did not return to Prague when school started, so I started school in the village school. I remember when we returned to Prague, the Russian guns, Russian tanks, things destroyed by the tanks running over it. I remember a house who has left its roof and utmost floor by gunfire. And I remember things that had been destroyed and repaired, but you know if you have guns shooting into houses, you could repair it, but things would show up again. For example, the National Museum. We weren’t allowed to talk about how it was destroyed by guns, so we normally told and it was normal to say that pigeons destroyed it. Nobody believes that pigeons would destroy it. So that’s it. The other thing is that I went back to Prague when there was no more shooting so I didn’t see any dead people, but I have spoken to people who had seen dead people. So yes, although there had not been mass murders, there were gunshots. D: Did you personally know anyone who was killed? S: no, I was lucky that the range of shooting was not that big, at least in Prague. D: hmm, ok. Do you remember normalization and returning back into more censorship after the invasion? S: Yes, I remember it. It was quite strict. It started slowly but then it was quite fast. Also after the first year, there were protests in Prague, like one year after the invasion, with some shooting of guards against the protests and destroying aeroflot by the crowds and so on. I remember there was a ---for young people up to the ages of 8 years. I remember one was saved because two short young children who have some short memory. It was something like 50 years each. It has been so dangerous to the government and soviet army that all the people working there were changed. Two years later we had a teacher who taught us singing and works like that. Then he had used his words to create a song and he told us a song. Then we had another teacher. I still remember the song. One of the things I will never forget. D: So was he making fun of the soviet union? That’s why he was replaced? S: Yes. One of them was about a (technological glitch) that lives on the tree and it only said that he (technological glitch). Well in each street there was a number of the communist party who each year wrote something about you. You are doing well, putting out flags, etc. Generally they were very well educated and very strictly communists. Many times we would read something translated. It was very dangerous. As a child I could see that everyone was afraid. After some people being shot, after many people losing their jobs. I could see some soldiers. In many cases someone might say its only a temporary solution, but 22 years is not temporary. As a child, I could see this. I saw some other things. For example some of my classmates had parents who decided to leave the communist party and join the contra-revolution. We were told that in the school. As children we didn’t have to declare that we like it (communism). I was happy to take classes on foreign language. Luckily for me I started with English but the year later the students had to start with Russian, and then only learn English later. D: Do you remember you teachers having to publicly profess their trust in the Soviet Union? S: Yes, I remember all the teachers. We had a teacher who was responsible for class and she was also the head of the communist party at the school. And so she did often try to teach the good parts of the soviet union at the school. She taught us Russian meals, to know how to prepare them. It was difficult for me because it was hard to imagine how the food actually looked it. So she was a strange person because she actually believed in that. She finally resulted in the situation that she was not from the -----. She finished the year out with me but then after she could not find any job.And this was not because of her belief, but just she and her husband had been trying to get a better position among the communists so that was it. It was difficult, but yes. Some of the teachers proclaimed their love for the soviet union. Some of them really did that, most of them said that just to be able to be a teacher. D: That scary. You talked about earlier how in school you got bonus points if your school was part of the communist party. S: That was just for the admission. I could get excellent marks without having my parents be part of the communist party. D: Can you talk a little bit more about your education. You first had to work in the metros underground instead of going to the University. Was it difficult to pursue your degree? S: I went to the basic 9 years school which was what everybody did. I was lucky because I didn’t lose any time as far as getting my degree because I still took the entrance exams at the same time as my peers. But I just had less time to study because I was working in the metros. School was always available for people who were not afraid. Out of the 32 apprentices, there were about 20 cases of that kind-they could not study in secondary school because they were punished somehow by the communists. Sometimes I went to school to learn how to work and do labor, but the other days I went to work. In some manner I had less time to get my education, but I managed to finish going to the University. D: Oh ok that’s amazing. S: If I was one year younger, they would have accepted me to the secondary school because they did competitions. One year later, they issued a command that people who got first or second place in the competition must be excepted to study. The regime found that it had been a problem that these kids didn’t go to school. I have a strange story about the access to education. There had been people who were actively opposing the regime. Some of their children wanted to attend the university. And at the Czech Technical University, after the revolution, they released all of our files. And we found out that some people were expelled from the University for some reason. And some were not accepted. At that level, because the secret police on the entrance examination day, came to the University, this person was able to find the unwanted student, falsify his test, and interchange his test. And for three years this person was blocked from entering the university by this trick of the secret police. So if you were going to invent something, you could not invent it. D: Leading up to the Velvet Revolution, did you expect the fall of communism? S: I could not imagine that communism would fall down. I never wanted to enter the communist party because I didn’t like it, but I couldn’t imagine it ending. I was prepared for life that I wouldn’t be able to work anywhere in management and that it would be hard to study. At the end of my studies, someone in the University said that there would be a place for me at the University if I caved to the communist party, and the next day the place disappeared. You could chose, you could make it a career in the communist party, or you could survive. D: What were you doing the evening of the first protests of the Velvet Revolution? S: The first evening started with a student manifestation which was allowed ---When I arrived, it was really something which I had not been reading such stuff the whole life before. Somehow people had banners which was evident it was against the regime. One of the speakers was speaking so openly against the regime, that it was something which I couldn’t imagine. Then the students managed to get to the Wenceslas Square. At that time, I had to leave. I left and went to a different square-I did not know that people had been blocked and for some time many of them had been beaten. It was close to Wenceslas Square. After I went to the underground metro, I could not find anything, and so after a half-an-hour I went home. Then I listened to messages. The fact that there was no internet in the Czech Republic, although the internet was young. We listened to a broadcast from America. The broadcast from the Czech Republic was jammed so it was easier to receive the broadcast from America. D: Well it’s good you weren’t there when they started to beat up the people in the crowd. How did things change after the revolution? Did it happen suddenly? S: Well after two weeks, things changed drastically. We could say anything we wanted. The worst and first thing (during communism) was that family members would be punished. That was quite an effective means of resisting it and speaking openly. Well I was a scout leader. Well, scouts were forbidden at that time, so we were somehow surviving. There were some children who were actively protesting the regime. These are children. 8 years old. They were so dangerous, that when they went home from the meeting of the scouts they had two secret policemen walking with them. So you can imagine many people would be really afraid and not accept them to anything. My 5th scout group did accept people, knowing that sometimes our club room had some visitors. You know, it was that way. I understand that many people have been afraid just to talk with people under such communist supervision. D: ok. Continuing the discussion about the Velvet Revolution and the return to democracy, who was Vaclav Havel to you? S: Vaclav Havel was an excellent, outstanding person, a humanist, he was imprisoned several times by the communist government. And I think he did a big job in the beginning of Czechoslovakia and Czech Republic. D: Do you remember anyone you personally knew who stood up to communism? S: At first I knew the parents of those young guys in my scout group who were signing those anti-communist documents who were talking to radio America or Radio Free Europe. So I did know several such people. D: Today, 50 years after the Prague Spring invasion and close to 30 years after the fall of communism, what is life like, and do you still see the effects of communism in Czech people? S: Although you get freedom, you can’t wash everything down of you. There are still some things that originated during communism. Some people thinking that after all there were some people who had better times under communism than later. Yes, it is a long process, which is difficult to speed up. Although now we are close to a democracy, we still have some problems here. Second thing is that Czech Republic was one of the first (technologically advanced) countries before Soviet Union freed us from Hitler. For being a country who was extremely technologically advanced, we had not much advancement during communism so we fell down in the competition. The other thing is we also did not really have any money after the fall of communism. So this is a result which is not devastating but it’s here. D: In your work, have you ever encountered ex-communists? S: Yes, it wasn’t true before 1968, but after there was a big resistive place. After the 1968 some of the communist party decided that they would hire professors who didn’t even have to defend their dissertation. They have changed the numbers this way. Some had to leave because students didn’t like them. Some of them remain there. Some of them are still pretty important. We are currently fighting with some of them. D: Wow, that’s crazy. That’s all the questions I have today. Thank you so much for taking my call. S: Thank you. This is something that happens only once or twice in your life. It’s quite interesting to have lived during that time.  In January of 1968, Alexander Dubček was selected as the first secretary of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (KSC). At this time, Brezhnev, the leader of the USSR, trusted Dubček and allowed him to maintain power in Czechoslovakia. Brezhnev did not anticipate Dubček ’s democratic-leaning reforms. Soon following his assumption to power, Dubček attempted to decentralize the government and grant more rights and freedoms to the people. He coined this “socialism with a human face,” giving the cogs in the machine some liberty once again. Censorship stopped. Restrictions on media, speech, and travel were partially lifted, and the people experienced a brief breath of fresh air from the twenty some years of harsh oppression. Czechoslovakian films were some of the important, creative products of the Prague Spring, in which directors radically affected film styles around the world with their use of absurdity, humor, and critique of communism. Additionally, the Czech radio took advantage of the increase in freedom, and broadcasted anti-communist sentiments. This eventually made it a big target in the Prague Spring invasion. The USSR was not pleased with the growing freedom in Czechoslovakia. As Czechoslovakia was known as the connection between the East and the West, its leaning towards the West with growing freedoms and rights threatened communism in Europe. Brezhnev met with Dubček to try to stop the democratization of the country, and called him multiple times after, when Dubček hadn’t changed his policies. As a response to Dubček’s strong stance against censorship, some 650,000 men from Warsaw Pact troops, including soldiers from the Soviet Union, Bulgaria, Poland, and Hungary, invaded Czechoslovakia. They were coming to save Czechoslovakia from the evil West, from freedom. The invaders killed over 130 people in the immediate attack, leaving over 260 people seriously injured, and some 140 slightly injured. When the Warsaw troops entered Czechoslovakia on August 20th, they first had some trouble reaching Prague. Citizens in outside towns realized what was happening and went out to the streets to either fight or confuse the soldiers. Some painted over street signs, while others met the troops outside to fight. In Liberec, a small town to the north of Prague, citizens threw tomatoes and anything at hand at the tanks rolling in. Nine were killed here, some 45 seriously injured. The troops finally made it to Prague early morning on August 21. Here too, citizens met the tanks out in the streets. They tried to stop the tanks with makeshift barricades, even using their own bodies to form barriers on the roads. Some flipped military vehicles. The most violence happened in front of the radio building. Citizens tried to defend the building, and fought the troops back. Here, 17 were killed, but eventually a tank destroyed the radio building. Once the radio was down, it was easier to control the rest of Prague. Alexander Dubček and other politicians of importance were arrested, and sent back to Moscow for interrogations. They were forced to sign the “Brezhnev Doctrine,” and bring heavy censorship back to Czechoslovakia. The Warsaw troops were coming to help their brothers against the counter-revolution. Soldiers in the invading camps had been told that they were helping their brothers in Czechoslovakia against the dangerous revolutionaries-that they were there to rescue their friends. Tanks and censorship was their offering in friendship. After the invasion, the USSR set up the government in Prague, bringing back censorship in a period of what they called ‘normalization.’ At the onset of their new government, around 70,000 people fled the country, while more than 300,000 people left in later years. They were fleeing a killing machine. Perhaps the numbers of the invasion-less than 200 deaths, seems low for an invasion thus remembered. But, the invasion represents a much higher number of deaths. The re-implementation of Communism meant the snuffing out of freedom. It meant that people were no longer able to be people again; to have a conscience, think what they want, say what they think. It also meant physical death. According to Victims of Communism, the overall death toll of communism worldwide spans from 42,870,000 to 161,990,000. In Eastern Europe alone, communism is responsible for over 1,000,000 deaths. After Dubček was removed from office, Gustav Husák took his place as first secretary. He led the process of ‘normalization,’ restoring censorship, purging the political system of anti-communist sentiment, and strengthening the country’s ties with other socialist nations. Of the 115 members of the KSC Central Committee, Husák replaced 54. Throughout the nation, top levels of leadership were purged. According to the US Country Studies on the Czech Republic, professors, scientists, and social leaders who did not show full support of normalization lost their jobs and were forced to do menial work. Soviet control permeated Czechoslovakian government. In 1970, Czechoslovakia and the USSR signed the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation, and Mutual Assistance, in which Czechoslovakia lost sovereignty and allowed USSR to remain stationed in Czech lands. Soviet leaders kept a close watch of Czechoslovakian politicians. By January 1971, central authority was restored to its pre-Prague Spring level. Though communism permeated every facet of life, pro-freedom sentiments had not died completely among the people. Living in a thwarted environment forced some to find alternate avenues. Like a tree which twists and bends to find light in a shaded glen, leaders seeking freedom for themselves and their brothers found ways to pervade the communist haze. The most famous and celebrated spokesperson for civil rights and freedom, Vaclav Havel, continually searched for ways to undermine the communist regime. Born in a bourgeois family, Havel received a limited education (the communists didn’t like wealth and his dissident family, and wanted to punish success and opinions in many of their forms). This did not stunt his search for academic excellence and artistic expression. When he was 27, his first play, “Garden Party,” which highly criticized communism, premiered at the Prague Theatre in 1963. When Prague Spring was suppressed, he was forced to stop writing, and work as a manual labourer instead. However, this only added to Havel’s enthusiasm. He, among others, published Charter 77, a document in which listed the many civil rights violations of the communist party. This document, though confiscated in its original form, made its way into being published in the Western world, and broadcasted illegally to Czechoslovakians through Radio Free Europe and Voice of America. His efforts to bring down communism led to his imprisonment on multiple occasions. Yet, though he was imprisoned, the communists could not stop his message from spreading. Later, once out of jail, he founded the Civic Forum--a group made up of multiple anti-communist groups. With this, he lead the Velvet Revolution--a 10 day long protest which resulted in the toppling of communism in the Czech Republic. Vaclav Havel reminds us of our humanity--that each and every one of us has a unique conscience. That each is born with reason, and thus must exercise reason in his utmost capacity. That each and every one of us is born equal, and has the right to live, and exercise that equality in freedom of speech, opinion, and thought. He reminds us of who we are at the core, and who each has the capacity to become. Stay tuned to next week's post: an interview with an intellectual who was able to rise to the heights of academia despite being prohibited to study and do manual labor instead. Interesting links: https://www.victimsofcommunism.org/ http://blog.victimsofcommunism.org/victims-by-the-numbers/ http://www.getty.edu/museum/programs/performances/czech_films.html https://www.rferl.org/a/prague-spring-invasion-czech-soviet/29435069.html https://www.radio.cz/en/section/czech-history/the-1968-invasion-when-hope-was-crushed-by-soviet-tanks Prague Spring interviews https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QoIjNjAqH4k https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-XgxLgnpRYw  After I experienced the commemoration of Prague Spring, 1968 in the Czech Republic, my interest in the history of communism in this country peaked. One of my friends from class mentioned that she wanted to go to the Museum of Communism downtown, and I immediately asked to join. What I was about to learn would change my life. I had always known that communist governments were repressive. But, the extent to which they repressed their citizens was unknown to me. I had a fictional picture of communism in my mind: an Animal Farm-like reality in which nobody could trust anybody, wealth was extremely difficult to accumulate, and freedom was nonexistent. But, this fictional idea never was real to me. I imagined the real version of communism to be less harsh--that Czechoslovakia wasn’t repressed that much. I couldn’t have been further from the truth. Communism in Czechoslovakia was extreme. It robbed people of everything they had, including their consciences, personalities, and ability to trust. It made each person just a number in a system, forcing them to act as cogs in the machine rather than human beings. The following is what I learned at the museum: Although it wasn’t until after WWII when the Communist Party officially took control of the country, many citizens sympathized with communism in the early 1920’s. Leading up to the establishment of the Communist Party in the Czechoslovakian government in 1921, Czech lands suffered from droughts and poverty, and thus communism appeared to offer a solution to their problems. By 1928, the party had gained a substantial amount of followers, making it the second-largest party in the Communist International party. After WWII, the USSR dictated the government in Czechoslovakia. Socialist parties were abolished, and the Communist party gained control. Once in control, the Communist Party leaders initiated massive eradications of dissenters. At the start of Communist control in Czechoslovakia, 23,000 people were found guilty of crimes. Of the 23,000, 713 were sentenced to death immediately. In 1945, 75% of industry was in the government’s control, and in 1948, the government put to use the taking of others’ property, or “legalized theft.” Although Klement Gottwald was the president of Czechoslovakia, he had limited control himself. Most of the decisions were dictated to him from the USSR. Thus started what the Museum of Communism calls the “Communist Dictatorship.” From 1948-1968, Czechoslovakia was subject to extreme poverty, doctrination, and oppressive control. The Communists created a new ideal for their citizens: Homo Communism. The new socialist man was the laborer. He volunteered for his community, loved the army, and waved the soviet union flag. To showcase this ideal, the government created many banners and paintings glorifying Homo Communism, including the huge painting attached at the bottom of this article. Because labor was valued so much, and because the Communists in Czechoslovakia thought that the bulk of the community relied on physical labor, the government sponsored many uranium mines. Working in these plants was extremely unhealthy, and the stress of gathering uranium left huge environmental issues in the country, as well as economic. To compensate for the government’s overinvesting in industry, it decided to change the value of its currency overnight and lower its debts. Although a few days before doing so government leaders promised that the money value would not change, they changed the value regardless on June 1, 1953. Imagine going to bed with $50,000 dollars in your bank account, to wake up to only $1,000. The reform made paupers out of the citizens, while it decreased the debt of an extremely inefficient government system. Cash lost about 80% of its value. The West referred to this reform as the “great swindle,” which it surely was. 130 anti-communist strikes occurred as a result of the reform, to which the government acted violently to repress. Additionally to the Homo Communism ideal, and all of the problems it brought with it, communism hacked away at Czech culture. Baby Jesus, who traditionally brings presents on Christmas Eve, was replaced by Grandfather Frost. The Scout program--an important extracurricular program for many Czechs--was replaced with the Pionyr program. The Communists tried desperately to thwart religious practices. Many faithful Catholics could not hold jobs where they had the possibility of affecting the culture. Among many Catholics thus persecuted, Dr. Radomir Maly, a former historian for a museum in the town of Kromeriz, was forced to quit his job and work as a menial worker because he would have had too strong of a religious effect on those around him. Dr. Maly’s story of persecution is a common one for faithful Christians in Czechoslovakia; from 1948 to 1968, the number of priests in the country decreased in half. Many practicing Christians were forced to either stop practicing their religion, or turn to illegal, underground meetings. The persecution of Christians has a lasting effect in Czech Republic. In 1921, about 82% of Czechs identified as Roman Catholic, but by 2011 only 10% of Czechs identified as Roman Catholic. The Communist policies were bad. Taking away freedom anywhere is a violation of human rights. But the ways in which they were enforced are close to unimaginable. The StB was the Czechoslovakian secret police who monitored their neighbors all while remaining under cover of ordinary citizens. StB infiltrated all parts of life. In every avenue of work, members of the StB monitored their neighbors and coworkers. StB kept records of the people they watched. They listened in on phone conversations at switchboards, bugged rooms, and set up secret cameras. If these records hadn’t been burnt, they would have covered several soccer fields, piled a few meters high. In the 1950’s, 422 labor camps were created, in which lived 11,026 residents. Dissidents and non-dissidents alike of the ‘Communist Dictatorship’ were systematically placed in these camps. The Ministry of Justice predetermined how many people they wanted to imprison. Thus, many of the imprisoned had not been loud dissidents of communism, and some hadn’t even committed any crimes. The StB had two rules regarding the placement of people into the prison camps: 1. The people arrested were the only witnesses to their crimes, and 2. The StB could never free someone they arrested. Breaking any of these rules would undermine the StB authority. The StB had several ways of forcing confessions out of their imprisoned: they would torture the arrested by not allowing them to sleep well, waking them every 15 minutes from their cells, they would beat them up physically, inject drugs into their systems, and not let them live until they forced a confession. Travel was hardly an option for Czechoslovakians. Either they travelled to the West illegally (and never returned), or they travelled to the USSR on highly supervised trips. When Czechoslovakians visited the USSR, KGB was vigilant in never letting its visitors see the true face of communism. Escape from Czechoslovakia into Western countries was nearly impossible. Huge barriers and barbed wire fences were built along the borders, and sand plains led up to the barriers to highlight the dark bodies trying to escape against the white sand. Many were killed while trying to escape. Communism was indoctrinated in schools. Children were taught to tell on their parents if their parents ever talked poorly of communism. My grandmother, who grew up in communist Prague, said that she had to be very careful with what she told her children. She admits though, that her children were smart and knew not to say anything, and that most of the other children understood not to talk about communism, too. Additionally, children were taught that wealth was evil. If someone acquired wealth, they were against the common man. The subject of their education was likewise made up of propaganda. For example, children had to write essays on the benefits of their liberators, the Soviet Union. Undoubtedly, if they questioned the essay prompt, or the USSR, they were met with grave repercussions. Thus, Czechoslovakians lived very tough lives. Their commemoration of Prague Spring, 1968 weighs much more when seen with the knowledge of what Czechoslovakians were trying to escape. The goal of the commemorative movement--that the nightmares never go grey--was met with me. The commemoration made me interested in Czechoslovakian history, and made me question my previous knowledge. Now that I know this “Communist Dictatorship” started with the approval of the people, I will be much more skeptical about politicians in my own country, and vigilant that none try to take away my freedom. I hope that learning about communism in Czechoslovakia has the same effect on you, too. Stay tuned for the second part: Prague Spring 1968-Post Communism Read more here: -https://www.catholicworldreport.com/2017/05/19/catholics-in-communist-czechoslovakia-a-story-of-persecution-and-perseverance/ -http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/country_profiles/1844842.stm  This past August 21, the world, especially Czech Republic, commemorated the 50th anniversary of the Prague Spring invasion. Various speakers spoke against the evils of communism, and how the Prague Spring invasion from the USSR and other Warsaw Pact troops threw the nation back into darkness. Luckily for me, I was in Prague in August, receiving my TEFL certificate, and was able to witness many of the commemorations of this pivotal point in Czech history. In 1968, Czechoslovakia experienced a brief period of liberation and artistic creation, called Prague Spring. Coined by then president Alexander Dubcek as “socialism with a human face,” Czech society loosened from a previously oppressive and completely socialized society. Czechoslovakia experienced a burst in creation, giving this time period its name, “Zlata sedesata” (the golden sixties). But, upset with the direction Czechoslovakia was headed in, and wary the country--as seen by many as the connection between East and West Europe--would inspire other countries to adopt looser communist governments, troops from the USSR, ordered by stalinist president Antonin Novotny, along with other Warsaw Pact countries, rolled through Czechoslovakia and re-instated strict communism. All in all, around 250,000 troops invaded Czechoslovakia, including some 6,300 tanks and 250 airplanes. Around 72 Czechs and Slovaks were killed during the invasion, and some 270 injured. Although the numbers may seem low for something commemorated as such, the invasion symbolizes the loss of freedom and the catalyst of many more deaths during the 'normalization' back into the Communist way of life. During the week leading up to the Tuesday, many of the historic locations in Prague housed special events to honor the lives lost in the reoccupation of Czechoslovakia. In Wenceslas Square, where citizens--typically students--historically protested, and where Warsaw tanks famously fired at the Radio station during the reoccupation, several organizations, including Vojenský Historický Ústav Praha and others, sponsored the showing of documentaries on a blow-up screen, posters displaying images of the brutal invasion, speakers, and singers. The goal of the commemoration was twofold: to remember the victims of Communism, and to make sure that Communism and similar ideologies never return. Their logo reflects their goal: “Aby sny nezešedly” (Let not the dreams (read "nightmares") go grey). On Tuesday, August 21, many important locations had commemorations. A concert, organized by Czech Radio, was held in Wenceslas square, where many songs about the invasion were sung. A special video and maps were projected onto the National Museum nearby. Various museums had special exhibits on the invasion, free to the public on Tuesday. In addition, in Kampa, a grassy, tranquil area by the Vltava river, several speakers recounted the events of the haunting day. About 300 melancholic people, holding Czech flags and banners, surrounded a small stage which held three speakers. Among them, a USSR expatriate Mr. Gorbanevska spoke against the ignorance of Communism. Gorbanevska’s family has a detailed history with Communism. The repression of Prague Spring happened when he was young, and living in Russia at the time. His mother Natalya Gorbanevskaya, a strong proponent of freedom, and vocalist against the USSR, was one of the eight people who protested on the Red Square in Moscow several days after the Prague Spring invasion. She brought young Gorbanevska with her, as well as her two other children. All eight protestors were swept up by the KGB within seven minutes of sitting in the square with a Czechoslovakian flag and a banner which read things such as: “мы теряем лучших друзей” (We are losing our best friends), “Ať žije svobodné a nezávislé Československo“ (Long live free and independent Czechoslovakia), and “Позор оккупантам!” (Shame to the occupiers). Most of the seven were subject to harsh treatment, including Gorbanevska’s mother, who was later sent to a psychiatric hospital for being a dissident, diagnosed with “sluggish schizophrenia.” She has been celebrated as a hero in the West, and is well-known for her numerous acts of courage and literary works on the necessity of freedom. At the talk, Gorbanevska humbly opened his speech in a highly accented Czech, saying “Odpust mi, nemluvim Cesky” (Forgive me, I don’t speak Czech). A translator stood by his side and translated his Russian into Czech for the younger people in the crowd. For a people who had to learn Russian under the occupation, hearing Russian would be a hard thing on such a day. Gorbanevsky’s opener, however, created a platform on which he and the Czechs listening could together mourn the invasion. He continued to say, “I wanted to share a few words. A normal person to normal people.” Gorbanevsky’s message was brief and direct: we must never forget the atrocities of Communism, and must actively reject it in all of its future forms. He dwells on current Russians’ ignorance of the repression, and how refusing to learn about the evils of the USSR based on the fact that these events took place in the past is an unforgivable excuse. If we forget the history of Communism--how it first started out as a political party which gained much popularity but evolved into a soul-killing machine--we risk repeating it. In his talk, he chastises the Czech president, Miloš Zeman, for his weak stance against the Communist party in the Czech Republic. To the mention of Zeman, a rustling went through the crowd, stirring everyone a brief period of whistling in disapproval of Zeman. They’d been stabbed in the back by the secret police, their own brothers, countless times during Communist occupation. Betrayal by their president is close to unbearable. Gorbanevsky concluded his speech by encouraging the crowd to never forget the tanks rolling into Prague, and to never tolerate limitations of freedom. He encouraged everyone in the crowd to continue protesting injustice everywhere, even if they risk persecution. Protesting evil is the right thing to do. Following Gorbanevsky’s speech, the founder of the “The Memory of a Nation” project, a non-profit organization, talked about his work in sharing stories of normal people’s lives under Communism. His work has the same goal as those who organized commemorations throughout Prague--that people should never forget Communism, and never stop fighting for freedom. After all of the speakers held the stage, a young singer was called to the stage. She sang the Czech national anthem, “Kde domov muy” (Where my home is), and the whole crowd joined. Following the song, members of the crowd lit candles for people they knew who died at the hands of the Communists during the occupation (the intellectuals, celebrities, and politicians who wouldn’t promote the USSR, as well as many others). They processed from Kampa to the statues memorializing the enemies of the state, and lay the candles at the feet of the statues. At the statue’s side, a scout (Scouts had been outlawed under Communism) held up the Czech flag. People reverently placed their candles down by the statues, and quietly related their stories to their neighbors. This experience taught me many things. It explained the quiet stillness in the crowded metros, and the hard, emotionless face of the passersby. Communism may be gone in the Czech Republic, but its effects still linger. We must never forget what Communism was, and how it came to be here, but we also must be willing to move on and trust others again, rejoice, and enjoy this life. Stay tuned for my impression and recap of the Museum of Communism next. Interesting links for follow-up research: -http://www.vzpominka1968.cz/cz/s1193/c2863-Rocnik-2018 -http://www.pametnaroda.cz/ -https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e12rGRO4JuA  John Milton was a famous 17th century poet. He is most famous for his epic, Paradise Lost, but he also wrote many brilliant shorter poems in preparation. From his Familiar Letters, we know that he felt called to write this epic, but that he hadn’t yet felt prepared enough to write about the Fall of Man. Through writing shorter poetry, he determined that he would be ready for his great work, and arguably one of the greatest works in British history. One of Milton’s common themes to his writing is the importance of the transcendence. This idea, which has been explained by many thinkers and Church Fathers, has shaped the Liberal Arts. Through believing in something which transcends pastoral reality, people have a basis for forming their arguments. In seeing that the things of the earth fades, it is easy to see the validity in Milton’s claim that there must be something which transcends that which fades. Milton argues that people should focus on the things which transcend, such as God and soul, rather than things which ultimately will not have importance, such as earthly goods and fame. Milton was not the first to argue this viewpoint. Many of the philosophers of antiquity argued this idea. In the Phaedo, Plato responds to questions for his lack of fearing death by simply stating that it is in the office of the philosopher to consider the afterlife, and ponder death, thereby preparing himself for death. By the time death comes, he should be well prepared in thought by philosophizing his whole life. While Plato believed in a different vision of the soul than Christians like Milton, he was right to focus on things eternal than mortal. Further along in Western Tradition, Church leaders discussed the right treatment of earthly goods. St. Augustine of Hippo famously wrote about ordinate desires, and the hierarchy of goods. In St. Augustine’s Confessions, Augustine argues that everything is good in its order. For example, Love is good and from God, but when human love is placed about the love of God, through various means, it is tinted and becomes sinful. This applies to other goods, such as food or earthly possessions. God gave humans food and earthly things so that we can survive, but when these objects are placed above God, they too become distractions from the Good and therefore are not good anymore. Milton builds on the argument of the powerful eternal glory over earthly goods through his rich poetry. Many of Milton’s poems allude to the great thinkers of the past, and enhance their arguments with iambic pentameter, or blank verse. He argues that mirth is a means for us to live, but he chooses melancholy. He uses light and darkness to highlight the Truth in God and the lies in the devil or inordinate desire. And he describes Jesus as a powerful yet merciful savior. A few of my favorite poems are On the Morning of Christ’s Nativity, L’Allegro and Il Penseroso, and On Shakespeare.  This week, my friend and I went to the Royal Monastery of Santa Maria in Poblet, Tarragona. This monastery, which was only about a half an hour drive from Tarragona, was spectacular. The whole drive to the monastery set up grand expectations for the monastery itself, and they were met and exceeded. From the outside, the monastery did not seem large at all, but after passing through the surrounding walls, we were surprised by the size of the monastery. Large walkways, tall ceilings, and tall and thick walls brings to attention the beautiful Romanesque architecture. But, instead of being decorated in a really ornate way, the builders of the monastery had focused on simplicity, so as to not create a distraction for the studious monks. It was in this simplicity, however, which demonstrated beauty. In 1150, the monastery was founded by monks of the Benedictine order. This monastery is one out the three Cistercian monasteries which belonged to the Crown of Aragon. While we took a tour in the monastery, we were surprised to see the tombs of many of the Kings and Queens of Aragon in the church. The remains of Edmundo de la Croix, Alfonso V of Aragon, Enrique de Trastamara, Martin I of Aragon, Francisco Roures (archbishop of Tarragona), Juana of Aragon, the children of Pedro IV, and other children can be found in tombs in two arches in the church, among others. On the outside of these tombs, sculptors designed full-life images of them, to remind the public of who had been buried there. During our tour, we noticed that some of the statues were damaged, while others looked like they were unblemished. The tour guide told us that in 1835, the Prime Minister during the rule of Isabella II, Mendizabal, ordered the closing of all of the monasteries in Spain, and opening the land up to the public. The added property was seen as a source of wealth to the country because the monasteries were not compensated for their loss, but this decision just ended up in vandalism to the monasteries with heartbreaking loss to paintings and other valuables. In 1935, the land was returned back to the church. And in 1940, Italian monks of the same order came and reoccupied it. Ever since the reopening of the monastery, the monks have been working to replace the stolen and broken pieces. Now, the monks work and study throughout the day. The monastery is the home to twenty-seven professed monks, one oblate, two novices, and one familiar. Throughout our visit, I was in awe of all of the rich history of the monastery. The silence and tranquility helped make the experience a peaceful and meditative one. I couldn’t help but envy the monks in their peaceful study environment, away from all of the noise of the world, but still in contact with other people and visitors. I’m sure I will take back some of the things I learned from this visit, and value moments of silence in the future.  In the south of Catalonia, many people would recognize Salou right away. During spring break, many tourists from England come and party the entire week at the elite clubs in this city. They totally embrace the Spanish schedule of staying and waking up late. In addition, in the summer, the beaches are packed with sunburnt tourists, leaving behind trash and other unwanted pollutants in the water. Even though this city does have appeal (there are many nice cafes on the sand by the water, and there are many good restaurants), just one city down along the coast hosts a calmer, and I’d argue better, experience. Cambrils, a city with great camping spots near the sea, clean beaches with at least some waves, and a family friendly downtown area, among other things, is sure to paint a better picture of Spain. With more locals enjoying the many beaches, you will be sure to get a more accurate representation of Catalonia’s unique culture. Cambrils has a great appeal for active people. With many water sports available along the coast, you can enjoy the sea and workout at the same time. There are places to rent kayaks, wind surf, paddle board, and parasail. In addition, many of the large sidewalks have bike lanes, and these are always used. In the mornings and afternoons, plenty of runners run alongside the paths. If you want a vacation filled with relaxation, the downtown area is perfect. You can go shopping in the many clothing, jewelry, and shoes stores. During the summer, these stores put out their summer clothes on sale so that many of the tourists buy many clothes. Also, like Salou, you can find plenty of good restaurants. In the downtown area, restaurants line the sidewalks. In the evenings, families and friends dine in the outdoor areas of these restaurants, with a view of the ships in the port. After dinner, you can have dessert at the many ice-cream places, gofre restaurants (a really good type of waffle), or creperias. Besides sports, the beach, and restaurants, Cambrils has some rich history as well. In the city, there are old Roman buildings. In addition, there is an old watch tower set up in the middle of the port, which was built in the 17th century to keep watch over pirates. The last pirate attack was in 1799, and the tower right now forms a part of the Cambrils History Museum. If you are looking for a tranquil, family-friendly place to relax, I highly recommend visiting Cambrils!

|

Jessica De GreeJessica teaches 5th grade English and History as well as 11th grade Spanish III at a Great Hearts Academy in Glendale, AZ. In addition to teaching, she coaches JV girls basketball and is a writing tutor for The Classical Historian Online Academy. Jessica recently played basketball professionally in Tarragona, Spain, where she taught English ESL and tutored Classical Historian writing students. In 2018, she received her Bachelor's degree in English and Spanish from Hillsdale College, MI. Archives

April 2020

Categories

All

|

|

SUPPORT

|

RESOURCES

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed