|

It's crazy to think that I'm entering the final stretch of my time in Thailand. After several months of adventure and exploration, there are only 4 and a half weeks left of school. There's one big journey between me and finals: a trip to Myanmar, formerly known as Burma. I'm very excited for this journey, and history should be a big part of the experience.

Myanmar's two names speak to the nation's diverse heritage: over 100 different peoples live in the country. The largest group, the Bamar, gives the country one of its names. Myanmar has been populated for thousands of years, and a number of empires called the region home. The Burmese were once a dangerous force in Southeast Asia, and they destroyed one of Thailand's great kingdoms, Ayutthaya, several hundred years ago. In 1824, the British conquered and colonized the region. For the next 120 years, they ruled over Myanmar, despite the sometimes violent protests of local people. In 1948, after the horrors of World War II, Burma gained its independence. However, less than fifteen years later, the Burmese military staged a coup. For the next fifty years, democracy was virtually dead in Burma: generals ruled over all aspects of the society, and the country became one of the poorest in the world. In 1990, after years of protest and thousands of civilian deaths, the country held its first election. The National League for Democracy, lead by Nobel-Prize winning Aung San Suu Kyi, won 80% of the seats in Parliament. However, the military refused to turn power over, and ruled until 2011. In the last five years, the government has changed slightly, opening up space for more democratic processes. Yet, the generals have also developed a plan for 'disciplined democracy,' one that guarantees the military 25% of the seats in parliament, no matter what happens. This week, the country held elections and, once again, Aung San Suu Kyi's government won a large majority of seats. Time will tell how these events affect Myanmar's society. In the meantime, foreigners have been allowed to visit the country for the first time ever. I'm interested in seeing what this almost untouched land is like.

1 Comment

Over the past 8 weeks, I've been contributing to an organization that aids refugees as an intern. I've learned a lot on the job, which also includes a writing position. I've been researching and writing about different human rights issues in South East Asia. Most recently, my focus as been on land grabbing, which is when large companies, some of them government-owned, take land away from local people to start planting crops that they can sell to people all over the world, like rubber, which people use for tires. It's interesting to see how the things that people in the West buy affect the poor all over the world.

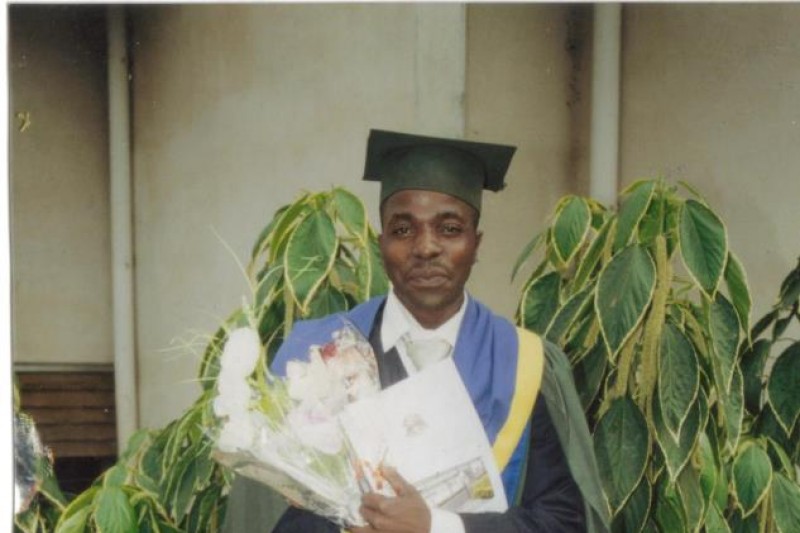

Another interesting issue that I've encountered has been the struggle for independence in Southern Cameroon. Cameroon has a complex colonial history; it was, at different points, controlled by British, French, and German powers. Thus, different parts of the country speak different languages, and at the end of colonialism, no one was entirely sure how Cameroon would be organized. The process of independence began in the 1950s, and in 1959, Southern Cameroons effected the first democratic transfer of power in 20th century Africa. Eventually, the UN gave the people who live in Cameroon several options, including unification with Nigeria or joining the French and English speaking parts of the country together into Cameroon. When the country was formed, the government of Cameroon was a federal government, composed of two states – one, the French-speaking 'La Republique du Cameroun,' and the other, 'Southern Cameroons.' For the first several years, these two states coexisted on equal terms, and, while they still experienced problems, they had a functioning democracy. However, in 1972, the leader of La Republique du Cameroun announced a 'unitary government,' in which South Cameroons could not keep its own legal traditions. Since then, people in South Cameroons have reported many abuses on the part of government officials, and they have few opportunities to change their nation, as many political parties are outlawed. Members of the Southern Cameroons National Council are regularly arrested for holding meetings, and some have been tortured and killed. Today, Southern Cameroon holds a place on the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organisation. I've been visiting a political refugee from Cameroon for some time now – he went through some horrible things in his home country when he spoke out against oppression. Meeting with him has been fascinating and inspiring, and also sad – I still know very little about Cameroon, and there must be many other places like it in the world.  Peter is a 28-year old political refugee from Cameroon. I met him while visiting Bangkok's Immigration Detention Center (read: prison), where asylum seekers, even those recognized by the United Nations, are detained for years at a time in inhumane conditions. In the IDC , inmates are literally stacked on top of each other in cells meant for 15 people (many house more than 100). They receive inadequate food, are forced to drink Thailand's tap water, and often suffer from debilitating diseases. Peter fled Cameroon, where he experienced oppression and torture as a result of his human rights activism (read here and here to learn more), in hopes of finding safety. Yet, thanks to Thailand's legal system, he's been stuck in IDC for over 8 months, and his health is suffering. He has already been hospitalized and lives in fear of contracting a major illness. The thin rice gruel that comprises breakfast, lunch, and dinner in the IDC leaves his immune system with little energy. Each time I speak with Peter, he talks of his hope, his faith, and the necessity of positivity. Like many of the inmates, Peter finds strength in the Bible, and others call him "the pastor," as he organizes Bible readings, prayer groups, and meditations for those inside. Getting to know him has been an eye-opening experience. Recently, Thailand's immigration department has allowed refugees to post a bail of 50,000 Thai Baht, which comes in at just under $1,400 USD. After posting bail, they are allowed to live and move freely within Thailand as they await relocation to a third country. Peter is confident that his health will improve once he is out of the detention center. Any amount that you can spare will bring him closer to freedom. Go here to learn more about donating. Questions? Email Adam at Adam's Email. One of the most interesting parts of studying abroad in a developing country is the discovery of different concepts of rights. Living in Thailand can be difficult at times simply because of the way that the government works; people here do not have many freedoms that I take for granted, such as speech, as their education system keeps them from criticizing their rulers. Right now, Thailand is under a military dictatorship, which means that generals are in charge of all of the decisions for the entire country. Ever since the military took over in 2014, there have been many human rights issues in this country, issues that affect everyone from students to refugees. Sadly enough, this isn't the first time that Thailand's government has failed to secure the rights of all people within its borders.

I study at Thammasat University, which has a proud tradition of political activism that stretches back to its founding in the 1930s. For many years, Thammasat was the place where demonstrations began, where people gathered to discuss the problems with their country, and where change happened. In 1973, students from many universities banded together at Thammasat to protest the rule of a military government that had held power for decades. The protests soon gained the approval of the public, and soon they included 500,000 people. Over the course of several days, the military killed about 100 students, but in the end, the military government resigned: Thailand was a democracy once again. However, just 3 years later, tensions from nearby Vietnam, which had just fallen to Communism, reached Bangkok. Members of the military wanted to take the power back, and started to call reformers 'Communists' in an effort to gain international support. Since students tend to be liberal, and in Thailand at the time, this meant being critical of the wealthy royal and military elite, they were seen as a threat. In October of 1976, police responded to a political cartoon by surrounding Thammasat University. On the morning of October 6, police and military units opened fire on students. Over the next few hours, they killed hundreds of students, hanging many. Others were beaten, tortured, and imprisoned. Meanwhile, the military took power once again – and the West looked away. Over the next few years, America sent Thailand tens of millions of dollars in military and economic aid. Today, many Thai history books don't teach kids about 1976. Over the last ten years, the government has put pressure on Thammasat University, hoping to change the sort of students that attend the school. As a result, it has fallen from its former spot as one of the nation's finest universities, and an increasing amount of students come from wealthy families, uninterested in changing their society. It's a complicated environment, one that changes as quickly as the weather in Bangkok. One of the most interesting things about Thailand is its government. Unlike many Western countries, Thailand has never been a full democracy. There is a long history of authoritarian rule here (authoritarian is when one person, or a group of people, have much more power than everyone else – they author the laws, and enforce them as well), and in the last few years, rising tensions between different groups of people have resulted in violence. Now, a military government has stepped in to stabilize the country, although many are worried that they will stay for much longer than is necessary. Just last week, Thailand's constitutional drafting committee rejected its own draft – the 20th try at a Thai constitution – and it'll be about two years before the next public election.

Here, if you criticize the King and Queen, even past kings and queens, you can get sent to prison for 20 or 30 years. Other restrictions on free speech make press coverage of certain issues dangerous. As a Westerner, I have my own views of these laws. But I've also had some interesting conversations with educated Thais who like it this way. "I prefer an authoritarian form of government," one of my schoolmates told me over dinner a few nights ago. "I think it's important for people to have an example to look up to, and in America, where you have all this freedom, people still just want more and more. So I don't think that's any better." My first thought at hearing this was, "Wow, your education system did a good job." The history that Thai students are taught in school is all about the greatness of Thailand's kings, and it tells students about all the ways in which they protected the nation from its evil neighbors. People learn, from an early age, that without the King and Queen, who they call "Dad and Mom," society would fall apart. My second thought was, "Wow, my education system did a good job." In America, our national history also tells a certain story. In schools, we pledge allegiance to the flag, and many of us are taught to associate America with virtue ("a shining city on a hill"). At the same time, our policies during the Cold War strengthened Thailand's military as the nation further restricted free speech, labeling any criticism of human rights abuses as "Bolshevik propaganda" and throwing people into jail - or worse. So while I believe that people deserve to have a say in the way that they're governed, it's difficult to say that my friend is wrong. She was just learning history. This weekend, I chose to stay in Bangkok, as I had a meeting for an internship I'm pursuing here. I won't talk about it too much now, but it includes visiting refugees from Pakistan, Cameroon, and Vietnam at a detention center, basically a prison, where many live for as much as 2 years without gaining an interview. The day after my meeting, I went to a historical park called Muang Boran, or The Ancient City. It's a massive complex, spanning 240 acres, and inside there are miniatures of monuments from throughout Thailand – in fact, the entire park is a to-scale model of the kingdom.

The monuments, while miniatures of the originals, were still huge, with many towering at least 50 feet high. Some of them housed beautiful artworks, mother-of-pearl thrones, and Buddha statues. A river ran through the entire park, complete with its own floating market. It was a surreal experience, made more so by the slight rain that showered down as my friend and I biked through the city. This experience brought up some interesting thoughts. Muang Boran was founded by a man who wanted to educate Thai people about their heritage. He thought that building a historic park that showcased the wonder of Thailand's monuments would inspire people with respect for their own culture. The park is also open to foreigners, and like many attractions in Thailand, it costs twice as much to go if you're not a local. The park took years to complete; the details on many of the buildings required the work of skilled craftsmen, and the architect, Lek Viriyaphant, visited many of the 116 monuments himself to ensure that the replicas were accurate, while experts from the National Museum helped as well. During my time at the park, I had lots of time to think about the importance of religious art. In Thailand, religious symbols are everywhere. Museums like Muang Boran are often filled with Buddha statues and other sacred objects. My question is, what makes something holy? Is a replica of a religious statue just as sacred as the original? Every Thai person that I've seen at a museum has reacted to the statues around them as if they were the originals: they often get down on their knees, light incense, and maintain silence. On the other hand, these statues are housed in a museum that's open to non-Buddhists, like me, who treat them like artwork. My friend Tessa said that objects like Buddha statues are important because of the intention with which they were built, and that she has more respect for the originals than a replica on display. I think I agree with her, but it's a tricky issue, especially since the locals seem to respect the object itself, regardless of the situation. I'm writing this travel log a bit behind schedule. Last Sunday, I hitch hiked from Prague to Germany. Hitch hiking is when you stand by the side of the road in a safe area (gas stations are also good places), and ask people if they can give you a ride. It was my first time hitch hiking, and it was an interesting experience. Lots of people in Europe and America used to hitch hike, but today, it is far less common. Many Europeans today are worried about immigration, and they are less likely to trust strangers. Still, there are many generous people around, and I made some new friends.

I eventually ended up camping in a forest outside of the German city of Dachau with three French students. We had many interesting conversations about life in Europe and America, and we talked about everything from religion to politics. During the day, we visited the concentration camp memorial site in Dachau. During World War II, Germany was led by a very powerful man named Hitler. Hitler was able to unite people all over the country, and he made them believe that they could rule the world. One of the ways that he united people, however, was by finding groups of people to hate. Hitler blamed many of Germany's problems on Jews, as well as homosexuals, communists, and others. During the war, German soldiers hunted down millions of innocent people and put them in concentration camps such as Dachau. At Dachau, tens of thousands of people were forced to spend all day working, in sun and in snow. Those who could not work were killed. Over the course of the war, huge numbers also caught terrible diseases, while others suffered as experimental subjects for German scientists. The guards at Dachau often went out of their way to make sure that life was miserable for the prisoners. By the end, over 40,000 people died at Dachau. People have found many ways to remember the things that happened at Dachau. Some have created art that expresses parts of their experience in the camp. The memorial site has a very impressive sculpture by the artist Nandor Gild that caught my eye. It is a very powerful work, and it fit the site well. At the base, there is a simple message: Never Again. |

Adam De GreeI am a senior in college, studying philosophy, and am visiting family in the Czech Republic and travelling and studying in Europe and Asia. Archives

January 2016

Categories

All

|

|

SUPPORT

|

RESOURCES

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed