This past week, I went on a road trip in northern Thailand. We rented a car – an interesting experience, given that Thais drive on the opposite side of the road, and many ignore common sense and the law of the land while behind the wheel – and took off for the nation's most mountainous province, Mae Hong Son. We covered about 360 miles over the course of five days, with a good mixture of scenic driving, sightseeing, eating, and adventuring by bike and on foot. It was my favorite trip within Thailand, at least in terms of the location: quaint and peaceful mountain villages and cities, comfortable but not overly developed, and nearly untouched by tourists. Many of the towns reminded me of farming villages in Europe. Perhaps the most spectacular one, though, looked different altogether. Ban Rak Thai, a village of about 1000 people, sits just a few miles away from the Burmese border. The town looks like a dream – surrounded by tea fields, nestled in the heart of the mountains, it's got a truly ethereal quality. It also looks quite different than many Thai villages, because it is Chinese. The village was founded by members of the 'Lost Division' of the KMT. The KMT, or Kuomintang Nationalist Army, was the loosing force during China's Civil War, which was won by Mao Zedong's Red Army. Many soldiers from the KMT escaped to Taiwan, but some headed west into Myanmar and Thailand. They stayed there for decades, fighting off Burmese troops and staging raids against the Communists in China. However, as the years wore on, the soldiers and their families tried to make a home for themselves. Many started smuggling opium and other drugs through the hills, where government forces had a hard time finding them. Meanwhile, others started fighting Thai Communists. It wasn't until thirty years ago that the soldiers put down their weapons and started growing tea at the request of the government. Today, the KMT villages – there are 64 of them – are the image of peace. Ban Rak Thai even has resorts that bring Thais and Chinese in to drink tea and eat Chinese food. We thoroughly enjoyed our short stay in town.

1 Comment

Today (November 25) is one of the most important festivals in Thailand: Loy Krathong, or the lantern festival. Tonight, millions of people throughout Thailand will let small lantern boats sail into the river. It's one of the most beautiful festivals in the country, known for its joyful atmosphere and focus on relationships. Many families celebrate Loy Krathong together, while couples are supposed to let their boats sail together – if the boats stay close, it means a good year for love, but if they separate, bad luck lies ahead. Historically, Loy Krathong dates back beyond the memory of any living Thai peoples. The festival was originally dedicated to the Hindu gods Shiva, Vishnu, and Brahma. Since Thais are Buddhists, the festival was changed in meaning to stay attractive to the local people, much like the Roman celebration of the coming of the sun was changed to Christmas. According to legend, the first Loy Krathong, which just means "lantern boat," set sail nearly 800 years ago during the Sukhothai period, which is the beginning of Thai history. Today, many Thai people believe that the purpose of Loy Krathong is to worship the footprint of the Buddha at the Nammathanati River in India, one of the most revered places for Buddhists. Even though the Buddha was just a man, and told his followers to treat him like a man, many people act as if he were a god. For these people, Loy Krathong has religious importance. However, even for people who aren't religious, Loy Krathong is a powerful festival, one that brings the whole country together. I'll be volunteering at a local temple to sell lantern boats, and I'm very interested in seeing what happens. It's crazy to think that I'm entering the final stretch of my time in Thailand. After several months of adventure and exploration, there are only 4 and a half weeks left of school. There's one big journey between me and finals: a trip to Myanmar, formerly known as Burma. I'm very excited for this journey, and history should be a big part of the experience.

Myanmar's two names speak to the nation's diverse heritage: over 100 different peoples live in the country. The largest group, the Bamar, gives the country one of its names. Myanmar has been populated for thousands of years, and a number of empires called the region home. The Burmese were once a dangerous force in Southeast Asia, and they destroyed one of Thailand's great kingdoms, Ayutthaya, several hundred years ago. In 1824, the British conquered and colonized the region. For the next 120 years, they ruled over Myanmar, despite the sometimes violent protests of local people. In 1948, after the horrors of World War II, Burma gained its independence. However, less than fifteen years later, the Burmese military staged a coup. For the next fifty years, democracy was virtually dead in Burma: generals ruled over all aspects of the society, and the country became one of the poorest in the world. In 1990, after years of protest and thousands of civilian deaths, the country held its first election. The National League for Democracy, lead by Nobel-Prize winning Aung San Suu Kyi, won 80% of the seats in Parliament. However, the military refused to turn power over, and ruled until 2011. In the last five years, the government has changed slightly, opening up space for more democratic processes. Yet, the generals have also developed a plan for 'disciplined democracy,' one that guarantees the military 25% of the seats in parliament, no matter what happens. This week, the country held elections and, once again, Aung San Suu Kyi's government won a large majority of seats. Time will tell how these events affect Myanmar's society. In the meantime, foreigners have been allowed to visit the country for the first time ever. I'm interested in seeing what this almost untouched land is like.  I just returned from an amazing adventure: a week spent in Japan. My journey took me to the capital, Tokyo, where I spent three days visiting temples, parks, and interesting parts of the city. Japan is a very modern nation, with highly planned and regimented cities that offer a sense of peace and order not found in Western metropolises. In addition to Tokyo, I traveled to Kyoto, the nation's ancient capital, and explored the region, camping by a small town near a great lake. On the final day, I woke up with the sun and hitch hiked back to Tokyo. The Japanese people I met along the way were extremely friendly and accommodating, and I think that I could spend some years living there. While Japan's present is interesting, the country's history is almost incredible. While the islands that make up Japan have been settled for tens of thousands of years, they have remained relatively isolated for much of this time. For example, during the reign of the Tokugawa shogunate, a rule that lasted for over 260 years, foreigners were only allowed to trade with Japan in one port, and very few received imperial support. However, that all changed in 1853, when an American commodore named Matthew Perry sailed to Japan with heavily armed ships. He ignored the emperor's requests and demanded that Japan open up a trading relationship with America. This event was met with alarm throughout Japan. Many Japanese people at the time believed that the emperor was a god, so it was almost unbelievable that a man like Perry might ignore the emperor. Within the span of fifty years, Japan became a highly advanced modern nation, one that had a complex system of railroads and telegraphs, highly respected medical and scientific institutions, and a powerful navy. Along with this quick rise to power, the Japanese developed a highly imperialistic form of nationalism, one that lead to aggression and war. During World War II, the Japanese sided with the Axis powers, and fought viciously until the atomic bomb destroyed Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Then, after the war, America restructured Japan again, this time finding a way to instill values of peace and productivity in the nation. Now, many of the world's cars and electronics come from Japanese companies. This roller-coaster ride would have been impossible for anyone to imagine just 150 years ago. Over the past 8 weeks, I've been contributing to an organization that aids refugees as an intern. I've learned a lot on the job, which also includes a writing position. I've been researching and writing about different human rights issues in South East Asia. Most recently, my focus as been on land grabbing, which is when large companies, some of them government-owned, take land away from local people to start planting crops that they can sell to people all over the world, like rubber, which people use for tires. It's interesting to see how the things that people in the West buy affect the poor all over the world.

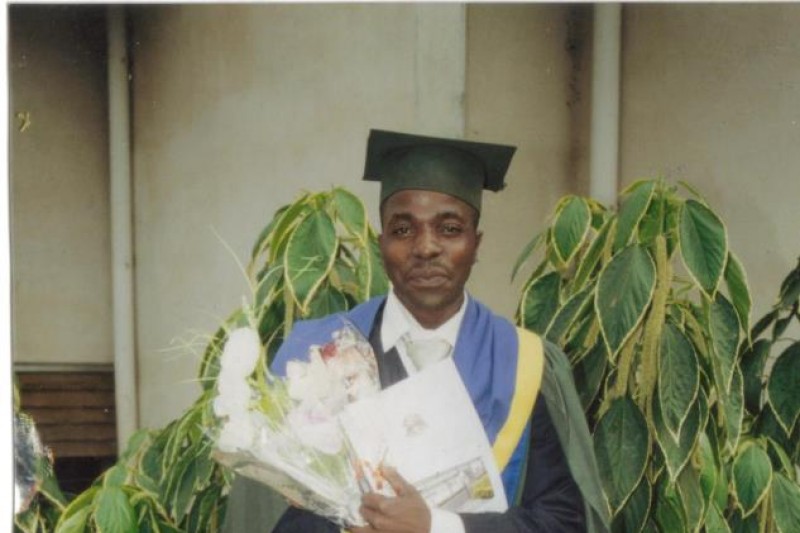

Another interesting issue that I've encountered has been the struggle for independence in Southern Cameroon. Cameroon has a complex colonial history; it was, at different points, controlled by British, French, and German powers. Thus, different parts of the country speak different languages, and at the end of colonialism, no one was entirely sure how Cameroon would be organized. The process of independence began in the 1950s, and in 1959, Southern Cameroons effected the first democratic transfer of power in 20th century Africa. Eventually, the UN gave the people who live in Cameroon several options, including unification with Nigeria or joining the French and English speaking parts of the country together into Cameroon. When the country was formed, the government of Cameroon was a federal government, composed of two states – one, the French-speaking 'La Republique du Cameroun,' and the other, 'Southern Cameroons.' For the first several years, these two states coexisted on equal terms, and, while they still experienced problems, they had a functioning democracy. However, in 1972, the leader of La Republique du Cameroun announced a 'unitary government,' in which South Cameroons could not keep its own legal traditions. Since then, people in South Cameroons have reported many abuses on the part of government officials, and they have few opportunities to change their nation, as many political parties are outlawed. Members of the Southern Cameroons National Council are regularly arrested for holding meetings, and some have been tortured and killed. Today, Southern Cameroon holds a place on the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organisation. I've been visiting a political refugee from Cameroon for some time now – he went through some horrible things in his home country when he spoke out against oppression. Meeting with him has been fascinating and inspiring, and also sad – I still know very little about Cameroon, and there must be many other places like it in the world.  Peter is a 28-year old political refugee from Cameroon. I met him while visiting Bangkok's Immigration Detention Center (read: prison), where asylum seekers, even those recognized by the United Nations, are detained for years at a time in inhumane conditions. In the IDC , inmates are literally stacked on top of each other in cells meant for 15 people (many house more than 100). They receive inadequate food, are forced to drink Thailand's tap water, and often suffer from debilitating diseases. Peter fled Cameroon, where he experienced oppression and torture as a result of his human rights activism (read here and here to learn more), in hopes of finding safety. Yet, thanks to Thailand's legal system, he's been stuck in IDC for over 8 months, and his health is suffering. He has already been hospitalized and lives in fear of contracting a major illness. The thin rice gruel that comprises breakfast, lunch, and dinner in the IDC leaves his immune system with little energy. Each time I speak with Peter, he talks of his hope, his faith, and the necessity of positivity. Like many of the inmates, Peter finds strength in the Bible, and others call him "the pastor," as he organizes Bible readings, prayer groups, and meditations for those inside. Getting to know him has been an eye-opening experience. Recently, Thailand's immigration department has allowed refugees to post a bail of 50,000 Thai Baht, which comes in at just under $1,400 USD. After posting bail, they are allowed to live and move freely within Thailand as they await relocation to a third country. Peter is confident that his health will improve once he is out of the detention center. Any amount that you can spare will bring him closer to freedom. Go here to learn more about donating. Questions? Email Adam at Adam's Email. One of the most interesting parts of studying abroad in a developing country is the discovery of different concepts of rights. Living in Thailand can be difficult at times simply because of the way that the government works; people here do not have many freedoms that I take for granted, such as speech, as their education system keeps them from criticizing their rulers. Right now, Thailand is under a military dictatorship, which means that generals are in charge of all of the decisions for the entire country. Ever since the military took over in 2014, there have been many human rights issues in this country, issues that affect everyone from students to refugees. Sadly enough, this isn't the first time that Thailand's government has failed to secure the rights of all people within its borders.

I study at Thammasat University, which has a proud tradition of political activism that stretches back to its founding in the 1930s. For many years, Thammasat was the place where demonstrations began, where people gathered to discuss the problems with their country, and where change happened. In 1973, students from many universities banded together at Thammasat to protest the rule of a military government that had held power for decades. The protests soon gained the approval of the public, and soon they included 500,000 people. Over the course of several days, the military killed about 100 students, but in the end, the military government resigned: Thailand was a democracy once again. However, just 3 years later, tensions from nearby Vietnam, which had just fallen to Communism, reached Bangkok. Members of the military wanted to take the power back, and started to call reformers 'Communists' in an effort to gain international support. Since students tend to be liberal, and in Thailand at the time, this meant being critical of the wealthy royal and military elite, they were seen as a threat. In October of 1976, police responded to a political cartoon by surrounding Thammasat University. On the morning of October 6, police and military units opened fire on students. Over the next few hours, they killed hundreds of students, hanging many. Others were beaten, tortured, and imprisoned. Meanwhile, the military took power once again – and the West looked away. Over the next few years, America sent Thailand tens of millions of dollars in military and economic aid. Today, many Thai history books don't teach kids about 1976. Over the last ten years, the government has put pressure on Thammasat University, hoping to change the sort of students that attend the school. As a result, it has fallen from its former spot as one of the nation's finest universities, and an increasing amount of students come from wealthy families, uninterested in changing their society. It's a complicated environment, one that changes as quickly as the weather in Bangkok. One of the most interesting things about Thailand is its government. Unlike many Western countries, Thailand has never been a full democracy. There is a long history of authoritarian rule here (authoritarian is when one person, or a group of people, have much more power than everyone else – they author the laws, and enforce them as well), and in the last few years, rising tensions between different groups of people have resulted in violence. Now, a military government has stepped in to stabilize the country, although many are worried that they will stay for much longer than is necessary. Just last week, Thailand's constitutional drafting committee rejected its own draft – the 20th try at a Thai constitution – and it'll be about two years before the next public election.

Here, if you criticize the King and Queen, even past kings and queens, you can get sent to prison for 20 or 30 years. Other restrictions on free speech make press coverage of certain issues dangerous. As a Westerner, I have my own views of these laws. But I've also had some interesting conversations with educated Thais who like it this way. "I prefer an authoritarian form of government," one of my schoolmates told me over dinner a few nights ago. "I think it's important for people to have an example to look up to, and in America, where you have all this freedom, people still just want more and more. So I don't think that's any better." My first thought at hearing this was, "Wow, your education system did a good job." The history that Thai students are taught in school is all about the greatness of Thailand's kings, and it tells students about all the ways in which they protected the nation from its evil neighbors. People learn, from an early age, that without the King and Queen, who they call "Dad and Mom," society would fall apart. My second thought was, "Wow, my education system did a good job." In America, our national history also tells a certain story. In schools, we pledge allegiance to the flag, and many of us are taught to associate America with virtue ("a shining city on a hill"). At the same time, our policies during the Cold War strengthened Thailand's military as the nation further restricted free speech, labeling any criticism of human rights abuses as "Bolshevik propaganda" and throwing people into jail - or worse. So while I believe that people deserve to have a say in the way that they're governed, it's difficult to say that my friend is wrong. She was just learning history. This weekend, I chose to stay in Bangkok, as I had a meeting for an internship I'm pursuing here. I won't talk about it too much now, but it includes visiting refugees from Pakistan, Cameroon, and Vietnam at a detention center, basically a prison, where many live for as much as 2 years without gaining an interview. The day after my meeting, I went to a historical park called Muang Boran, or The Ancient City. It's a massive complex, spanning 240 acres, and inside there are miniatures of monuments from throughout Thailand – in fact, the entire park is a to-scale model of the kingdom.

The monuments, while miniatures of the originals, were still huge, with many towering at least 50 feet high. Some of them housed beautiful artworks, mother-of-pearl thrones, and Buddha statues. A river ran through the entire park, complete with its own floating market. It was a surreal experience, made more so by the slight rain that showered down as my friend and I biked through the city. This experience brought up some interesting thoughts. Muang Boran was founded by a man who wanted to educate Thai people about their heritage. He thought that building a historic park that showcased the wonder of Thailand's monuments would inspire people with respect for their own culture. The park is also open to foreigners, and like many attractions in Thailand, it costs twice as much to go if you're not a local. The park took years to complete; the details on many of the buildings required the work of skilled craftsmen, and the architect, Lek Viriyaphant, visited many of the 116 monuments himself to ensure that the replicas were accurate, while experts from the National Museum helped as well. During my time at the park, I had lots of time to think about the importance of religious art. In Thailand, religious symbols are everywhere. Museums like Muang Boran are often filled with Buddha statues and other sacred objects. My question is, what makes something holy? Is a replica of a religious statue just as sacred as the original? Every Thai person that I've seen at a museum has reacted to the statues around them as if they were the originals: they often get down on their knees, light incense, and maintain silence. On the other hand, these statues are housed in a museum that's open to non-Buddhists, like me, who treat them like artwork. My friend Tessa said that objects like Buddha statues are important because of the intention with which they were built, and that she has more respect for the originals than a replica on display. I think I agree with her, but it's a tricky issue, especially since the locals seem to respect the object itself, regardless of the situation. Last weekend, I journeyed to the Kanchanaburi province with my French friend Leo. As soon as we got to town, we rented motorbikes and took off on a 90-minute ride to the Erawan Waterfall, one of Thailand's most beautiful natural destinations. The falls are seven stories high, and the water is perfectly clear. Fish swim around under giant trees where monkeys play, rockslides abound, and the whole scene is one of peace – except that the lower four levels are filled with tourists and a snack bar waits at the bottom. In addition to Erawan, we rode through rural areas, visiting caves, temples, and a great historic city built by the Khmer Empire in the 12th century.

Towards the end of our journey, we stopped along the famous Death Railway. This railroad runs from Thailand to Burma, or Myanmar, and it earned its name during World War II. Thailand fought on the side of the Japanese, who had grand plans to dominate Asia. The Japanese forced 200,000 Asian civilians and 60,000 POWs, or prisoners of war, to complete the railroad in just a year and a half, despite engineers' predications that it would take four or five to construct. The railway was built so quickly because the Japanese forced workers to build in horrible conditions. We now think that about 100,000 Asian civilians and 16,000 prisoners of war died during the construction of the railway. POWs were forced to live in bamboo huts, where they had little to no food and often suffered from terrible diseases. Cruel punishments were normal for those who refused to work, and many awful stories survive from those days. Leo and I visited a small museum commemorating the railroad. The museum was interesting, but it only spoke of the prisoners of war, not the civilians. We also visited the memorial cemetery, located right in the center of Kanchanaburi. Each gravestone was inscribed with the dates of the soldiers' birth and death, their name, and an epitaph (some words to dedicate the burial). Some were as young as 20 or 21, and many epitaphs read "we're proud of you, son." It was a heavy experience. There are some strange things about the modern-day memorial sites. If you want to walk on the actual railway, you can – and you'll be surrounded by dozens of people. The path to the railway is lined with 20 or 30 vendors, selling all sorts of souvenirs, ice cream treats, and even clothing. In the museum, there is no mention of Thailand's actions during the war – we even heard a tour guide explaining that Thailand was forced to fight on the side of Japan, which simply isn't true. And, there is almost no mention of the deaths of the forced civilian laborers, even though 100,000 of them passed away building the railway. Many visitors come to the area just because a Hollywood movie, "The Bridge Over the River Kwai," is loosely based on the region's history during the War. So, this weekend gave me lots to think about. Erawan Waterfall |

Adam De GreeI am a senior in college, studying philosophy, and am visiting family in the Czech Republic and travelling and studying in Europe and Asia. Archives

January 2016

Categories

All

|

|

SUPPORT

|

RESOURCES

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed