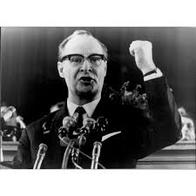

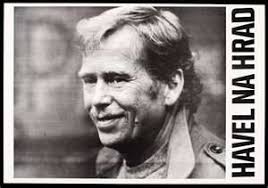

In January of 1968, Alexander Dubček was selected as the first secretary of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (KSC). At this time, Brezhnev, the leader of the USSR, trusted Dubček and allowed him to maintain power in Czechoslovakia. Brezhnev did not anticipate Dubček ’s democratic-leaning reforms. Soon following his assumption to power, Dubček attempted to decentralize the government and grant more rights and freedoms to the people. He coined this “socialism with a human face,” giving the cogs in the machine some liberty once again. Censorship stopped. Restrictions on media, speech, and travel were partially lifted, and the people experienced a brief breath of fresh air from the twenty some years of harsh oppression. Czechoslovakian films were some of the important, creative products of the Prague Spring, in which directors radically affected film styles around the world with their use of absurdity, humor, and critique of communism. Additionally, the Czech radio took advantage of the increase in freedom, and broadcasted anti-communist sentiments. This eventually made it a big target in the Prague Spring invasion. The USSR was not pleased with the growing freedom in Czechoslovakia. As Czechoslovakia was known as the connection between the East and the West, its leaning towards the West with growing freedoms and rights threatened communism in Europe. Brezhnev met with Dubček to try to stop the democratization of the country, and called him multiple times after, when Dubček hadn’t changed his policies. As a response to Dubček’s strong stance against censorship, some 650,000 men from Warsaw Pact troops, including soldiers from the Soviet Union, Bulgaria, Poland, and Hungary, invaded Czechoslovakia. They were coming to save Czechoslovakia from the evil West, from freedom. The invaders killed over 130 people in the immediate attack, leaving over 260 people seriously injured, and some 140 slightly injured. When the Warsaw troops entered Czechoslovakia on August 20th, they first had some trouble reaching Prague. Citizens in outside towns realized what was happening and went out to the streets to either fight or confuse the soldiers. Some painted over street signs, while others met the troops outside to fight. In Liberec, a small town to the north of Prague, citizens threw tomatoes and anything at hand at the tanks rolling in. Nine were killed here, some 45 seriously injured. The troops finally made it to Prague early morning on August 21. Here too, citizens met the tanks out in the streets. They tried to stop the tanks with makeshift barricades, even using their own bodies to form barriers on the roads. Some flipped military vehicles. The most violence happened in front of the radio building. Citizens tried to defend the building, and fought the troops back. Here, 17 were killed, but eventually a tank destroyed the radio building. Once the radio was down, it was easier to control the rest of Prague. Alexander Dubček and other politicians of importance were arrested, and sent back to Moscow for interrogations. They were forced to sign the “Brezhnev Doctrine,” and bring heavy censorship back to Czechoslovakia. The Warsaw troops were coming to help their brothers against the counter-revolution. Soldiers in the invading camps had been told that they were helping their brothers in Czechoslovakia against the dangerous revolutionaries-that they were there to rescue their friends. Tanks and censorship was their offering in friendship. After the invasion, the USSR set up the government in Prague, bringing back censorship in a period of what they called ‘normalization.’ At the onset of their new government, around 70,000 people fled the country, while more than 300,000 people left in later years. They were fleeing a killing machine. Perhaps the numbers of the invasion-less than 200 deaths, seems low for an invasion thus remembered. But, the invasion represents a much higher number of deaths. The re-implementation of Communism meant the snuffing out of freedom. It meant that people were no longer able to be people again; to have a conscience, think what they want, say what they think. It also meant physical death. According to Victims of Communism, the overall death toll of communism worldwide spans from 42,870,000 to 161,990,000. In Eastern Europe alone, communism is responsible for over 1,000,000 deaths. After Dubček was removed from office, Gustav Husák took his place as first secretary. He led the process of ‘normalization,’ restoring censorship, purging the political system of anti-communist sentiment, and strengthening the country’s ties with other socialist nations. Of the 115 members of the KSC Central Committee, Husák replaced 54. Throughout the nation, top levels of leadership were purged. According to the US Country Studies on the Czech Republic, professors, scientists, and social leaders who did not show full support of normalization lost their jobs and were forced to do menial work. Soviet control permeated Czechoslovakian government. In 1970, Czechoslovakia and the USSR signed the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation, and Mutual Assistance, in which Czechoslovakia lost sovereignty and allowed USSR to remain stationed in Czech lands. Soviet leaders kept a close watch of Czechoslovakian politicians. By January 1971, central authority was restored to its pre-Prague Spring level. Though communism permeated every facet of life, pro-freedom sentiments had not died completely among the people. Living in a thwarted environment forced some to find alternate avenues. Like a tree which twists and bends to find light in a shaded glen, leaders seeking freedom for themselves and their brothers found ways to pervade the communist haze. The most famous and celebrated spokesperson for civil rights and freedom, Vaclav Havel, continually searched for ways to undermine the communist regime. Born in a bourgeois family, Havel received a limited education (the communists didn’t like wealth and his dissident family, and wanted to punish success and opinions in many of their forms). This did not stunt his search for academic excellence and artistic expression. When he was 27, his first play, “Garden Party,” which highly criticized communism, premiered at the Prague Theatre in 1963. When Prague Spring was suppressed, he was forced to stop writing, and work as a manual labourer instead. However, this only added to Havel’s enthusiasm. He, among others, published Charter 77, a document in which listed the many civil rights violations of the communist party. This document, though confiscated in its original form, made its way into being published in the Western world, and broadcasted illegally to Czechoslovakians through Radio Free Europe and Voice of America. His efforts to bring down communism led to his imprisonment on multiple occasions. Yet, though he was imprisoned, the communists could not stop his message from spreading. Later, once out of jail, he founded the Civic Forum--a group made up of multiple anti-communist groups. With this, he lead the Velvet Revolution--a 10 day long protest which resulted in the toppling of communism in the Czech Republic. Vaclav Havel reminds us of our humanity--that each and every one of us has a unique conscience. That each is born with reason, and thus must exercise reason in his utmost capacity. That each and every one of us is born equal, and has the right to live, and exercise that equality in freedom of speech, opinion, and thought. He reminds us of who we are at the core, and who each has the capacity to become. Stay tuned to next week's post: an interview with an intellectual who was able to rise to the heights of academia despite being prohibited to study and do manual labor instead. Interesting links: https://www.victimsofcommunism.org/ http://blog.victimsofcommunism.org/victims-by-the-numbers/ http://www.getty.edu/museum/programs/performances/czech_films.html https://www.rferl.org/a/prague-spring-invasion-czech-soviet/29435069.html https://www.radio.cz/en/section/czech-history/the-1968-invasion-when-hope-was-crushed-by-soviet-tanks Prague Spring interviews https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QoIjNjAqH4k https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-XgxLgnpRYw

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Jessica De GreeJessica teaches 5th grade English and History as well as 11th grade Spanish III at a Great Hearts Academy in Glendale, AZ. In addition to teaching, she coaches JV girls basketball and is a writing tutor for The Classical Historian Online Academy. Jessica recently played basketball professionally in Tarragona, Spain, where she taught English ESL and tutored Classical Historian writing students. In 2018, she received her Bachelor's degree in English and Spanish from Hillsdale College, MI. Archives

April 2020

Categories

All

|

|

SUPPORT

|

RESOURCES

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed