|

Dr. Zbynek Skvor grew up in Czechoslovakia during communism. He was born in the early 1960s, and has experienced many of the different phases of communism in the country, including a brief period of liberalization during the Prague Spring, the communist's strict reinforcement of censorship during the 'normalization' period succeeding the Prague Spring invasion in 1968, the Velvet Revolution, and the democratization of the country once freed from communism's grip. His story is an inspiring one. When he was a little child, he went to celebrate Dubcek's more liberal government in his father's arms. One of the first words he wrote was "Democracy." Later, not allowed to continue his studies in secondary school, he was forced to work in the underground metro system. Nonetheless, he pursued his love of Electromagnetism and found a way to study. Now, he is the Department Chair of Electromagnetic Fields at the Czech Technological University in Prague, along as the Vice-Rector for Scientific Research and Creative Activities and the head of the Vice-Rector's office for Scientific Research Activities. Today, close to 30 years after the fall of communism, he deals with ex-communists on a daily basis.

D: I have with me the head of Vice-Rector’s Office for Scientific Research activities at the Czech Technological University in Prague, the Vice-Rector for science and creative activities and PhD studies, the department chair of Electromagnetic Field studies, and my uncle, Zbynek Skor. He was born in the early 1960s in Czechoslovakia, putting him at around 8 years old during the Prague Spring Invasion and grew up during the normalization period in Czechoslovakia post-Prague Spring invasion. Thank you for joining me today. To start off, what was everyday life like under communism? S: Well that’s difficult to tell in a few sentences. First, everyday life means that you have to get food, get some place to live, if you would like to raise your children, you would like to get them educated, and some entertainment. And all of that was somehow possible, but all of that was somehow difficult. For example, Czech Republic was quite lucky in the fact that it had enough food in the shops. That does not mean that you could buy meat everyday. There was some meat, but not good meat. There was one day a week and then you had to queue. But they were short queues like 20 minutes. And you could get the meat. And you could get other things. There have been some countries which the situation was quite different. But, Czech Republic was lucky. We had enough potatoes. There were no bananas or oranges, but you could live without bananas and oranges. Of course, sometimes if something was missing in the markets, like toilet paper, for example. Then you had to queue because you could only buy two rolls per person. Of course, this would consume so much of your time. Then sometimes you had to queue if you wanted a bed. You had to queue several times. But it was probable that sometime the bed would arrive. And after queuing several hours in the queue several times, and sometimes queuing overnight, you were in the position to get a bed. Of course this system had consequences, like slowing down your work. But you still could get along with. Of course there were people who were privileged who didn’t have to queue because they were somehow well established in the system. There were some people who had better access to medical care than others, although officially everything was, every person in the republic was equal to another person. But for example, you wanted to raise your children and get them educated. The worst things that were before, at the beginning of socialism, at the beginning there were some people who could not study at any case. For example there were some people who have sinned by having their parents own a shop. Although it still was somehow terrible. There have been real entrance exams which had 100 points for maximum. In my case when I wanted to enter secondary school, like high school in the US. If a parent was a communist, you had 10 points more, if both parents were communists you had 20 points more. But you could still get there. Unless there were some exception. Sometimes it could happen where some of your relatives said something that was incoherent with the regime. You would never find out what they did, but you were never admitted. For example, I wanted to study at gymnasium, the classic secondary school, but somehow it did not work. So finally I got skilled and I repaired the underground cars in Prague. The metro. That was my primary education. I somehow managed to get to the University. But others did not. It was quite funny. For example, when I was getting skilled for repairing the metro cars, for the whole time we were sitting in the classroom. My colleague on my left hand side was Ladislav Medved. And his family was, by the way he got a secondary degree in mechanical engineering, but anyway he was from Plzen. In Plzen he could not even get an apprenticeship. And that was because his father in 1968 was responsible for the newspaper in Plzen. He printed there, it’s difficult to say in English. The word for a big gun and an artistic picture is the same. So he had printed in the newspaper a picture with the caption of this is a collection of soviet arts, and the guns were the picture. So after this neither he, his family, although he loved the work in the newspaper, his son or daughter could not get educated in Plzen. Fortunately in Prague there was two places where a professor, although communist, took the risk to educate those people. By the way today he works with the newspaper in Plzen again. Although formerly everybody was equal, the equality was not so much equal as one would think. We had also elections. Everything was controlled. It would be a very difficult thing to vote for anyone not proposed by the communists. My best, most funny, or most strange elections was the -------. We had been marching, and we had to pick up the voting ballots, and without stopping we had to walk to the other side of the room and put the ballots in the voting booth. We could not change anything, we could not even admit it. And if there were problems, they just sent a group of soldiers who voted and changed the result. I don’t mean that it would be at that time possible that elections would work. Things were normal at the first side, but then something was behind which was somehow manipulated. D: Wow, that sound horrific! S: Well you wanted to have an interview so I should probably let you ask questions. D: Haha, no I’m glad you mentioned all of those things. I want to touch upon some of the things you mentioned later on, too. First of all, do you remember Prague Spring at all and the USSR and Warsaw Pact invasion? S: Yes, I remember that. One of the things that hits me is when I was a child, one of the first words I had written as a child was the word “democracy.” I had painted a box, and I remember that I had put there a big sign “democracy.” From which now I know that when 1967 came around Czech society started to change and be somehow allowed to say things that we had been thinking about. It was a big thing for a child who maybe only had 6 years. Then the second thing I remember of course some things that people were enthusiastic. During the communist era there was some manifestation that was more or less compulsory. But that year in 1968 on the first of May people were really happy to see their government. People were in a big queue and there was a manifestation for the government. And they wanted to. Two or three times. I was there, carried by my father. And I remember that. People were very enthusiastic. Then I remember the morning the soviet army. I went out of Prague for my eyes, it was a bit troubling because the best doctor was in Olomouc, so we started in the morning, and we had been going to the railway station in Moravia. And there someone told us “Where are you going, don’t you know that Prague has been overtaken by the Russians?” And we switched on the radio and, even though the radio station had already been blasted some people still found a way to broadcast. So sometimes they had been able to broadcast independent news. This is what I remember as a person. I also remember that we did not return to Prague when school started, so I started school in the village school. I remember when we returned to Prague, the Russian guns, Russian tanks, things destroyed by the tanks running over it. I remember a house who has left its roof and utmost floor by gunfire. And I remember things that had been destroyed and repaired, but you know if you have guns shooting into houses, you could repair it, but things would show up again. For example, the National Museum. We weren’t allowed to talk about how it was destroyed by guns, so we normally told and it was normal to say that pigeons destroyed it. Nobody believes that pigeons would destroy it. So that’s it. The other thing is that I went back to Prague when there was no more shooting so I didn’t see any dead people, but I have spoken to people who had seen dead people. So yes, although there had not been mass murders, there were gunshots. D: Did you personally know anyone who was killed? S: no, I was lucky that the range of shooting was not that big, at least in Prague. D: hmm, ok. Do you remember normalization and returning back into more censorship after the invasion? S: Yes, I remember it. It was quite strict. It started slowly but then it was quite fast. Also after the first year, there were protests in Prague, like one year after the invasion, with some shooting of guards against the protests and destroying aeroflot by the crowds and so on. I remember there was a ---for young people up to the ages of 8 years. I remember one was saved because two short young children who have some short memory. It was something like 50 years each. It has been so dangerous to the government and soviet army that all the people working there were changed. Two years later we had a teacher who taught us singing and works like that. Then he had used his words to create a song and he told us a song. Then we had another teacher. I still remember the song. One of the things I will never forget. D: So was he making fun of the soviet union? That’s why he was replaced? S: Yes. One of them was about a (technological glitch) that lives on the tree and it only said that he (technological glitch). Well in each street there was a number of the communist party who each year wrote something about you. You are doing well, putting out flags, etc. Generally they were very well educated and very strictly communists. Many times we would read something translated. It was very dangerous. As a child I could see that everyone was afraid. After some people being shot, after many people losing their jobs. I could see some soldiers. In many cases someone might say its only a temporary solution, but 22 years is not temporary. As a child, I could see this. I saw some other things. For example some of my classmates had parents who decided to leave the communist party and join the contra-revolution. We were told that in the school. As children we didn’t have to declare that we like it (communism). I was happy to take classes on foreign language. Luckily for me I started with English but the year later the students had to start with Russian, and then only learn English later. D: Do you remember you teachers having to publicly profess their trust in the Soviet Union? S: Yes, I remember all the teachers. We had a teacher who was responsible for class and she was also the head of the communist party at the school. And so she did often try to teach the good parts of the soviet union at the school. She taught us Russian meals, to know how to prepare them. It was difficult for me because it was hard to imagine how the food actually looked it. So she was a strange person because she actually believed in that. She finally resulted in the situation that she was not from the -----. She finished the year out with me but then after she could not find any job.And this was not because of her belief, but just she and her husband had been trying to get a better position among the communists so that was it. It was difficult, but yes. Some of the teachers proclaimed their love for the soviet union. Some of them really did that, most of them said that just to be able to be a teacher. D: That scary. You talked about earlier how in school you got bonus points if your school was part of the communist party. S: That was just for the admission. I could get excellent marks without having my parents be part of the communist party. D: Can you talk a little bit more about your education. You first had to work in the metros underground instead of going to the University. Was it difficult to pursue your degree? S: I went to the basic 9 years school which was what everybody did. I was lucky because I didn’t lose any time as far as getting my degree because I still took the entrance exams at the same time as my peers. But I just had less time to study because I was working in the metros. School was always available for people who were not afraid. Out of the 32 apprentices, there were about 20 cases of that kind-they could not study in secondary school because they were punished somehow by the communists. Sometimes I went to school to learn how to work and do labor, but the other days I went to work. In some manner I had less time to get my education, but I managed to finish going to the University. D: Oh ok that’s amazing. S: If I was one year younger, they would have accepted me to the secondary school because they did competitions. One year later, they issued a command that people who got first or second place in the competition must be excepted to study. The regime found that it had been a problem that these kids didn’t go to school. I have a strange story about the access to education. There had been people who were actively opposing the regime. Some of their children wanted to attend the university. And at the Czech Technical University, after the revolution, they released all of our files. And we found out that some people were expelled from the University for some reason. And some were not accepted. At that level, because the secret police on the entrance examination day, came to the University, this person was able to find the unwanted student, falsify his test, and interchange his test. And for three years this person was blocked from entering the university by this trick of the secret police. So if you were going to invent something, you could not invent it. D: Leading up to the Velvet Revolution, did you expect the fall of communism? S: I could not imagine that communism would fall down. I never wanted to enter the communist party because I didn’t like it, but I couldn’t imagine it ending. I was prepared for life that I wouldn’t be able to work anywhere in management and that it would be hard to study. At the end of my studies, someone in the University said that there would be a place for me at the University if I caved to the communist party, and the next day the place disappeared. You could chose, you could make it a career in the communist party, or you could survive. D: What were you doing the evening of the first protests of the Velvet Revolution? S: The first evening started with a student manifestation which was allowed ---When I arrived, it was really something which I had not been reading such stuff the whole life before. Somehow people had banners which was evident it was against the regime. One of the speakers was speaking so openly against the regime, that it was something which I couldn’t imagine. Then the students managed to get to the Wenceslas Square. At that time, I had to leave. I left and went to a different square-I did not know that people had been blocked and for some time many of them had been beaten. It was close to Wenceslas Square. After I went to the underground metro, I could not find anything, and so after a half-an-hour I went home. Then I listened to messages. The fact that there was no internet in the Czech Republic, although the internet was young. We listened to a broadcast from America. The broadcast from the Czech Republic was jammed so it was easier to receive the broadcast from America. D: Well it’s good you weren’t there when they started to beat up the people in the crowd. How did things change after the revolution? Did it happen suddenly? S: Well after two weeks, things changed drastically. We could say anything we wanted. The worst and first thing (during communism) was that family members would be punished. That was quite an effective means of resisting it and speaking openly. Well I was a scout leader. Well, scouts were forbidden at that time, so we were somehow surviving. There were some children who were actively protesting the regime. These are children. 8 years old. They were so dangerous, that when they went home from the meeting of the scouts they had two secret policemen walking with them. So you can imagine many people would be really afraid and not accept them to anything. My 5th scout group did accept people, knowing that sometimes our club room had some visitors. You know, it was that way. I understand that many people have been afraid just to talk with people under such communist supervision. D: ok. Continuing the discussion about the Velvet Revolution and the return to democracy, who was Vaclav Havel to you? S: Vaclav Havel was an excellent, outstanding person, a humanist, he was imprisoned several times by the communist government. And I think he did a big job in the beginning of Czechoslovakia and Czech Republic. D: Do you remember anyone you personally knew who stood up to communism? S: At first I knew the parents of those young guys in my scout group who were signing those anti-communist documents who were talking to radio America or Radio Free Europe. So I did know several such people. D: Today, 50 years after the Prague Spring invasion and close to 30 years after the fall of communism, what is life like, and do you still see the effects of communism in Czech people? S: Although you get freedom, you can’t wash everything down of you. There are still some things that originated during communism. Some people thinking that after all there were some people who had better times under communism than later. Yes, it is a long process, which is difficult to speed up. Although now we are close to a democracy, we still have some problems here. Second thing is that Czech Republic was one of the first (technologically advanced) countries before Soviet Union freed us from Hitler. For being a country who was extremely technologically advanced, we had not much advancement during communism so we fell down in the competition. The other thing is we also did not really have any money after the fall of communism. So this is a result which is not devastating but it’s here. D: In your work, have you ever encountered ex-communists? S: Yes, it wasn’t true before 1968, but after there was a big resistive place. After the 1968 some of the communist party decided that they would hire professors who didn’t even have to defend their dissertation. They have changed the numbers this way. Some had to leave because students didn’t like them. Some of them remain there. Some of them are still pretty important. We are currently fighting with some of them. D: Wow, that’s crazy. That’s all the questions I have today. Thank you so much for taking my call. S: Thank you. This is something that happens only once or twice in your life. It’s quite interesting to have lived during that time.

0 Comments

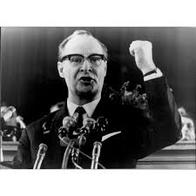

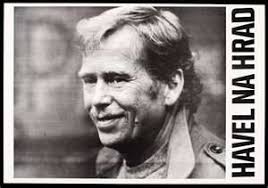

In January of 1968, Alexander Dubček was selected as the first secretary of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (KSC). At this time, Brezhnev, the leader of the USSR, trusted Dubček and allowed him to maintain power in Czechoslovakia. Brezhnev did not anticipate Dubček ’s democratic-leaning reforms. Soon following his assumption to power, Dubček attempted to decentralize the government and grant more rights and freedoms to the people. He coined this “socialism with a human face,” giving the cogs in the machine some liberty once again. Censorship stopped. Restrictions on media, speech, and travel were partially lifted, and the people experienced a brief breath of fresh air from the twenty some years of harsh oppression. Czechoslovakian films were some of the important, creative products of the Prague Spring, in which directors radically affected film styles around the world with their use of absurdity, humor, and critique of communism. Additionally, the Czech radio took advantage of the increase in freedom, and broadcasted anti-communist sentiments. This eventually made it a big target in the Prague Spring invasion. The USSR was not pleased with the growing freedom in Czechoslovakia. As Czechoslovakia was known as the connection between the East and the West, its leaning towards the West with growing freedoms and rights threatened communism in Europe. Brezhnev met with Dubček to try to stop the democratization of the country, and called him multiple times after, when Dubček hadn’t changed his policies. As a response to Dubček’s strong stance against censorship, some 650,000 men from Warsaw Pact troops, including soldiers from the Soviet Union, Bulgaria, Poland, and Hungary, invaded Czechoslovakia. They were coming to save Czechoslovakia from the evil West, from freedom. The invaders killed over 130 people in the immediate attack, leaving over 260 people seriously injured, and some 140 slightly injured. When the Warsaw troops entered Czechoslovakia on August 20th, they first had some trouble reaching Prague. Citizens in outside towns realized what was happening and went out to the streets to either fight or confuse the soldiers. Some painted over street signs, while others met the troops outside to fight. In Liberec, a small town to the north of Prague, citizens threw tomatoes and anything at hand at the tanks rolling in. Nine were killed here, some 45 seriously injured. The troops finally made it to Prague early morning on August 21. Here too, citizens met the tanks out in the streets. They tried to stop the tanks with makeshift barricades, even using their own bodies to form barriers on the roads. Some flipped military vehicles. The most violence happened in front of the radio building. Citizens tried to defend the building, and fought the troops back. Here, 17 were killed, but eventually a tank destroyed the radio building. Once the radio was down, it was easier to control the rest of Prague. Alexander Dubček and other politicians of importance were arrested, and sent back to Moscow for interrogations. They were forced to sign the “Brezhnev Doctrine,” and bring heavy censorship back to Czechoslovakia. The Warsaw troops were coming to help their brothers against the counter-revolution. Soldiers in the invading camps had been told that they were helping their brothers in Czechoslovakia against the dangerous revolutionaries-that they were there to rescue their friends. Tanks and censorship was their offering in friendship. After the invasion, the USSR set up the government in Prague, bringing back censorship in a period of what they called ‘normalization.’ At the onset of their new government, around 70,000 people fled the country, while more than 300,000 people left in later years. They were fleeing a killing machine. Perhaps the numbers of the invasion-less than 200 deaths, seems low for an invasion thus remembered. But, the invasion represents a much higher number of deaths. The re-implementation of Communism meant the snuffing out of freedom. It meant that people were no longer able to be people again; to have a conscience, think what they want, say what they think. It also meant physical death. According to Victims of Communism, the overall death toll of communism worldwide spans from 42,870,000 to 161,990,000. In Eastern Europe alone, communism is responsible for over 1,000,000 deaths. After Dubček was removed from office, Gustav Husák took his place as first secretary. He led the process of ‘normalization,’ restoring censorship, purging the political system of anti-communist sentiment, and strengthening the country’s ties with other socialist nations. Of the 115 members of the KSC Central Committee, Husák replaced 54. Throughout the nation, top levels of leadership were purged. According to the US Country Studies on the Czech Republic, professors, scientists, and social leaders who did not show full support of normalization lost their jobs and were forced to do menial work. Soviet control permeated Czechoslovakian government. In 1970, Czechoslovakia and the USSR signed the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation, and Mutual Assistance, in which Czechoslovakia lost sovereignty and allowed USSR to remain stationed in Czech lands. Soviet leaders kept a close watch of Czechoslovakian politicians. By January 1971, central authority was restored to its pre-Prague Spring level. Though communism permeated every facet of life, pro-freedom sentiments had not died completely among the people. Living in a thwarted environment forced some to find alternate avenues. Like a tree which twists and bends to find light in a shaded glen, leaders seeking freedom for themselves and their brothers found ways to pervade the communist haze. The most famous and celebrated spokesperson for civil rights and freedom, Vaclav Havel, continually searched for ways to undermine the communist regime. Born in a bourgeois family, Havel received a limited education (the communists didn’t like wealth and his dissident family, and wanted to punish success and opinions in many of their forms). This did not stunt his search for academic excellence and artistic expression. When he was 27, his first play, “Garden Party,” which highly criticized communism, premiered at the Prague Theatre in 1963. When Prague Spring was suppressed, he was forced to stop writing, and work as a manual labourer instead. However, this only added to Havel’s enthusiasm. He, among others, published Charter 77, a document in which listed the many civil rights violations of the communist party. This document, though confiscated in its original form, made its way into being published in the Western world, and broadcasted illegally to Czechoslovakians through Radio Free Europe and Voice of America. His efforts to bring down communism led to his imprisonment on multiple occasions. Yet, though he was imprisoned, the communists could not stop his message from spreading. Later, once out of jail, he founded the Civic Forum--a group made up of multiple anti-communist groups. With this, he lead the Velvet Revolution--a 10 day long protest which resulted in the toppling of communism in the Czech Republic. Vaclav Havel reminds us of our humanity--that each and every one of us has a unique conscience. That each is born with reason, and thus must exercise reason in his utmost capacity. That each and every one of us is born equal, and has the right to live, and exercise that equality in freedom of speech, opinion, and thought. He reminds us of who we are at the core, and who each has the capacity to become. Stay tuned to next week's post: an interview with an intellectual who was able to rise to the heights of academia despite being prohibited to study and do manual labor instead. Interesting links: https://www.victimsofcommunism.org/ http://blog.victimsofcommunism.org/victims-by-the-numbers/ http://www.getty.edu/museum/programs/performances/czech_films.html https://www.rferl.org/a/prague-spring-invasion-czech-soviet/29435069.html https://www.radio.cz/en/section/czech-history/the-1968-invasion-when-hope-was-crushed-by-soviet-tanks Prague Spring interviews https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QoIjNjAqH4k https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-XgxLgnpRYw  After I experienced the commemoration of Prague Spring, 1968 in the Czech Republic, my interest in the history of communism in this country peaked. One of my friends from class mentioned that she wanted to go to the Museum of Communism downtown, and I immediately asked to join. What I was about to learn would change my life. I had always known that communist governments were repressive. But, the extent to which they repressed their citizens was unknown to me. I had a fictional picture of communism in my mind: an Animal Farm-like reality in which nobody could trust anybody, wealth was extremely difficult to accumulate, and freedom was nonexistent. But, this fictional idea never was real to me. I imagined the real version of communism to be less harsh--that Czechoslovakia wasn’t repressed that much. I couldn’t have been further from the truth. Communism in Czechoslovakia was extreme. It robbed people of everything they had, including their consciences, personalities, and ability to trust. It made each person just a number in a system, forcing them to act as cogs in the machine rather than human beings. The following is what I learned at the museum: Although it wasn’t until after WWII when the Communist Party officially took control of the country, many citizens sympathized with communism in the early 1920’s. Leading up to the establishment of the Communist Party in the Czechoslovakian government in 1921, Czech lands suffered from droughts and poverty, and thus communism appeared to offer a solution to their problems. By 1928, the party had gained a substantial amount of followers, making it the second-largest party in the Communist International party. After WWII, the USSR dictated the government in Czechoslovakia. Socialist parties were abolished, and the Communist party gained control. Once in control, the Communist Party leaders initiated massive eradications of dissenters. At the start of Communist control in Czechoslovakia, 23,000 people were found guilty of crimes. Of the 23,000, 713 were sentenced to death immediately. In 1945, 75% of industry was in the government’s control, and in 1948, the government put to use the taking of others’ property, or “legalized theft.” Although Klement Gottwald was the president of Czechoslovakia, he had limited control himself. Most of the decisions were dictated to him from the USSR. Thus started what the Museum of Communism calls the “Communist Dictatorship.” From 1948-1968, Czechoslovakia was subject to extreme poverty, doctrination, and oppressive control. The Communists created a new ideal for their citizens: Homo Communism. The new socialist man was the laborer. He volunteered for his community, loved the army, and waved the soviet union flag. To showcase this ideal, the government created many banners and paintings glorifying Homo Communism, including the huge painting attached at the bottom of this article. Because labor was valued so much, and because the Communists in Czechoslovakia thought that the bulk of the community relied on physical labor, the government sponsored many uranium mines. Working in these plants was extremely unhealthy, and the stress of gathering uranium left huge environmental issues in the country, as well as economic. To compensate for the government’s overinvesting in industry, it decided to change the value of its currency overnight and lower its debts. Although a few days before doing so government leaders promised that the money value would not change, they changed the value regardless on June 1, 1953. Imagine going to bed with $50,000 dollars in your bank account, to wake up to only $1,000. The reform made paupers out of the citizens, while it decreased the debt of an extremely inefficient government system. Cash lost about 80% of its value. The West referred to this reform as the “great swindle,” which it surely was. 130 anti-communist strikes occurred as a result of the reform, to which the government acted violently to repress. Additionally to the Homo Communism ideal, and all of the problems it brought with it, communism hacked away at Czech culture. Baby Jesus, who traditionally brings presents on Christmas Eve, was replaced by Grandfather Frost. The Scout program--an important extracurricular program for many Czechs--was replaced with the Pionyr program. The Communists tried desperately to thwart religious practices. Many faithful Catholics could not hold jobs where they had the possibility of affecting the culture. Among many Catholics thus persecuted, Dr. Radomir Maly, a former historian for a museum in the town of Kromeriz, was forced to quit his job and work as a menial worker because he would have had too strong of a religious effect on those around him. Dr. Maly’s story of persecution is a common one for faithful Christians in Czechoslovakia; from 1948 to 1968, the number of priests in the country decreased in half. Many practicing Christians were forced to either stop practicing their religion, or turn to illegal, underground meetings. The persecution of Christians has a lasting effect in Czech Republic. In 1921, about 82% of Czechs identified as Roman Catholic, but by 2011 only 10% of Czechs identified as Roman Catholic. The Communist policies were bad. Taking away freedom anywhere is a violation of human rights. But the ways in which they were enforced are close to unimaginable. The StB was the Czechoslovakian secret police who monitored their neighbors all while remaining under cover of ordinary citizens. StB infiltrated all parts of life. In every avenue of work, members of the StB monitored their neighbors and coworkers. StB kept records of the people they watched. They listened in on phone conversations at switchboards, bugged rooms, and set up secret cameras. If these records hadn’t been burnt, they would have covered several soccer fields, piled a few meters high. In the 1950’s, 422 labor camps were created, in which lived 11,026 residents. Dissidents and non-dissidents alike of the ‘Communist Dictatorship’ were systematically placed in these camps. The Ministry of Justice predetermined how many people they wanted to imprison. Thus, many of the imprisoned had not been loud dissidents of communism, and some hadn’t even committed any crimes. The StB had two rules regarding the placement of people into the prison camps: 1. The people arrested were the only witnesses to their crimes, and 2. The StB could never free someone they arrested. Breaking any of these rules would undermine the StB authority. The StB had several ways of forcing confessions out of their imprisoned: they would torture the arrested by not allowing them to sleep well, waking them every 15 minutes from their cells, they would beat them up physically, inject drugs into their systems, and not let them live until they forced a confession. Travel was hardly an option for Czechoslovakians. Either they travelled to the West illegally (and never returned), or they travelled to the USSR on highly supervised trips. When Czechoslovakians visited the USSR, KGB was vigilant in never letting its visitors see the true face of communism. Escape from Czechoslovakia into Western countries was nearly impossible. Huge barriers and barbed wire fences were built along the borders, and sand plains led up to the barriers to highlight the dark bodies trying to escape against the white sand. Many were killed while trying to escape. Communism was indoctrinated in schools. Children were taught to tell on their parents if their parents ever talked poorly of communism. My grandmother, who grew up in communist Prague, said that she had to be very careful with what she told her children. She admits though, that her children were smart and knew not to say anything, and that most of the other children understood not to talk about communism, too. Additionally, children were taught that wealth was evil. If someone acquired wealth, they were against the common man. The subject of their education was likewise made up of propaganda. For example, children had to write essays on the benefits of their liberators, the Soviet Union. Undoubtedly, if they questioned the essay prompt, or the USSR, they were met with grave repercussions. Thus, Czechoslovakians lived very tough lives. Their commemoration of Prague Spring, 1968 weighs much more when seen with the knowledge of what Czechoslovakians were trying to escape. The goal of the commemorative movement--that the nightmares never go grey--was met with me. The commemoration made me interested in Czechoslovakian history, and made me question my previous knowledge. Now that I know this “Communist Dictatorship” started with the approval of the people, I will be much more skeptical about politicians in my own country, and vigilant that none try to take away my freedom. I hope that learning about communism in Czechoslovakia has the same effect on you, too. Stay tuned for the second part: Prague Spring 1968-Post Communism Read more here: -https://www.catholicworldreport.com/2017/05/19/catholics-in-communist-czechoslovakia-a-story-of-persecution-and-perseverance/ -http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/country_profiles/1844842.stm  This past August 21, the world, especially Czech Republic, commemorated the 50th anniversary of the Prague Spring invasion. Various speakers spoke against the evils of communism, and how the Prague Spring invasion from the USSR and other Warsaw Pact troops threw the nation back into darkness. Luckily for me, I was in Prague in August, receiving my TEFL certificate, and was able to witness many of the commemorations of this pivotal point in Czech history. In 1968, Czechoslovakia experienced a brief period of liberation and artistic creation, called Prague Spring. Coined by then president Alexander Dubcek as “socialism with a human face,” Czech society loosened from a previously oppressive and completely socialized society. Czechoslovakia experienced a burst in creation, giving this time period its name, “Zlata sedesata” (the golden sixties). But, upset with the direction Czechoslovakia was headed in, and wary the country--as seen by many as the connection between East and West Europe--would inspire other countries to adopt looser communist governments, troops from the USSR, ordered by stalinist president Antonin Novotny, along with other Warsaw Pact countries, rolled through Czechoslovakia and re-instated strict communism. All in all, around 250,000 troops invaded Czechoslovakia, including some 6,300 tanks and 250 airplanes. Around 72 Czechs and Slovaks were killed during the invasion, and some 270 injured. Although the numbers may seem low for something commemorated as such, the invasion symbolizes the loss of freedom and the catalyst of many more deaths during the 'normalization' back into the Communist way of life. During the week leading up to the Tuesday, many of the historic locations in Prague housed special events to honor the lives lost in the reoccupation of Czechoslovakia. In Wenceslas Square, where citizens--typically students--historically protested, and where Warsaw tanks famously fired at the Radio station during the reoccupation, several organizations, including Vojenský Historický Ústav Praha and others, sponsored the showing of documentaries on a blow-up screen, posters displaying images of the brutal invasion, speakers, and singers. The goal of the commemoration was twofold: to remember the victims of Communism, and to make sure that Communism and similar ideologies never return. Their logo reflects their goal: “Aby sny nezešedly” (Let not the dreams (read "nightmares") go grey). On Tuesday, August 21, many important locations had commemorations. A concert, organized by Czech Radio, was held in Wenceslas square, where many songs about the invasion were sung. A special video and maps were projected onto the National Museum nearby. Various museums had special exhibits on the invasion, free to the public on Tuesday. In addition, in Kampa, a grassy, tranquil area by the Vltava river, several speakers recounted the events of the haunting day. About 300 melancholic people, holding Czech flags and banners, surrounded a small stage which held three speakers. Among them, a USSR expatriate Mr. Gorbanevska spoke against the ignorance of Communism. Gorbanevska’s family has a detailed history with Communism. The repression of Prague Spring happened when he was young, and living in Russia at the time. His mother Natalya Gorbanevskaya, a strong proponent of freedom, and vocalist against the USSR, was one of the eight people who protested on the Red Square in Moscow several days after the Prague Spring invasion. She brought young Gorbanevska with her, as well as her two other children. All eight protestors were swept up by the KGB within seven minutes of sitting in the square with a Czechoslovakian flag and a banner which read things such as: “мы теряем лучших друзей” (We are losing our best friends), “Ať žije svobodné a nezávislé Československo“ (Long live free and independent Czechoslovakia), and “Позор оккупантам!” (Shame to the occupiers). Most of the seven were subject to harsh treatment, including Gorbanevska’s mother, who was later sent to a psychiatric hospital for being a dissident, diagnosed with “sluggish schizophrenia.” She has been celebrated as a hero in the West, and is well-known for her numerous acts of courage and literary works on the necessity of freedom. At the talk, Gorbanevska humbly opened his speech in a highly accented Czech, saying “Odpust mi, nemluvim Cesky” (Forgive me, I don’t speak Czech). A translator stood by his side and translated his Russian into Czech for the younger people in the crowd. For a people who had to learn Russian under the occupation, hearing Russian would be a hard thing on such a day. Gorbanevsky’s opener, however, created a platform on which he and the Czechs listening could together mourn the invasion. He continued to say, “I wanted to share a few words. A normal person to normal people.” Gorbanevsky’s message was brief and direct: we must never forget the atrocities of Communism, and must actively reject it in all of its future forms. He dwells on current Russians’ ignorance of the repression, and how refusing to learn about the evils of the USSR based on the fact that these events took place in the past is an unforgivable excuse. If we forget the history of Communism--how it first started out as a political party which gained much popularity but evolved into a soul-killing machine--we risk repeating it. In his talk, he chastises the Czech president, Miloš Zeman, for his weak stance against the Communist party in the Czech Republic. To the mention of Zeman, a rustling went through the crowd, stirring everyone a brief period of whistling in disapproval of Zeman. They’d been stabbed in the back by the secret police, their own brothers, countless times during Communist occupation. Betrayal by their president is close to unbearable. Gorbanevsky concluded his speech by encouraging the crowd to never forget the tanks rolling into Prague, and to never tolerate limitations of freedom. He encouraged everyone in the crowd to continue protesting injustice everywhere, even if they risk persecution. Protesting evil is the right thing to do. Following Gorbanevsky’s speech, the founder of the “The Memory of a Nation” project, a non-profit organization, talked about his work in sharing stories of normal people’s lives under Communism. His work has the same goal as those who organized commemorations throughout Prague--that people should never forget Communism, and never stop fighting for freedom. After all of the speakers held the stage, a young singer was called to the stage. She sang the Czech national anthem, “Kde domov muy” (Where my home is), and the whole crowd joined. Following the song, members of the crowd lit candles for people they knew who died at the hands of the Communists during the occupation (the intellectuals, celebrities, and politicians who wouldn’t promote the USSR, as well as many others). They processed from Kampa to the statues memorializing the enemies of the state, and lay the candles at the feet of the statues. At the statue’s side, a scout (Scouts had been outlawed under Communism) held up the Czech flag. People reverently placed their candles down by the statues, and quietly related their stories to their neighbors. This experience taught me many things. It explained the quiet stillness in the crowded metros, and the hard, emotionless face of the passersby. Communism may be gone in the Czech Republic, but its effects still linger. We must never forget what Communism was, and how it came to be here, but we also must be willing to move on and trust others again, rejoice, and enjoy this life. Stay tuned for my impression and recap of the Museum of Communism next. Interesting links for follow-up research: -http://www.vzpominka1968.cz/cz/s1193/c2863-Rocnik-2018 -http://www.pametnaroda.cz/ -https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e12rGRO4JuA |

Jessica De GreeJessica teaches 5th grade English and History as well as 11th grade Spanish III at a Great Hearts Academy in Glendale, AZ. In addition to teaching, she coaches JV girls basketball and is a writing tutor for The Classical Historian Online Academy. Jessica recently played basketball professionally in Tarragona, Spain, where she taught English ESL and tutored Classical Historian writing students. In 2018, she received her Bachelor's degree in English and Spanish from Hillsdale College, MI. Archives

April 2020

Categories

All

|

|

SUPPORT

|

RESOURCES

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed