This past week, I went on a road trip in northern Thailand. We rented a car – an interesting experience, given that Thais drive on the opposite side of the road, and many ignore common sense and the law of the land while behind the wheel – and took off for the nation's most mountainous province, Mae Hong Son. We covered about 360 miles over the course of five days, with a good mixture of scenic driving, sightseeing, eating, and adventuring by bike and on foot. It was my favorite trip within Thailand, at least in terms of the location: quaint and peaceful mountain villages and cities, comfortable but not overly developed, and nearly untouched by tourists. Many of the towns reminded me of farming villages in Europe. Perhaps the most spectacular one, though, looked different altogether. Ban Rak Thai, a village of about 1000 people, sits just a few miles away from the Burmese border. The town looks like a dream – surrounded by tea fields, nestled in the heart of the mountains, it's got a truly ethereal quality. It also looks quite different than many Thai villages, because it is Chinese. The village was founded by members of the 'Lost Division' of the KMT. The KMT, or Kuomintang Nationalist Army, was the loosing force during China's Civil War, which was won by Mao Zedong's Red Army. Many soldiers from the KMT escaped to Taiwan, but some headed west into Myanmar and Thailand. They stayed there for decades, fighting off Burmese troops and staging raids against the Communists in China. However, as the years wore on, the soldiers and their families tried to make a home for themselves. Many started smuggling opium and other drugs through the hills, where government forces had a hard time finding them. Meanwhile, others started fighting Thai Communists. It wasn't until thirty years ago that the soldiers put down their weapons and started growing tea at the request of the government. Today, the KMT villages – there are 64 of them – are the image of peace. Ban Rak Thai even has resorts that bring Thais and Chinese in to drink tea and eat Chinese food. We thoroughly enjoyed our short stay in town.

1 Comment

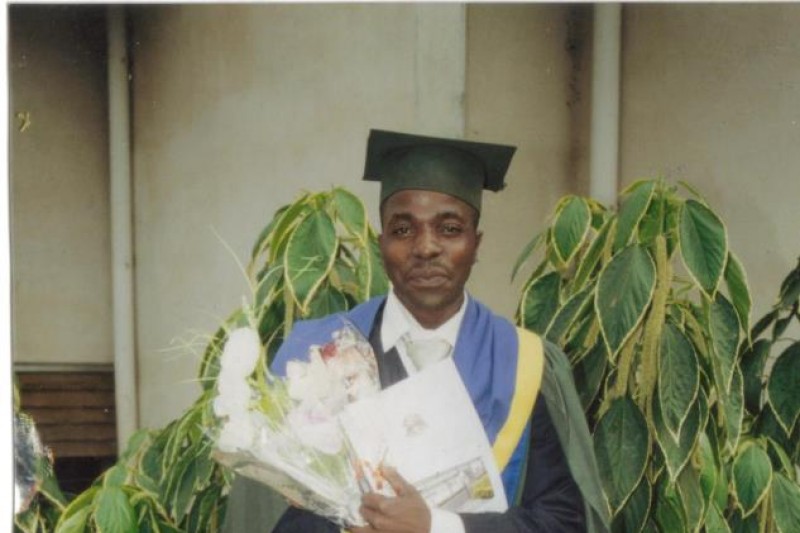

Today (November 25) is one of the most important festivals in Thailand: Loy Krathong, or the lantern festival. Tonight, millions of people throughout Thailand will let small lantern boats sail into the river. It's one of the most beautiful festivals in the country, known for its joyful atmosphere and focus on relationships. Many families celebrate Loy Krathong together, while couples are supposed to let their boats sail together – if the boats stay close, it means a good year for love, but if they separate, bad luck lies ahead. Historically, Loy Krathong dates back beyond the memory of any living Thai peoples. The festival was originally dedicated to the Hindu gods Shiva, Vishnu, and Brahma. Since Thais are Buddhists, the festival was changed in meaning to stay attractive to the local people, much like the Roman celebration of the coming of the sun was changed to Christmas. According to legend, the first Loy Krathong, which just means "lantern boat," set sail nearly 800 years ago during the Sukhothai period, which is the beginning of Thai history. Today, many Thai people believe that the purpose of Loy Krathong is to worship the footprint of the Buddha at the Nammathanati River in India, one of the most revered places for Buddhists. Even though the Buddha was just a man, and told his followers to treat him like a man, many people act as if he were a god. For these people, Loy Krathong has religious importance. However, even for people who aren't religious, Loy Krathong is a powerful festival, one that brings the whole country together. I'll be volunteering at a local temple to sell lantern boats, and I'm very interested in seeing what happens.  Peter is a 28-year old political refugee from Cameroon. I met him while visiting Bangkok's Immigration Detention Center (read: prison), where asylum seekers, even those recognized by the United Nations, are detained for years at a time in inhumane conditions. In the IDC , inmates are literally stacked on top of each other in cells meant for 15 people (many house more than 100). They receive inadequate food, are forced to drink Thailand's tap water, and often suffer from debilitating diseases. Peter fled Cameroon, where he experienced oppression and torture as a result of his human rights activism (read here and here to learn more), in hopes of finding safety. Yet, thanks to Thailand's legal system, he's been stuck in IDC for over 8 months, and his health is suffering. He has already been hospitalized and lives in fear of contracting a major illness. The thin rice gruel that comprises breakfast, lunch, and dinner in the IDC leaves his immune system with little energy. Each time I speak with Peter, he talks of his hope, his faith, and the necessity of positivity. Like many of the inmates, Peter finds strength in the Bible, and others call him "the pastor," as he organizes Bible readings, prayer groups, and meditations for those inside. Getting to know him has been an eye-opening experience. Recently, Thailand's immigration department has allowed refugees to post a bail of 50,000 Thai Baht, which comes in at just under $1,400 USD. After posting bail, they are allowed to live and move freely within Thailand as they await relocation to a third country. Peter is confident that his health will improve once he is out of the detention center. Any amount that you can spare will bring him closer to freedom. Go here to learn more about donating. Questions? Email Adam at Adam's Email. One of the most interesting parts of studying abroad in a developing country is the discovery of different concepts of rights. Living in Thailand can be difficult at times simply because of the way that the government works; people here do not have many freedoms that I take for granted, such as speech, as their education system keeps them from criticizing their rulers. Right now, Thailand is under a military dictatorship, which means that generals are in charge of all of the decisions for the entire country. Ever since the military took over in 2014, there have been many human rights issues in this country, issues that affect everyone from students to refugees. Sadly enough, this isn't the first time that Thailand's government has failed to secure the rights of all people within its borders.

I study at Thammasat University, which has a proud tradition of political activism that stretches back to its founding in the 1930s. For many years, Thammasat was the place where demonstrations began, where people gathered to discuss the problems with their country, and where change happened. In 1973, students from many universities banded together at Thammasat to protest the rule of a military government that had held power for decades. The protests soon gained the approval of the public, and soon they included 500,000 people. Over the course of several days, the military killed about 100 students, but in the end, the military government resigned: Thailand was a democracy once again. However, just 3 years later, tensions from nearby Vietnam, which had just fallen to Communism, reached Bangkok. Members of the military wanted to take the power back, and started to call reformers 'Communists' in an effort to gain international support. Since students tend to be liberal, and in Thailand at the time, this meant being critical of the wealthy royal and military elite, they were seen as a threat. In October of 1976, police responded to a political cartoon by surrounding Thammasat University. On the morning of October 6, police and military units opened fire on students. Over the next few hours, they killed hundreds of students, hanging many. Others were beaten, tortured, and imprisoned. Meanwhile, the military took power once again – and the West looked away. Over the next few years, America sent Thailand tens of millions of dollars in military and economic aid. Today, many Thai history books don't teach kids about 1976. Over the last ten years, the government has put pressure on Thammasat University, hoping to change the sort of students that attend the school. As a result, it has fallen from its former spot as one of the nation's finest universities, and an increasing amount of students come from wealthy families, uninterested in changing their society. It's a complicated environment, one that changes as quickly as the weather in Bangkok. One of the most interesting things about Thailand is its government. Unlike many Western countries, Thailand has never been a full democracy. There is a long history of authoritarian rule here (authoritarian is when one person, or a group of people, have much more power than everyone else – they author the laws, and enforce them as well), and in the last few years, rising tensions between different groups of people have resulted in violence. Now, a military government has stepped in to stabilize the country, although many are worried that they will stay for much longer than is necessary. Just last week, Thailand's constitutional drafting committee rejected its own draft – the 20th try at a Thai constitution – and it'll be about two years before the next public election.

Here, if you criticize the King and Queen, even past kings and queens, you can get sent to prison for 20 or 30 years. Other restrictions on free speech make press coverage of certain issues dangerous. As a Westerner, I have my own views of these laws. But I've also had some interesting conversations with educated Thais who like it this way. "I prefer an authoritarian form of government," one of my schoolmates told me over dinner a few nights ago. "I think it's important for people to have an example to look up to, and in America, where you have all this freedom, people still just want more and more. So I don't think that's any better." My first thought at hearing this was, "Wow, your education system did a good job." The history that Thai students are taught in school is all about the greatness of Thailand's kings, and it tells students about all the ways in which they protected the nation from its evil neighbors. People learn, from an early age, that without the King and Queen, who they call "Dad and Mom," society would fall apart. My second thought was, "Wow, my education system did a good job." In America, our national history also tells a certain story. In schools, we pledge allegiance to the flag, and many of us are taught to associate America with virtue ("a shining city on a hill"). At the same time, our policies during the Cold War strengthened Thailand's military as the nation further restricted free speech, labeling any criticism of human rights abuses as "Bolshevik propaganda" and throwing people into jail - or worse. So while I believe that people deserve to have a say in the way that they're governed, it's difficult to say that my friend is wrong. She was just learning history. This weekend, I chose to stay in Bangkok, as I had a meeting for an internship I'm pursuing here. I won't talk about it too much now, but it includes visiting refugees from Pakistan, Cameroon, and Vietnam at a detention center, basically a prison, where many live for as much as 2 years without gaining an interview. The day after my meeting, I went to a historical park called Muang Boran, or The Ancient City. It's a massive complex, spanning 240 acres, and inside there are miniatures of monuments from throughout Thailand – in fact, the entire park is a to-scale model of the kingdom.

The monuments, while miniatures of the originals, were still huge, with many towering at least 50 feet high. Some of them housed beautiful artworks, mother-of-pearl thrones, and Buddha statues. A river ran through the entire park, complete with its own floating market. It was a surreal experience, made more so by the slight rain that showered down as my friend and I biked through the city. This experience brought up some interesting thoughts. Muang Boran was founded by a man who wanted to educate Thai people about their heritage. He thought that building a historic park that showcased the wonder of Thailand's monuments would inspire people with respect for their own culture. The park is also open to foreigners, and like many attractions in Thailand, it costs twice as much to go if you're not a local. The park took years to complete; the details on many of the buildings required the work of skilled craftsmen, and the architect, Lek Viriyaphant, visited many of the 116 monuments himself to ensure that the replicas were accurate, while experts from the National Museum helped as well. During my time at the park, I had lots of time to think about the importance of religious art. In Thailand, religious symbols are everywhere. Museums like Muang Boran are often filled with Buddha statues and other sacred objects. My question is, what makes something holy? Is a replica of a religious statue just as sacred as the original? Every Thai person that I've seen at a museum has reacted to the statues around them as if they were the originals: they often get down on their knees, light incense, and maintain silence. On the other hand, these statues are housed in a museum that's open to non-Buddhists, like me, who treat them like artwork. My friend Tessa said that objects like Buddha statues are important because of the intention with which they were built, and that she has more respect for the originals than a replica on display. I think I agree with her, but it's a tricky issue, especially since the locals seem to respect the object itself, regardless of the situation. Living in Bangkok is a wild experience. This city is massive, and the noise of traffic is inescapable. However, unlike some of the big cities I've visited in the West, Bangkok is also approachable on a human level. Maybe it's because of all of the street vendors selling food and clothing. Maybe it's because of the laid-back attitudes of many Thai people. Maybe it's because of all the potted plants. In any case, there is always a chance of running into someone or something interesting and new here.

One day about a month ago, I took off on foot for the Tesco, a supermarket chain that is big in Europe and Asia. I got lost and ended up under a bridge, by a food vendor. I bought dinner and sat down next to some Thais playing a form of checkers. They immediately invited me to play and insisted that I keep playing. After 45 minutes, I pulled out a chess set which I bought in Budapest in the hopes of playing with people throughout my travels. They went wild. We barely spoke to each other, but we quickly became friends. Now, every Thursday, I have about 90 minutes of chess and checkers with some motorcycle taxi drivers under a bridge in Bangkok. Last week, I introduced them to Led Zeppelin and the Doors during a thunderstorm. It's pretty much everything that I could ever want. It's also pretty remarkable that chess and checkers are played on different sides of the world – although the rules are different here. Thai chess is much slower, and many of the pieces can't move more than one tile at a time. As it turns out, though, chess actually came from this side of the world, in nearby India, over 1500 years ago. From India, the game traveled to Persia, and from there, Arabs took it to Europe, where it grew and changed into what we know today. However, as I've discovered, there are many different ways to play chess. http://thailandlandofsmiles.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/11/ThaiChess10.jpg This past weekend, I left Bangkok for the island of Ko Si Chang, which sits about 40 miles away in the Gulf of Thailand. After a five-hour journey, I arrived at the ferry with minutes to spare. Thailand is still a developing country, and its population has more than doubled over the last 30 years. As a result, traffic is very bad. However, once we got to the ferry, all the road noise melted away.

For thousands of years, Thailand has been a center of trade. Because most of the region's inland areas were heavily forested and filled with tigers, snakes, elephants, and bugs of all kinds, people lived by the ocean. Massive port cities developed, and goods from China, India, and even the Mediterranean came and went. Today, many giant ships use the channel between Ko Si Chang and the mainland as a rest stop. There must have been 50 or 60 within view from the shore. As the ferry wove through giant floating islands of steel, I couldn't help but think of Burning Man, an American festival I'm missing out on this year. Ko Si Chang is a small island, and not nearly as busy as many of Thailand's attractions. My friends and I were some of the only white people there, which was nice for a change. We rented motorbikes and spent our days hiking, visiting temples, and eating fresh seafood. Thailand is a Buddhist country, and everywhere you go, you're sure to find beautiful temples and shrines. Buddhism came from India about 2500 years ago. and it is an atheist religion, which means that while Buddhists have their own rituals and beliefs about the world, they do not believe in a god. However, in all other ways, they are very similar to many of the world's great religions. They have monasteries, artworks, and revered texts. They preach about not killing, recognizing the connections between beings, and controlling desire. Buddhism in Thailand is slightly different than other countries. Here, monks can leave monasteries whenever they want to. There is a custom for Thai men to be ordained a monk for 3 months, and live in a monastery, beg for food, and study the Dharma, or Buddhist beliefs. Then, they go back into society. When you get away from the big cities, Thailand is very peaceful. My time on Ko Si Chang was a welcome relief from life in Bangkok. I've arrived in Bangkok for the next stage of my 9-month journey. Bangkok is the capital of Thailand, a country in South East Asia that borders Vietnam. Thailand has a very long and proud history, and it's one of the few countries in this part of the world to not be colonized. It is considered to be part of the developing world, which means that the country is growing fast, and that in some areas, like public health, there are still many problems. However, there is also much wealth in Bangkok, and it is a comfortable city by most standards.

The first weekend that I was here, I decided to join some friends from California on a trip to a national park. The park's named is Khao Sam Roi Yot, and it is located right on the coastline. When we arrived at the hotel, I went to swim, only to find hundreds of jellyfish floating through the water! After a few hours, during which we enjoyed fresh, spicy seafood, we got to the national park. Khao Sam Roi Yot means "mountain with 300 peaks." The landscape is beautiful, with limestone cliffs covered in dense green vegetation, which included some familiar plants, like palm trees and cactuses. The mountains there are limestone, and many years ago, the region was underwater. One of the most amazing things to see at the national park is the Phraya Nakhon Cave, which is a short walk from one of the park's main beaches. As my friends and I began our climb up to the cave mouth, it started to pour – really pour. Within a few minutes we were completely drenched. Luckily, it was also very warm, maybe 80 degrees Fahrenheit, so the water was enjoyable. Soon, we found the cave opening, a gaping cavern at least 40 feet high and maybe 60 wide. The cave has two main chambers, and both have large openings in the ceiling, so light streams down and plants can grow within. Looking up as the rain cascaded through the cave opening felt like standing inside of a waterfall. The main chamber of Phraya Nakhon Cave is special for the Thai people because it has been visited by many kings. Over 100 years ago, a small throne was built inside the cave. Constructed with traditional Thai aesthetics, it looks similar to a shrine or temple. The cave also has many stalactites, stalagmites, and columns. These are formed when water makes its way through rock and drips down to the floor. As it drips, calcite, a mineral substance in limestone, comes with it, and over thousands of years, a stalagmite forms on the ground. Limestone has these substances because it is made up of the skeletons of coral and other sea creatures, many of them millions of years old. |

Adam De GreeI am a senior in college, studying philosophy, and am visiting family in the Czech Republic and travelling and studying in Europe and Asia. Archives

January 2016

Categories

All

|

|

SUPPORT

|

RESOURCES

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed